It isn’t difficult to find anecdotal evidence of the benefits of cover crops in a cropping system. Researchers and on-farm trials are showing varied methods that work. But how do cover crops pencil out in the long run?

One northwest Cedar County farmer is trying to figure it out, at least on his own farm. At a recent cover crop meeting at the Jeff and Jolene Steffen farm, Jeff Steffen talked about critical elements that have helped him implement cover crops into his 25-year continuous no-till cropping system and to make them pay.

“The ground I farm had been tilled for 80 years,” Steffen said. “When I started farming it 30 years ago, I thought no-till was good enough. But after 20 years of no-tilling with corn and soybeans, I was disappointed that my organic matter wasn’t going up very fast.”

That’s where cover crops come in. After five years of cover crop experimentation, Steffen noted a few crucial components he had learned. He added a cereal grain, such oats, to his previous corn-and-soybean crop rotation.

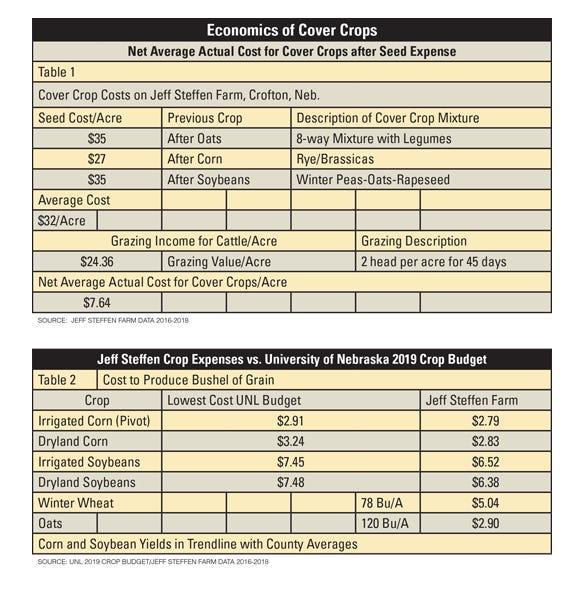

Steffen tries to plant cover crops early enough in the fall to get the biomass going. Plus, he grazes his cover crops and believes that gaining grazing value through livestock helps cover crops pay.

But the real cost advantage to a strong crop rotation that includes cover crops is in reducing the cost of his inputs. In fact, Steffen’s own numbers now reveal that since adding cover crops to the system, he is getting irrigated corn yields that are in trendline with the county average for his region with only 6 inches of irrigation water and only 0.59 pounds of applied nitrogen per bushel of corn produced.

“You need to have a living root in the soil in order to reduce applied nitrogen,” Steffen said. “And I cut back on my nitrogen slowly over time.”

“I’ve been able to go with all conventional soybeans now, saving on seed cost,” Steffen added. “I don’t have any insecticide or fungicide treatment costs, and I’m no-till so I don’t have extra fuel expenses.”

He didn’t cut these expenses from his cropping system overnight, but slowly gauged how these input costs interacted with his profits and yield potential, so he could ratchet the input expenses down year after year.

“High land costs around here hurt the idea of small grains like oats,” Steffen acknowledged.

But he noted that oats are a low-cost crop that can yield as high as 120 bushels or more per acre at test weights of 38 pounds or more per bushel in his area. By harvesting only the heads and leaving a tall stubble, along with spreading the oat straw in the field, he builds more organic matter.

The timing of small grain growth and harvest disrupts insect and disease cycles. With an earlier harvest, oats provide the cover crops with more time to build biomass and provide more grazing than with only corn and soybeans. That’s why corn crops following oats get a strong yield boost the following year, Steffen said.

The small grains help boost organic matter in a big way, Steffen explained.

“The problem with just corn and soybeans is that you can’t get enough carbon in the system to raise organic matter,” he said.

While the numbers don’t lie when it comes to profits, soil health benefits also are evident.

“By keeping things covered, we are able to reduce inputs, get as good or better yields and improve water infiltration and water-holding capacity in the soils,” Steffen said. “To truly build organic matter with cover crops, you really need to add that small grain to the rotation.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like