May 24, 2023

It can be easy to look at the rolling, lush expanse of a golf course and mentally tally the amount of fertilizer and water it takes to keep it well-manicured and ready for play. However, looking at the scale of different land uses in Iowa, golf courses and other urban and suburban uses such as lawns, sports fields and parks that are groomed and tended for aesthetic or commercial purposes represent a mere sliver when compared to the acres of cropland throughout the state.

Matt Helmers, an Iowa State University professor and director of the Iowa Nutrient Research Center, recently hit the books to work out the numbers and take a swing at quantifying the relative contributions of nitrate to the state’s waterways. While he made some assumptions in the process, he did so in ways that placed a higher burden on city and built-up, or commercialized, lands than on farmland.

Comparison

As an avid golfer, Helmers often has been out on the links, but he has also been in a lot of farm fields and regularly speaks with farmers and agricultural professionals about conservation practices aimed at reducing nitrate in Iowa’s water.

“At some recent farmer-landowner meetings that we hosted throughout the state, participants were asked to list the leading causes of water quality issues in Iowa,” Helmers said. “It was not a big surprise that many participants listed urban areas such as golf courses and lawns among the top three causes.”

The assertion that lush lawns are a major source of nitrate runoff has been common for many years, and there is a certain logic behind it. However, the enormous difference in acreage in crop production versus that of cities and built-up areas more than balances the scales. Helmers turned to data from different studies to work on the root of the nitrate problem.

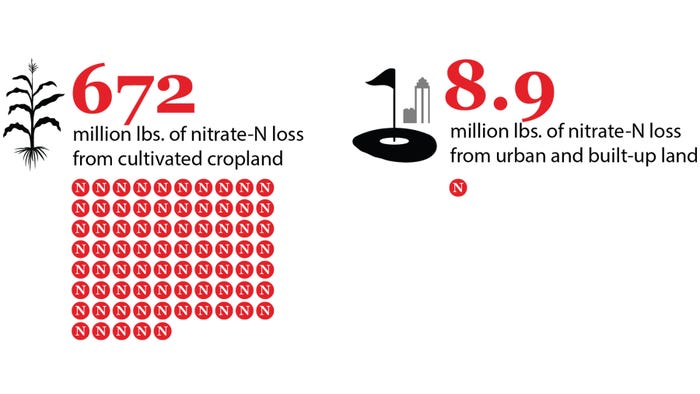

FARMING VS. GOLF COURSES: Farming takes up a larger portion of the nitrate use as compared to golf courses. (Courtesy of Iowa Learning Farms)

According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s National Resources Inventory (2017), there were about 24.9 million acres of cultivated cropland and slightly over 1 million acres of urban and built-up land in Iowa. This urban and built-up land includes residential, industrial, commercial and institutional land; construction sites; public administrative sites; railroad yards; cemeteries; airports; golf courses; sanitary landfills; sewage treatment plants; water-control structures and spillways; and highways, railroads, and other transportation facilities if they are surrounded by urban areas.

Nitrate numbers

Moving to the next stage of his analysis, Helmers looked at data enumerating measured nitrate-N loss and common application rates of nitrogen fertilizer.

Helmers cites a meta-analysis done by Bock and Easton (2020) of studies across the country, in which the researchers summarized that the median nitrate-N loss via leaching and runoff was 8.9 pounds per acre from turfgrass plot studies. In an Iowa-centric study, Schilling and Streeter (2018) monitored a number of golf courses in Iowa and estimated the mass of nitrate-N recharged to groundwater in golf courses to be about 3 pounds per acre. For comparison, Lawlor et al. (2007) reported an average annual nitrate-N loss of 27 pounds per acre from 15 years of a corn-soybean cropping system at a fertilization rate of 150 to 160 pounds of N per acre, which would be a common fertilization rate.

Taking a broad view of these collective studies, Helmers concluded, “While not all the urban and built-up land is in lawns or golf courses and not all these acres would lose the same amount of nitrate-N, if we multiply the 8.9-pound-per-acre loss by 1 million acres, we get 8.9 million pounds of nitrate-N loss from urban and built-up land. In comparison, if we have the 24.9 million acres at 27 pounds per acre lost — which again, I grant, is an average and approximate value — there would be 672 million pounds of nitrate-N loss from cultivated cropland.”

In returning to the original question of causes of water quality issues, Helmers was careful to reinforce that regardless of the huge difference in total acreage or contributions of nitrate, all landowners, farmers, homeowners and land users must work to decrease nitrate-N loss through appropriate nutrient management.

“Some people will feel better about playing golf without the concern that their recreation spot is contributing to substantial environmental damage,” Helmers said. “However, understanding where nitrate comes from, the magnitude of various contributors, how it gets into our water and what we all can do to mitigate losses are things everyone should strive for.”

For further reading, consider:

Bock, E.M., and Easton, Z.M. (2020). Export of nitrogen and phosphorus from golf courses: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 255. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109817. Visit pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31783211.

Schilling, K.E., and Streeter, M.T. (2018). Groundwater Nutrient Concentrations and Mass Loading Rates at Iowa Golf Courses. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 54(1), 211-224. doi:10.1111/1752-1688.12604. Visit onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1752-1688.12604.

Ripley is Iowa Learning Farms manager and a Water Rocks! conservation outreach specialist.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like