Chatter in the grain market over the past week focused on World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates for November, due out today. But while traders debate the potential for rising world surpluses of 2021 crops, USDA somewhat quietly released another report that could ultimately have just as much, if not more, impact on your farm’s financial health. The agency put out its first official forecasts for next year’s acreage, production, and prices that provided at least a few big surprises.

Early-Release Tables from USDA Agricultural Projections to 2031 dropped Friday as part of the government's budget process, which requires estimates for spending on farm programs over the next decade. While the out years of the outlook can largely be ignored, the forecast provides a look at how the debate over acreage could play out between corn and soybeans this winter.

These estimates used the October WASDE numbers for old crop ending stocks as a starting point, so they likely are already a bit dated depending on the update USDA puts out today. But they’re the only somewhat “official” forecasts the market will have until the baseline tables get a refresh in February, ahead of the annual prospective plantings report due out at the end of March.

Planting intentions mystery

Acreage likely is the headline numbers from the baseline, if only because farmers’ plans for the coming spring remain largely a mystery. USDA came well short of Farm Futures August grower survey, which found producers looking at 94.3 million acres of corn and 90.3 million acres of soybeans. USDA, using economic forecasting models, not surveys, put corn at 92 million, down 1.3 million from 2021, while soybean seedings would be around 265,000 acres higher at 87.5 million.

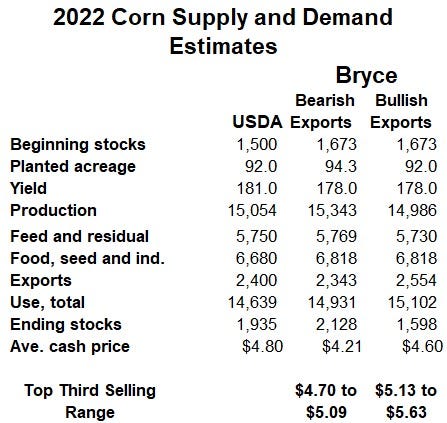

There are lots of ways to mix and match these acreage forecasts to produce price projections for the year ahead. I’ve prepared two versions of my models, one assuming USDA acres, the other using the Farm Futures survey. Not surprisingly, more acres would mean lower prices than the government tables. Here’s a look at the scenarios so far.

With production outstripping demand, USDA’s baseline would increase 2022 crop ending stocks to 1.935 billion, up from the 1.5 billion 2021 estimate printed in October, with the average cash price lowered to $4.80.

The first difference with my estimates comes from old crop carryout. I believe it will ultimately be higher, more like 1.673 million, depending on how production and demand play out. I also plugged in a lower “normal” yield for 2022. USDA assumes average growing season weather and planting speed in its yield forecast of 181 bushels per acre. I use a 20-year trend, or statistical yield, of 178 bpa.

Using USDA’s 92 million planted acres, my “bullish” table assumes a crop of around 15 billion. But usage would be stronger. USDA seems too low on its forecast for demand to make ethanol. If exports turn out stronger than the government’s projections, carryout could decrease slightly to 1.598 billion under this somewhat more bullish outlook. Still, I put the average cash price for the crop 20 cents below USDA at $4.60, because world stocks should continue to build, affecting U.S. domestic prices. The expected top one-third of the futures selling range would be $5.13 to $5.66. December 2022 corn futures peaked near the top of that range at $5.58 last week, and traded Monday about 20 cents lower than that.

Under the “bearish” version of events, the highs are in. Planted acreage of 94.3 million means a crop of 15.3 billion bushels, even using my slightly smaller yield. But under this outlook exports would falter, swelling carryout to 2.128 billion bushels, lowering the average cash price to $4.21. That translates into a projected selling range of just $4.70 to $5.09, where the market was trading when the Farm Futures survey was conducted last summer.

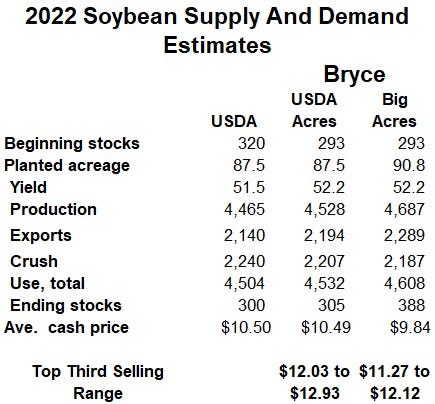

For soybeans, USDA said ending stocks would actually decline slightly, from the 320 million 2021 crop ending stocks forecast in October, to 300 million at the end the 2022 crop marketing year. The average price for the year would be down to $10.50, still a profitable price for most producers.

Unlike corn, my statistical yield of 52.2 bpa for beans would be higher than the government’s 51.5 bpa. But with USDA’s 87.5 million planted acres, my forecast for this scenario sees better demand offsetting increased production, taking ending stocks only 5 million higher than the government at 305 million. My average price forecast for the crop would be virtually the same, creating a projected selling range of $12.03 to $12.93. November 2022 futures peaked at $13.1375 in June, but are now struggling to stay above $12.

Current new crop prices suggest the market is leaning towards the larger acreage found in the Farm Futures survey. Using 90.8 million planted acres, normal yields would mean a larger crop, but that could increase export demand with lower prices. Under this take, ending stocks would rise to 388 million, putting the average cash price for the crop at $9.84 and lowering the top third of the selling range to $11.27 to $12.12, suggesting plenty of downside.

Just a start

Questions abound in any discussion of 2022 prices. Fertilizer prices went up again last week – the average cost for feeding an acre of corn moved to $207, while soybean nutrients are at $85. Nonetheless corn retained a strong profit advantage to soybeans at current futures prices, assuming growers can find the inputs they need to put in the crop.

Projected profits do influence farmer planting choices, though weather and other factors make predictions hard to make six months before planters will be flying flat out around the Corn Belt. Farmers shifted huge amounts of corn ground to soybeans in 2008, but record fertilizer costs were only part of the story. Corn penciled out more profits than corn in the winter of 2008 but soybeans were nearly as good, making it easier for growers to switch.

Export demand in part hinges on the choices other farmers make around the world, and how their weather affects yields. A global economy healing from the pandemic would be positive, but politics with Russia and China could play a role too. The strengthening grip of the Communist Party on Chinese society could discourage imports of both corn and soybeans from the U.S. Russia’s grain crop could be important as well, and that country last week announced restrictions on fertilizer exports that threatened to tighten the supply chain even more.

The good news? Every farm’s economics are different, but the choices you make for your operation in coming weeks and months should teach you plenty about what other growers will be doing around the world.

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like