The U.S. economy is proving tougher than we all imagined about a year ago, and that’s good news for all.

“Covid caused one of the biggest economic collapses the U.S. has ever witnessed --the largest decline we have experienced since the great depression,” sums up Purdue economist Jason Henderson.

According to the Federal Reserve, 2020 GDP ended up minus 2.2% to minus 2.5%. The economy rebounded last summer and now economists expect positive growth of 3.5% to 5% in 2021, despite major headwinds. The Fed expects 3% to 3.5% GDP in 2022 and incrementally smaller growth over the next three to five years.

“We’re on the road to recovery, but it will be slow and steady,” Henderson says.

Government stimulus packages proved the difference in turning negative forecasts to positive. That’s true elsewhere as well - China had been forecasting 1.0% growth in June and now expects 2.3% growth based on a December 2020 International Monetary Fund forecast released in January.

“Less negative is always a positive, and China and the U.S. do things differently,” he says. “In the U.S. they’re looking at individual payments per person and in China the spending is on infrastructure investments.”

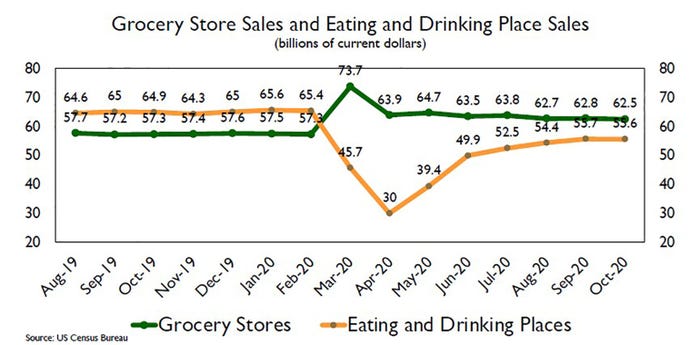

What does the rebound mean for farmers? Covid-related restaurant losses of $10 billion per month are partly offset by grocery store gains of $5 billion per month, and grocery store prices increased. Shortages and supply chain issues, especially in meat packing, seem to be ironed out.

“The consumer is spending almost the same amount of money as before, but it’s going toward grocery stores instead of restaurants,” he says.

Recovery will be driven by government spending but also monetary policy. Interest rates are one of those drivers to watch. In an online poll most Fed attendees believed interest rates for farm real estate loans five years from now would be 5% to 7%; rates are currently at 4.2%.

Inflation worries

With so much government ad hoc spending the question everyone wonders about is how much money the Federal Reserve will pump into the economy. When will they stop the printing press?

Heading into 2019, the Fed had started shrinking its balance sheet, but with the recession spending increased dramatically. What are they buying? During the Great Recession it was mortgage-backed securities; now most of it is treasury purchases.

“The federal government is spending money on transfer payments and turning around and selling treasury reserves,” Henderson explains. “The challenge is we have a lot of money pumping into the economy in the U.S. and China, European Union. There’s a lot of money floating around.

“A trillion here, a trillion there, pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

They see low inflation over the next several years and for unemployment to ease over time.

In other words, getting back to normal will take some time. But that low inflation forecast comes with some caveats.

“Inflation emerges when U.S. GDP outstrips its potential GDP growth,” Henderson says. “It’s a measure of capacity. Until real GDP reaches the capacity for growth in our economy we won’t see that inflation take place. It’s going to take a couple of years.”

When interest rates start to rise, you get acceleration - a snowball effect on U.S. debt and that can get out of control fast, says Henderson. So you have to limit inflation and interest rates, higher taxes and lower spending. Think about how large the Fed’s balance sheet is now; when interest rates rise it puts strains on that balance sheet. How will we make that work going forward without taking additional money from the federal government?

COVID risk

The biggest risk to recovery, of course is still COVID-19. While vaccines have – finally – started to move into needles and arms, there’s still a risk COVID could clip this recovery. Watch for these fundamentals:

On manufacturing new orders are growing faster; production, order backlogs are growing faster; employment is growing – but customer inventories are too low. “’Just in time’ is ‘just too late,’” in many cases, says Henderson.

Service is the biggest at-risk sector. New orders and production are growing but the backlog of orders is contracting as is employment, even as inventories are now growing. Henderson says that’s a sign sales are disappointing, and that’s a risk to recovery. It could trickle back to the manufacturing sector.

State and local governments account for 12% of U.S. employment. Personal income taxes fell less than expected during pandemic. Capital gains tax revenues held up with surging stock markets. Property tax revenues held up with high home and land prices.

“Depending on where you live, if your state is heavily dependent on sales and consumption taxes from revenue streams, you‘re going to have a big challenge,” says Henderson. “Not so much if your state depends on property taxes.”

Debt and recovery

Both personal and government debt is a risk to recovery. Households have done a good job bringing down debt after the great recession. In 2007 it was at a high at 13.2% of disposable personal income; that number has plummeted to less than 9% in 2020.

Federal government spending is a different animal. Last year the federal government debt-to-GDP was at a record high of 135.6% but dipped to 127% by third quarter 2020. In short term federal debt needs to be high to get through COVID, but afterwards, “we’re going to seriously have to address what debt levels should be going forward,” says Henderson. “In my opinion it should be shrinking. We’re the best-looking house on a bad block.”

But how to shrink federal debt? Higher taxes, or shrink government benefit programs?

“The reality is we’re probably going to have both higher taxes and reduced benefits,” he says. “We could put our heads in the sand and let our kids handle it; that’s what has been happening now.”

How will the U.S. manage debt post COVID, with so much political polarization? Democrats and Republicans have to work together. It’s simple to say and write, but that’s where simple ends.

What farmers should look for

Farmers should watch monetary policy. Farmers are usually asset rich and cash poor. Low interest rates reinforce asset values and reduce debt service.

Watch also trade policy. There are new rules coming in the game of trade.

Last, watch farm policy. Will it offset recent bad trade outcomes for agriculture?

Volatility is low now, but it shifts on a dime. Think about how you will manage risk in a rising interest rate environment. Interest rates have, in effect, nowhere to go but up.

Think about technology and the lasting impacts of COVID. How will supply chains shift? Should you strategically work to become a local or regional niche or high value supplier? Consumer trends will impact food, ag and energy.

Why the stock market is at record highs in a recession

At the end of 2020 both the S&P 500 and stock P/E (price-to-earnings) ratio were rising at the same rates. If prices are rising with earnings your P/E ratio is flat. Right now, S&P prices are rising, P/E ratio is rising at same rate, so prices are rising faster than earnings. P/E ratio is over 35.

In the stock market, when P/E ratio is above 30, it gets into bubble territory.

What’s driving that?

Low interest rates for starters. More importantly P/E is rising because the U.S. is the world’s safe haven for investments. More foreign money is coming into the U.S. than U.S. money going out.

On net, $13.5 trillion in international investment was flowing into the U.S. in the third quarter of 2020.

Even if your assets are not in the stock market and mostly tied up in farmland, it does matter. Farmland is an asset in competition with other investment options.

Food for thought: As the world re-lives the awful events of Jan. 6 and the second impeachment of a former president, will it continue to trust us with their money? Will the U.S. always enjoy ‘flight to safety’ status?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like