June 17, 2022

Our newest invasive pest is the spotted lanternfly, which has now been detected in many eastern and northeastern states, and more recently, as close as Indiana. The Missouri Department of Ag has asked grape growers in that state to scout and report any findings, because of how quickly the spotted lanternfly can decimate a vineyard.

The spotted lanternfly is a unique spotted bug that feeds on grapevines and fruit trees. It was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014. The insect is native to China and is considered highly invasive, because it can feed on more than 70 plant species and has no natural enemies.

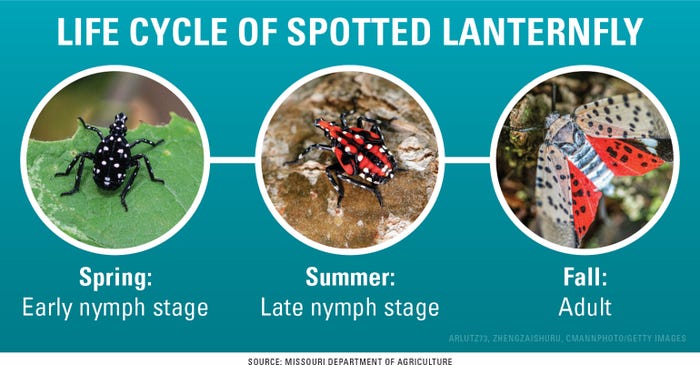

Spotted lanternflies feed on a variety of plants during June and into early July. The nymphs, which are wingless and black initially, develop red patches as they mature, and have white spots on their body and legs. Upon completion of their final molt, adult spotted lanternflies will begin appearing usually in early to mid-July and will be active into early fall.

They are 1 inch long and a half-inch wide with black legs and head, yellow abdomen, and light brown to gray forewings. The hind wings are scarlet red with black spots.

Look for adults on tree trunks and stems, and near leaf litter at the base of trees. Adults are poor flyers but strong jumpers. They favor tree of heaven, black walnut and grapevine as host plants. Adult females tend to lay eggs on smooth-trunked trees or any vertical smooth natural or man-made surface. They lay egg masses on trucks, train cars, RVs, etc., and can easily travel to new locations.

Heavy feeding may lead to plant stress and death. Sooty mold typically develops in association with honeydew, diminishing the plant’s ability to produce food. The spotted lanternfly has the potential to greatly impact the grape, orchard, logging, tree and wood-products, and green industries.

Spotted lanternfly females will begin laying egg masses in September and continue through November, with 30 to 50 eggs in a mass, which are gray-brown and covered with a shiny, gray, waxy covering that looks like a patch of mud. The eggs overwinter until the following spring, when they hatch. The young nymphs disperse and begin feeding on a wide range of hosts, producing large amounts of honeydew.

Miller is a horticulture professor at Joliet Junior College in Joliet, Ill., and a senior research scientist in entomology at The Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Ill. Email your tree questions to him at [email protected]. The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like