The Year of the Tiger was supposed to be a big one in China, with traditionally long Lunar New Year celebrations coinciding with the Beijing Winter Olympics. But the COVID pandemic upended plans for both events, leaving traders wondering if the fallout could dampen enthusiasm for U.S. soybeans as well.

While Feb. 1 is the first day of the Lunar New Year, the unofficial holiday period typically lasts a month, as millions of Chinese begin migrating home to their families two weeks before. Markets close for a week starting on Lunar New Year’s Eve and activity can be slow for an additional week as travelers return. This is a pause when news about soybean bookings can be sparse.

There’s uncertainty even in normal times about whether buyers will step back in for new purchases – or begin cancelling previous deals – when the long holiday is over. This year, pandemic upheavals and weather issues in South America create even more questions about the fate of U.S. sales to its biggest customer.

History provides a few clues, but no definite answers.

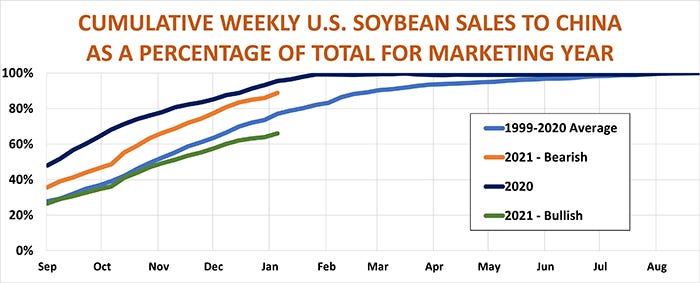

On average, sales after the holiday pick up, but a couple years when Chinese buyers made large purchases distort that number. Otherwise, sales went down 85% of the time since 1999.

Another fact making forecasts difficult: Some years the post-New-Year pattern affects total purchases from the U.S., while other years it doesn’t.

Indeed, a slackening pace after Lunar New Year fireworks isn’t necessarily bad for business. In years of post-holiday slowdowns, total U.S. sales to China for the entire marketing year tended to increase more because strong demand front-loaded purchases early in the selling season.

Business boomed last year

So what’s in store for the Year of the Tiger?

USDA forecasts total Chinese imports of 2021 crop soybeans will grow only minimally but doesn’t make estimates of how much of the total will come from the U.S. It’s possible, however, to make an educated guess.

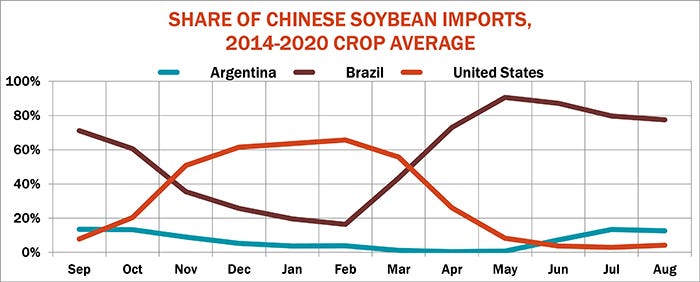

U.S. sales tend to reflect how our supplies of exportable soybeans, those that won’t be crushed or otherwise consumed domestically, compare to available stocks in Brazil and Argentina.

The La Nina drought a year ago trimmed yields in Argentina, the world’s largest exporter of soy products. There were other factors afoot too. Brazil harvested another record crop, but its sales were hurt by heavy U.S. bookings as China tried to fulfill promises under the Phase One deal that ended the 2018-2019 trade war.

Strong 2020 U.S. production, coupled with still-large leftover supplies from the trade war, gave the U.S. plenty of soybeans to sell in the marketing year, lifting its share of Chinese business to a near-record 1.3 billion bushels.

Based on these historical trends, U.S. sales to China could rise to 1.4 billion bushels if damage to crops in Argentina and southern Brazil during the second year of La Nina is as bad as some models show. While rains last week helped parched crops for now, losses may already be baked into South American yields.

Slow start to buying season

Still, for the bullish scenario to play out, Chinese imports must pick up considerably. China’s total soybean imports fell 17% year-on-year during the first four months of the 2021 marketing year. U.S. shipments to China are running even further behind, down 28% from last year, while unshipped sales on the books are off 22%.

A surge in business for the rest of the marketing year would buck the normal seasonal pattern. Most of China’s purchases from the U.S. are usually on the books by the time the Brazilian harvest gets underway after the first of the year. By mid-January, China normally has already bought 77% of its total for the year on average. The 2021 marketing campaign is way ahead of that pace. Currently, cumulative sales of 915 million bushels could account for 89% of total Chinese imports from the U.S. if USDA’s current production forecasts for South America hold.

Does China need more?

Some of the slow pace of total sales is due to non-demand factors, including shipping delays caused by Hurricane Ida and port congestion exacerbated by the pandemic.

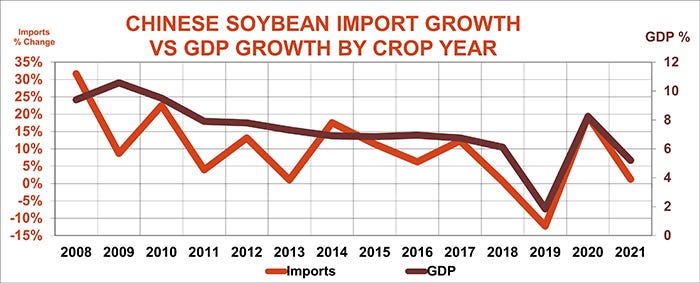

Nonetheless, questions persist about China’s need to import soybeans this year. Before the trade war disruptions, soybean demand reflected the pace of economic growth. China’s GDP growth slowed to less than 2% in the wake of the trade dispute and the onset of the pandemic, then rebounded to a strong 8.3% increase in 2021. But GDP growth could slow to 5.2% this year. Among the headwinds include the lingering effects of COVID lockdowns, an aging population, and government attempts to pivot the economy from exports to domestic consumption despite fallout from a troubled housing sector.

China may also continue to pressure its farmers to reduce consumption of soybean meal, even as its hog herd grows slowly, remaining 15% below levels seen in the boom years. Processors may be reluctant to push imports, too, because their crush margins are in the red. As a result, Chinese buyers may be willing to roll the dice on a good Brazilian crop and increased seedings in the U.S. to refill the export pipeline.

Of course, before even thinking about increasing export totals, China must take delivery of sales already on the books. If some of those outstanding sales are already hedges against a bad crop in Brazil, deals could be cancelled or rolled to 2022 crop delivery this fall. Coming weeks should prove whether China’s slow start to buying was a wise bet, or a bigtime mistake.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

Read more about:

ChinaAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like