A seasonal tendency is a predictable pattern in a time series that repeats over a one-year period. Because of the growing season, cash grain prices display a distinct seasonal pattern that reflects the production cycle. Let’s focus on corn prices. Cash corn prices are lowest at harvest and highest in the spring. Every year, harvest brings a large new crop seeking limited storage space, which pushes cash prices lower. In the spring, rivers and lakes open for business, which is generally good for demand. Also in the spring, producers start planting a new crop. Planting season can create an artificial shortage of grain, as busy producers are less apt to sell grain when planting is foremost on their mind.

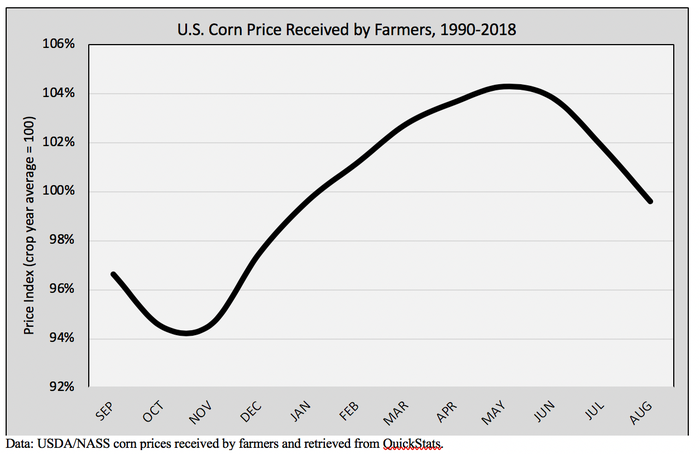

Seasonality in cash corn prices

Cash corn prices show a strong seasonal price pattern. Since 1990, the cash price of corn in May exceeded the previous October in 24 of 29 years, or 83% of the time. By the way, a cash price is made up of two basic components – the futures price and basis. You might be surprised to learn that the seasonal pattern displayed in this chart is almost entirely driven by a narrowing basis from harvest to late spring.

I should note that this pattern has been remarkably consistent through the decades. A chart of corn price patterns from the 1950s, 60s, 70s and/or 1980s would look very similar to the chart shown here. The production cycle has not changed!

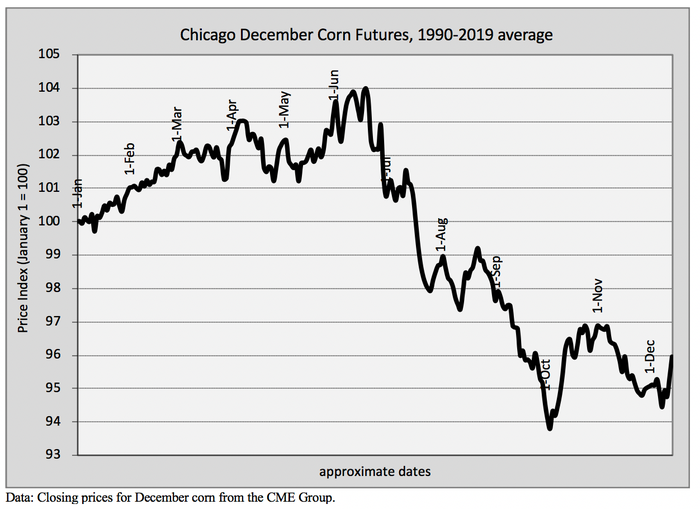

Seasonality in new crop corn futures prices

There is also a well-established seasonal pattern in new crop (December) corn futures. Prices tend to trade lower from planting (spring) to harvest (fall). Since 1990, December corn futures on October 1 were less than the previous May 1 price in 22 of 30 years, or 73% of the time.

Let me explain this tendency for higher new crop prices in the spring. Crop production is unique and important. In North America, it’s unique because we get one chance each year to get a new crop planted. Important because food and feed is vital to our survival.

This unique and important status translates into an anxious market during each planting season. This year the temperature is too hot (or too cold). That year the soil was too wet (or too dry). Still another year our planting progress was too early (or too late). The “too-too” season is a time of anxiety that manifests itself into higher prices in the spring.

Then again, a better explanation may be as simple as the natural tendency for grain futures prices to display positive carrying charges (like the December contract trading at a premium to the May and July contracts in the spring). Carrying charges often erode over time – deferred contracts seek the lower price level vacated by the expiring nearby contract. I suspect that both of these factors contribute to higher new crop futures in late spring.

Seasonal patterns in corn prices are the strongest of all grains, but they also apply to soybeans and wheat. And always keep in mind that seasonal patterns are tendencies, not certainties.

What can we learn from seasonal patterns in grain? From a pricing standpoint, spring and early summer is a time when grain producers should be alert.

Spring will be here soon. It’s time to pay attention to pricing opportunities in old crop and new crop grain.

Edward Usset is a Grain Market Economist at the University of Minnesota, and author of the book “Grain Marketing is Simple (it’s just not easy).” You can reach him at [email protected].

Read the other articles in the Advanced Marketing Class series:

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like