Memorial Day marks the traditional start of summer. But corn growers, and their markets, don’t get a vacation from weather worries that can make or break a crop.

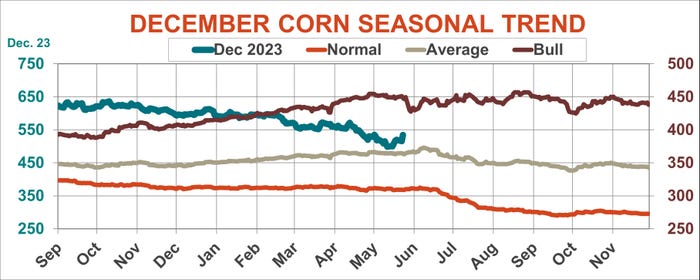

Holidays often seem to be turning points, and the observance that began as Decoration Day in 1868 fits the bill for corn. Over the past 50 years, December futures on average made a bottom for May around the parades and cookouts.

This year that low came earlier in the month on May 18, when new crop plunged on fast planting and concerns about demand to its lowest point since December 2021 before reversing higher. That kicked off a rebound of 50 cents by the time the closing bell sounded ahead of the three-day weekend.

Weather is again on the market’s radar because of what’s not showing up on the screen: rain. Soils dried out during the month due to below average precipitation across the growing region, coupled with warmer than normal temperatures except in the eastern Corn Belt. Last week’s Drought Monitor noted expanding dryness from the lower Missouri Valley into the lower Great Lakes and forecasts also sounded alarms. American and European weather models differ on some of the fine points but both see well below normal rainfall and above normal temperatures for the beginning of June.

Get ready for noise

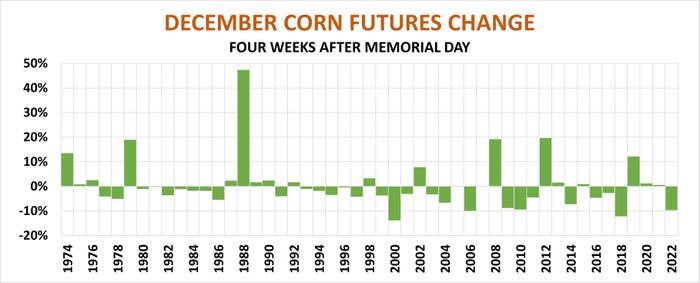

History shows these early weather rallies don’t last – except when they do.

December corn trading in June can be many things, but don’t count on quiet. In the four weeks after Memorial Day from 1974 to 2022 price moves of 5% or more happened one in every three years. And the frequency of these swings is increasing. Moves of 5% or more were seen in 10 of the last 15 years.

Memorial Day proved a bottom in many of the up years. On average the summer peak comes in just the second week of June.

What happened when markets reopened at 7 p.m. CT Monday isn’t necessarily a good guide for how the next four weeks play out. In 2008 and 2012 prices closed lower on the day after the holiday, before surging to rise more than a dollar a bushel.

A better guide is to track the change one week after the holiday. If futures are still higher there’s a very strong probability that prices will be higher four weeks after, when forecasts peer into the window for pollination.

Now or never?

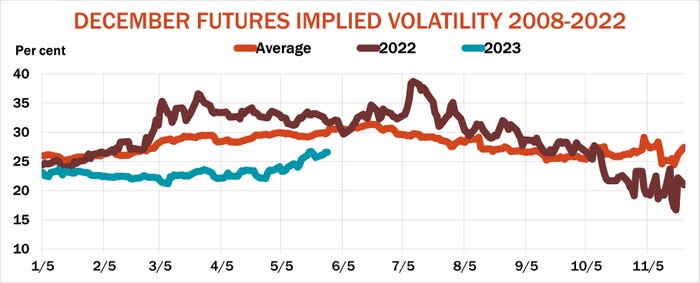

The uncertainty in summer markets is what makes pricing crops so difficult as the temperatures rise. And this year’s risk is more than usual. Evidence comes from implied volatility, a measure of uncertainty expressed in options trading.

Those who sell options to open the positions, also known as writing an option, require more premium from buyers upfront when uncertainty rises because they face greater potential to lose money on the trade. Those who sell call options could lose big if prices rise far enough, fast enough – exactly what happens in summer weather markets.

Implied volatility in December corn options rose steadily in May, beginning its seasonal move higher a bit earlier than normal. Typically, volatility rises in June on weather. But this year’s May jump came due to falling prices. Sellers of puts faced losses, forcing them to pay more as they bought their way out of the trade, liquidating more than 3,300 December $5 puts.

Time for insurance?

Options are often described as insurance, in this case, on prices. Growers who have already priced new crop may want protection against missing out on a summer rally. Or, they may fear futures hedges that lose money or not being able to fill forward contracts if yields plunge.

Others may want to own call options to make it easier to sell when emotions rise. If prices rise too, the calls could increase in value, resulting in a higher net selling price.

Just as you can’t buy insurance when your barn is on fire, options become prohibitively expensive if 2023 turns out like 2012 or 1988. So, with the weather clock already ticking, Memorial Day can the last chance to pick up calls “just in case.”

The end of May isn’t the best time to buy calls if you’re looking for bargains. Higher implied volatility means they’re likely to be more expensive than at the end of February or in April. My study of seasonal selling strategies shows these last-chance options tend to lose more money than calls bought earlier, resulting in a lower net selling price for those who combine them with futures or cash contracts.

But while straight futures hedges can lose $300 or more an acre in a year like 2012, owning calls cuts the risk by as much as 75%, and positions with the late May calls tend to lose even less.

Whatever your strategy, it’s time to get ready for summer and the marketing opportunities it brings. Buckle up because it’s often a bumpy ride.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected].

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like