USDA’s Feb. 8 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates weren’t expected to produce a whole lot of news and the government report didn’t disappoint on that count. But even the modest changes made to the numbers illustrate winter headwinds facing corn and soybean markets as they try to mount a spring rally.

For the record: USDA raised its forecast of ending stocks of both crops due to slightly weaker demand prospects. Corn usage to make ethanol dropped 25 million bushels, a cut that went through to the bottom line of carryout, which went up to 1.267 billion bushels. Soybean crush also went down, dropping 15 million bushels, raising the projected surplus at the end of the marketing year Aug. 31 by a like amount to 225 million bushels.

Markets traded the bearish numbers briefly, then returned to focus on South American weather and jitters on Wall Street. The fact the dust settled so quickly illustrates the difficulty grain markets have towards the end of winter: The news from USDA focused solely on the “old” crop from 2022. Once harvest is done, questions about supply are largely settled, leaving demand the only game in town, at least for now.

The market’s attention, which is notoriously short-lived, will soon turn to new crop ideas, a process that begins when updated forecasts for 2023 are released at USDA’s outlook conference Feb. 23-24. Those projections include acreage predictions made strictly on the basis of economic models, but pave the way for angst headed into release of the agency’s first survey of farmer planting intentions March 31.

Whether a “battle for acres” heats up enough to take old crop along for the ride remains to be seen. Until then, those who trade on fundamentals aren’t likely to see seismic changes.

Two categories – domestic processing and exports – should drive whatever debate there is.

Ethanol usage suffers

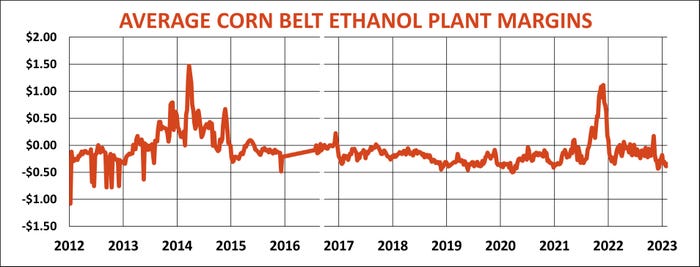

For corn, both areas are on the back foot. USDA’s decision to lower its forecast of how much corn will be used by ethanol plants was not the first, and may not be the last. The first forecast in May 2022 started off at 5.375 billion bushels, in line with its estimate at the time of 2021 crop usage. Cuts were made in September and October as it became clear rising gasoline prices were eating into demand at the pump, reducing the need for ethanol to blend. Good ethanol prices offset higher corn prices, lifting processor margins to the best level since 2014. Ethanol values are lower now, thanks to a pullback in by petroleum, and processors have little incentive to make more biofuel because corn prices stayed relatively strong.

Half empty or half full?

USDA made no change to its forecast for total corn exports, keeping them at 1.925 billion bushels – down 546 million from the previous year’s robust performance. Disappointing yields and acreage cuts produced a smaller crop in 2022 and fewer bushels means less to sell on international markets.

Prospects for that to turn around depend largely on what happens to fields in South America. USDA lowered its forecast for Argentine production by nearly 200 million bushels due to severe drought. Local sources see an even smaller crop, fears supported by Vegetation Health Index maps.

Weather in Brazil has been better for first crop production, but much of the country’s output comes from second crop “safrinha” planted after soybeans. Rain over the past week and forecasts for more raise concerns about delays that could cut acreage or put fields more at risk from dry weather ahead of harvest that normally begins in June.

A smaller Brazil crop could give the U.S. a leg up on sales to China, which are down 64% from the previous year as the world’s largest country tries to restrain imports and fill more of its needs from Brazil, which is selling corn there after finally winning approvals from the Communist government.

So, exports could get stronger, after a slow start, especially for shipments. A gloomy outlook for South America might boost U.S. sales by 100 million to 125 million, but that’s probably a best-case scenario for the U.S.

It might be enough to break nearby futures out of their months-long trading range, especially if farmers don’t boost acreage as expected. That could open the door to $7+ corn – but such heavy lifting depends on a lot of ifs.

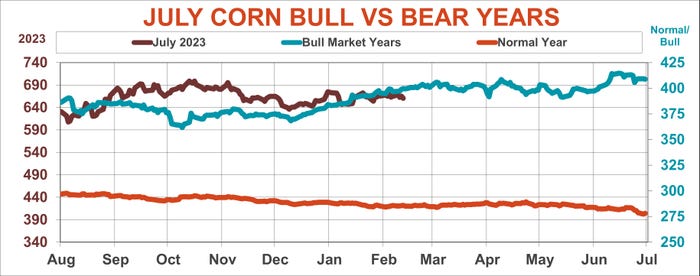

So far, futures reflect this uncertainty. The July contract made new lows in December, which it doesn’t normally do in bullish years with rising prices into spring. Still, futures did hold those lows in January, which isn’t typical for non-bull years. The glass could be half empty, or half full.

Crush is key

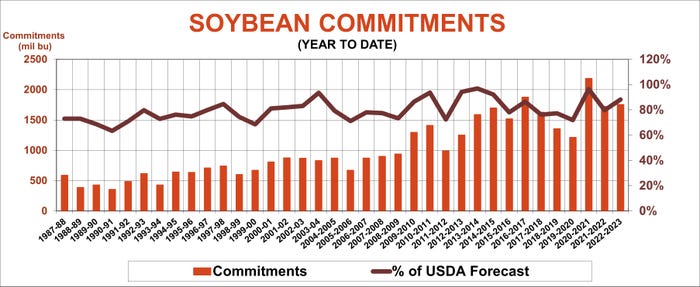

Rains are delaying Brazil’s soybean harvest, but likely won’t reduce production enough to make a significant difference. Argentina’s crop could be even smaller than reported by USDA, which cut its forecast by 165 million bushels. That could lift U.S. exports 15 million bushels above the 1.99 billion printed by USDA Feb. 8. Doing more business than that may take a resurgence in purchases by China,

U.S. year-to-date sales and shipments to China are up 15% so far as it reopens from COVID lockdowns, which caused its total imports to decline 8.2% last year. The U.S. share of the China market lagged its average pace through December, but appears to be gaining traction. Total U.S. sales and shipments to all customers are actually 23 million bushel higher than a year ago, though shipments still trail by 49 million bushels.

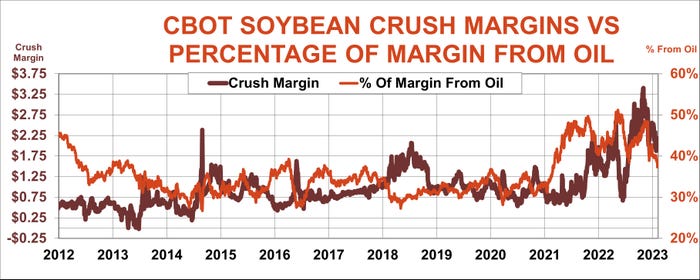

While the export outlook appears to be improving modestly, demand from processors also could be a concern. Crush tallied by the Census Bureau for the first four months of the marketing year was 1.1% behind 2021-2022 – a peak at data for January comes out Feb. 15 from the National Oilseed Processors Association.

Margins are double the average from the past decade but are down more than a dollar from records set last year, when lower production of oilseeds around the world and the Ukraine war caused soybean oil futures to surge to an all-time high.

Normally, soybean meal drives processor profits, but soybean oil took over the reins in 2021, eventually accounting for a record 51% of margins at last year’s peak. As soybean oil prices retreated, so did margins.

Bean oil’s future this year could depend on increased crush capacity spurred by hopes for another biodiesel boom. If crush doesn’t improve, the current pace suggests USDA’s estimate may be up to 50 million bushels too high.

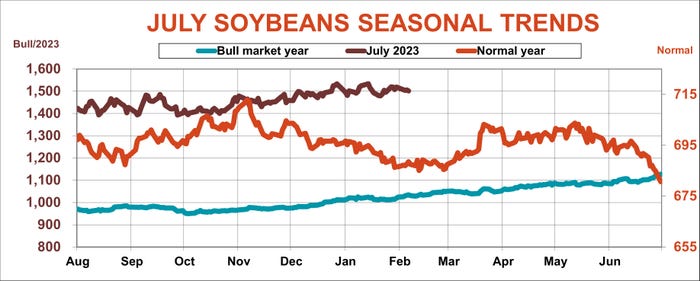

The seasonal chart for July soybeans shows a pattern of monthly higher highs and higher lows since harvest, the path followed in bullish years of rising prices into spring and early summer. If the trend continues in February it could be a set up for more gains.

Of course, those hopes could burst like a bubble – or a Chinese spy balloon, a reminder that volatility markets still have some bite left in them.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like