In January we asked readers to weigh in on organic production in our thrice-annual survey. You told us you hated it, in about 100 different ways. But more on that later.

Why would we ask such a dumb question in the first place?

In the past seven years demand for organic food surged while commodities mainly treaded water. In that time period if you had organic corn and figured out how to manage the weeds, you were laughing all the way to the bank. And only 30% of organic crops used in the U.S. are grown here in the states.

Today’s bull market made our organic queries somewhat outdated. Commodity crops are profitable again, and it’s a great time to be growing them.

Even so, organic demand continues to grow. And it’s a good bet it will continue to grow even after the bull market crashes from the weight of oversupply some time in the next two years.

Based on our January survey only 2% of respondents grow organic crops. Just one percent are making the transition to organic, while 2% say they tried organics, then quit. And 96% of you have never grown crops organically.

And based on the tone of the comments, never plan to.

It’s the weeds, dummy

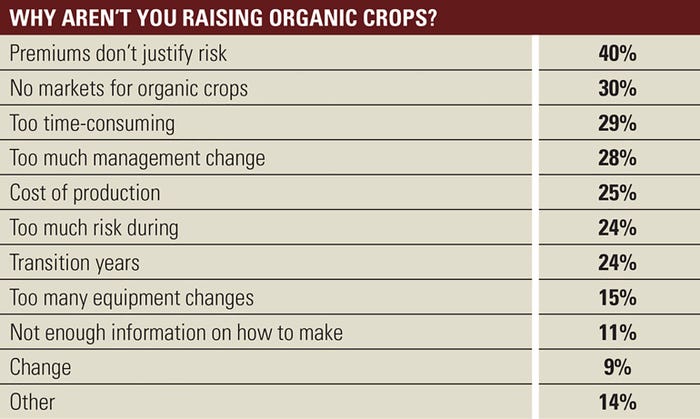

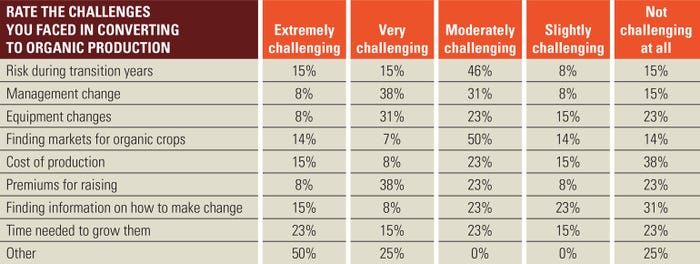

Respondents told us why they wouldn’t bother with organics (see tables). Based on the comments, weed control is by far the biggest challenge. Does it mean they just don’t want to switch from chemicals to cultivators or mini flamethrowers? Organic farmers I know use precision farming GPS to bury weed seeds between rows even before the crop emerges.

This could also be all about peer pressure, a real thing in farm country where everyone can observe your work from their windshield. No one wants to be ‘that guy’ with weedy fields, even if those fields eventually net more profit than chem-laden fields.

“It’s great if you like to look at weeds,” wrote one respondent. “I avoid organic as if it were poison,” another said. (That’s kind of funny considering the whole point of organic is to NOT put chemicals on your fields. But, I digress.)

When we asked, “Why aren’t you raising organic crops?” some of your reactions were priceless. “I’m old and uninterested,” wrote one farmer. “It's bogus,” wrote another. “I grew up on a farm in the 50's and would never go back to that lifestyle.” In fact, several farmers said age was the main reason they rejected this enterprise, along with poor yields and ineffective weed control. A lot of folks said, “I don’t believe in it,” which again made me wonder: shouldn’t you grow what consumers demand even if you think it’s stupid?

At odds with climate, soil health?

At odds with climate, soil health?

Despite some fun comments this survey really made me think about the disconnect between growing and eating organic. Organic production doesn’t fit the escalating soil health/climate mitigation agenda, which is quickly becoming this decade’s zeitgeist.

We’re seeing more and more efforts to get farmers to convert to climate-smart practices like no-till. But is tillage good for soil health? No. And many of our organic naysayers rightly noted that organic does not work well with no-till. Glyphosate is wildly popular because it controls weeds in no-till. That’s not a debate.

“Organic production is not responsible environmental management,” wrote one of our respondents.

“It requires tillage and we lose too much soil moisture,” wrote another. “Tillage to the extent required to control weeds is too detrimental to soil,” commented another. “I remember the gullies before no-till became effective.”

Organic’s holy grail

The farmers in our survey are on to something. But it goes well beyond these difficult agronomic management issues.

“A lot of researchers in organic say organic no-till is the holy grail,” says Sean Clark, professor of Agriculture and Natural Resources at Berea College in Kentucky. “If you can figure out no-till without the need for herbicides, you can get there.”

New machine technology with built-in artificial intelligence – so-called See and spray tech that can distinguish between weeds and crops – is a potential solution. But no one has consistently made it work yet, and any chemical even applied as a spot spray would be against organic rules.

An even bigger challenge? Organic production cannot yield at same levels as conventional farming, as many respondents pointed out in our survey. One Illinois grower told me his yields were 70 to 75% of his conventional trend yields.

Many organic farmers do find soil quality improvements a few years after transitioning. And many of those improvements are tied directly or indirectly to increases in soil carbon levels (soil organic matter). That's carbon that's not in the atmosphere. Even so, “when people really run the numbers on carbon emissions, a lot of organic products actually have a bigger carbon footprint than conventional,” says Clark, who wrote a paper on the topic here.

One life cycle study of Great Britain showed that an organic-only diet would require five times more land area than currently used, leading to a 70% increase in GHG (read the study here.)

The curse of lower yield has always made organic less sustainable than conventional; now, it is becoming clear that it is also at odds with the urgent need to control greenhouse gases.

Don’t let facts get in the way

Even so, the regenerative ag movement is quickly making its way into popular culture through pop media hits like Kiss the Ground on Netflix. I loved this documentary because it makes people more aware of soil health issues. But there’s that nagging truth no one is talking about: the soil can only sequester so much carbon.

This fact makes the rush to pay farmers through carbon markets problematic. It also puts organic-loving millennials and greens at odds with each other, although they probably don’t even realize it.

“Whether it’s valid or not, regenerative agriculture is coming,” says Clark. “Farmers are going to find a way to get paid from carbon sequestration, but the science shows it’s pretty limited. As they adopt these practices there will be some increase in sequestration, but neither regenerative nor organic is going to make a dramatic difference. The amount of emissions far exceeds the capacity of soil to sequester carbon.”

It’s good to do things to help build soil health. That’s a good idea no matter what USDA or President Biden dreams up. But if you’re thinking about switching some acres to organic, be mindful of where this may put you in the race to get paid for climate-smart practices.

Read more about:

CarbonAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like