Farmers with lots of grey hair – if they have any at all – aren’t the only people hearing footsteps from Paul Volcker’s ghost. Officials at the Federal Reserve appear intent on not repeating the central bank’s missteps from the 1970s that led to Volcker’s Death Star assault.

When inflationary fires first began to burn in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Fed raised interest rates several times, only to ease again when the tightening triggered recessions and rising unemployment. But each time, inflation’s embers reignited until price increases approached 15% in Volcker’s first year as Fed chairman in 1979. Volcker put the hammer down, raising rates past 20% and keeping them elevated long enough to finally kill inflation – along with lots of farmers’ dreams.

So perhaps it’s not surprising officials getting ready for the Jan. 31-Feb.1 meeting at the Fed keeping talking about the 1970s. Trouble is, the market may not be listening.

More hikes ahead

Inflation fueled by the COVID pandemic peaked in June 2022 at 9.1%, and ended last year at 6.5% after the Fed raised the target for its benchmark short-term Federal Funds from near zero to between 4.25% and 4.5%.

Though prices are no longer rising, policy makers at the central bank have signaled their intent to push rates above 5% before pausing. Another quarter point hike is expected to come next week, with similar increases in March and probably May to achieve the 5%-plus goal.

What happens next after that is where the debate really begins. Sound bites from the Fed are talking a tough line. Though they don’t say how long rates will need to stay above 5%, their message is “higher for longer.”

The market, for the most part, isn’t buying it, believing easing will begin quickly, as soon as the Fed’s June meeting, if not sooner. Why the skepticism?

It was less than a year ago that Fed officials repeatedly said inflation would be “transitory.” It wasn’t, so now traders and investors think the “higher for longer” is also wrong.

No 70s Show

Fed officials aren’t talking this week, about anything, at least not in public, observing their unusual blackout period ahead of meetings of the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee meeting. But two days before the radio silence began last week I had a chance to hear Vice Chair Lael Brainard in Chicago.

Economics is called “the dismal science” for a very good reason. Listening to economic speeches is the audio equivalent of watching paint dry. But sometimes, the duller the words, the more important they are.

The title of Brainard’s speech made the Fed’s intentions clear: “Staying the Course to Bring Inflation Down.”

Still, Brainard and other Fed officials, too, believe the inflation of 2023 isn’t a rerun of “That 70s Show.” The difference: Data so far, Brainard said, doesn’t point to a wage-price spiral, where expectations of higher prices keep increasing wages, which fuels more inflation. As a result, the Vice Chair appeared to voice optimism the Fed could engineer a “soft landing,” the monetary equivalent of having your cake and eating it too if rising interest rates slow the economy enough without triggering a sharp increase in unemployment.

Achieving this Goldilocks moment, however, means playing whack-a-mole with markets, tamping down talk that lower rates will happen sooner, not later.

Markets risk volatility

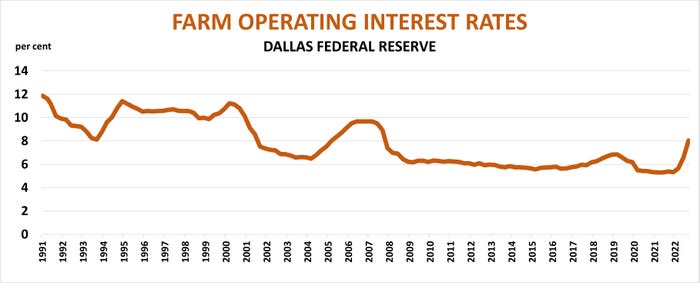

Controlling market expectations may not be easy. Short-term rates keep rising, anticipating the Fed’s next move, taking the cost of farm operating loans higher. The Dallas Federal Reserve earlier in January reported average operating rates topping 8%, the highest level since 2007.

But yields on 10-Year Treasury Notes, which are often used as an peg for farmland loans, fell from a high of 4.25% in October to as low as 3.37% last week.

The dilemma for the Fed is that beginning to lower rates too quickly risks not cutting demand. Keeping demand strong could bring on another round of inflation, made worse if China’s reopening economy begins to consume vast amounts of commodities again.

Hence the tough talk from the bankers.

The risk to farmers is not only more interest expenses this year. A greater threat could come from market volatility if the Fed tries to win its game of chicken with the market. A lot of folks are betting on not only lower interest rates, but on a weaker dollar too as investors dump greenbacks in search of higher returns elsewhere. Even the stock market rallied to start the year, despite lingering fears of recession and weaker earnings. Lots of traders could be caught on the wrong side on markets, with grain futures following a bearish stampede.

Are you elastic?

Another way to avoid inflation would be to increase supply, of everything from workers and housing to fuel and food. In a discussion after her speech, Brainard addressed the supply side of the equation, noting that one reason inflation was so low for so long was because of "elastic” supply chains. If a company needed computer chips, there was always a factory in China ready to expand to provide them.

Farmers, of course, are part of that supply chain, and their ability to increase production around the world, seemingly effortlessly, helped keep food prices relatively low. That all changed, when the pandemic and war in Ukraine disrupted production. Toss in a few droughts around the world and disappointing 2022 yields here in the U.S. and the result is $15 soybeans and corn near $7.

How elastic will U.S. farmers be this year? Farm Futures first survey of planting intentions at the end of summer showed growers ready to cut soybean acres and boost seedings of wheat and corn. The latest survey released last week showed a shift back to soybeans with corn ground increasing much less than in August. So, the jury is still out on U.S. supplies, not to mention what will happen in the rest of the world.

The central bank’s goal is to get inflation back to its 2% target, the level of “rational inattention,” Brainard said, “where people don't have to think a lot about it.”

Ultimately, the Fed and the market will figure it out, but probably not without some surprises – and some pain.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like