Supply chain troubles are being blamed for much of this year’s surge in fertilizer prices, thanks to bad weather and pandemic issues that curtailed production and deepened shipping troubles around the world.

But even after the skies clear and port congestion eases, nutrient costs face an uncertain future. Global food prices and strong demand could keep expenses elevated long after market logjams finally ease.

Fertilizer prices normally soften into the end of the year, providing a double incentive for farmers hoping to delay taxable income by prepaying expenses. The extent of that break ahead of the 2022 growing season, much less whether a collapse in the market could accelerate, make purchases all the more a roll of the dice.

The cost of nutrients for corn shot higher again last week, moving closer to $200 an acre after suppliers adjusted offer sheets to account for the new reality farmers face. Nearly half that bill is for nitrogen, with average farmgate ammonia prices topping $1,000 a short ton. Costs on the southwest Plains closer to major industry hubs range from $830 to $930 while the market further east hit $1,300 at some locations.

Despite those high ammonia values, anhydrous is still far cheaper than alternatives on a unit basis. Average retail charges for urea topped $800 last week while 28% UAN is mostly above $500.

Nitrogen-dependent phosphate products also firmed, with DAP averaging $816 and potash running $769 at in the country.

Retail reality check

Retail prices reflected the reality of short supplies around the Corn Belt for growers planning fall applications as harvest winds down. With shippers no longer accepting load-outs from the Gulf headed to the Upper Mississippi, areas dependent on barges to move product to rail lines and trucking terminals will have to wait until the system begins to reopen in early March. High water is already snarling traffic on parts of the Illinois River, and delays continue to impede movements further south as effects from Hurricane Ida linger.

While the market is still in nose-bleed territory, wholesale benchmarks showed a few signs of hope. Costs at the Gulf were steady to a little weaker, though many international markets continue to churn higher, making U.S. values cheaper that competitors like Brazil. That could discourage imports in the short-term.

Forward prices on futures and swaps offer a mixed outlook. The price curve on Gulf urea futures is $20 higher into spring, with 32% UAN $75 higher. Only DAP deferreds are lower, albeit only by less than $10 than the nearby.

At least some of the fertilizer markets’ troubles stem from high prices for natural gas, the primary feedstock for nitrogen-based products. Spring futures for gas are $2 lower than market-topping January, which would knock around $70 off the cost of making a ton of ammonia.

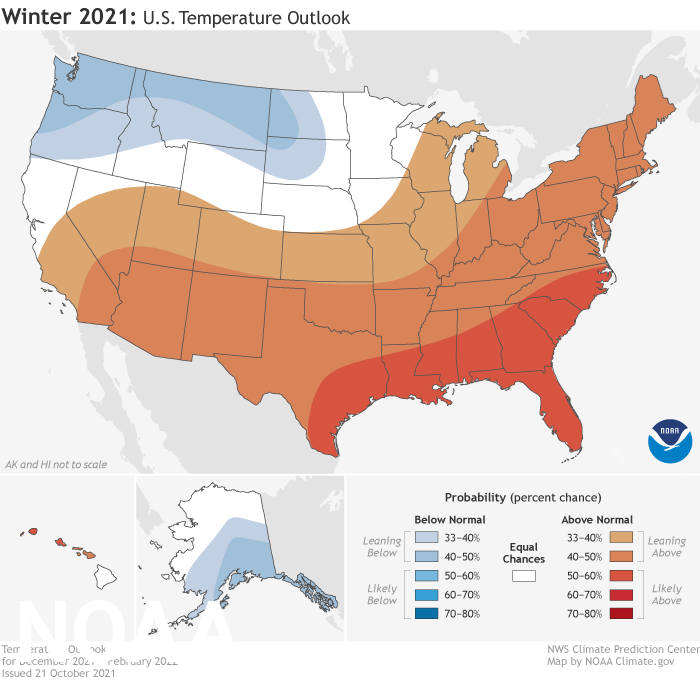

Whether that trend holds depends on weather, and perhaps politics. The official winter forecast for the U.S. calls for above normal temperatures over much of the country, though meteorologists don’t rule out potential for another polar vortex to sweep down from the Arctic similar to the one that crippled Texas and its huge energy industry in February. And, although the U.S. doesn’t put out seasonal forecasts for other parts of the world, the La Nina cooling of the equatorial Pacific now underway is not correlated with colder temperatures elsewhere in the northern hemisphere from Europe to Asia.

But winter weather isn’t the only worry, especially for nitrogen plants in Europe forced to shutter due to lack of gas and high prices. Russia is a big supplier to the region, sparking fears it could use energy as a weapon as rhetoric with the West heats up. Global gas prices are running around six times higher than those in the U.S., as some plants ponder whether to close permanently due to high input costs. If that seems extreme, just remember what happen to the U.S. nitrogen industry two decades ago, when gas prices here exploded, forcing production overseas.

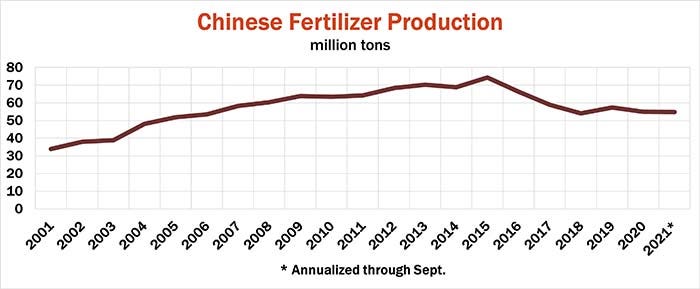

Worries about energy supplies also caused production cutbacks in China, a leading exporter of urea and phosphates. The government in Beijing appears bent on curtailing fertilizer exports to make sure farmers there have enough supply, sparking concerns Chinese sellers would not deliver recent big sales to India, which should be back in the market soon for more. Chinese urea exports jumped in September, and year-to-date shipments are up 37% from 2020, while phosphate sales are 48% higher, prompting the government’s reaction.

While high energy costs threaten that supply now, China’s industry was already slowing down in response to government attempts to curtail pollution – a factor that could come into play this winter ahead of the controversial Winter Olympics set for February. Total fertilizer production in 2021 is down 26% levels from peak levels reached in 2015.

And while COVID rates in China remain relatively low, restrictions are spreading as officials fight to tamp down the pandemic’s spread. Previous lock-downs closed some factories and ports, exacerbating the world’s supply chain problems.

The dramatic increase in fertilizer this year lifted prices to the highest level since 2008. The market collapsed quickly back then in the wake of the financial crisis. But barring another super-bearish black swan event, the market could stay higher, longer this time around.

Without the supply-chain frenzy affecting commodities right now, fundamentals suggest above average fertilizer costs this spring: Retail ammonia around $785, with urea and DAP at $650. Under standard analysis potash would be $420, but that target looks even more unlikely given the uncompetitive nature of the market for those products, which is tightly controlled by a few exporting nations including Canada and the Former Soviet Union.

History over the past decade offers mixed guidance about what moves the market. The best indicator is world food prices, including both crops and livestock. While high crop prices encourage farmers to nourish crops, livestock also factors in, giving that industry leeway to keep feeding animals when rations become more expensive.

The influence of global supply and demand is a bit more mixed. World production of N, P and K is correlated negatively with prices – the tighter the supply, the higher the fertilizer cost. Urea and ammonia are positively correlated with demand – prices go up the more farmers use. But potash and to a lesser extent phosphates are negatively correlated with demand, supporting the notion that farmers cut back on these and mine their soil when prices are too high.

Next: USDA report

The next shoe to drop on the market could be acreage. Though fertilizer prices over the past decade showed a negative correlation to world acres – suggesting lower prices caused farmers to plant more globally – U.S. major crop seedings show a mostly positive statistical relationship. Look for traders to pay close attention to USDA’s first acreage print for 2022, which is scheduled for release Nov. 5. This estimate will be based on economic trends, not farmer surveys, and is published as part of the agency’s budgeting process.

If the government believes higher costs will convince farmers to plant fewer acres of nitrogen-dependent corn, it could finally yank the feed grain market out of its harvest doldrums.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like