“Will high prices cure high prices?”

This question has been at the forefront of nearly every marketing discussion I’ve engaged in this spring. And while the answer to it is obviously “yes,” it is not as simplistic of a solution as it seems. Plus, it’s not likely to happen soon in this country.

High prices being the cure to high prices implies two options for producers: yield or acreage growth. Acreage expansion is the more glamourous option of the two in large part for its visual appeal at the farm level: more acres equal more production.

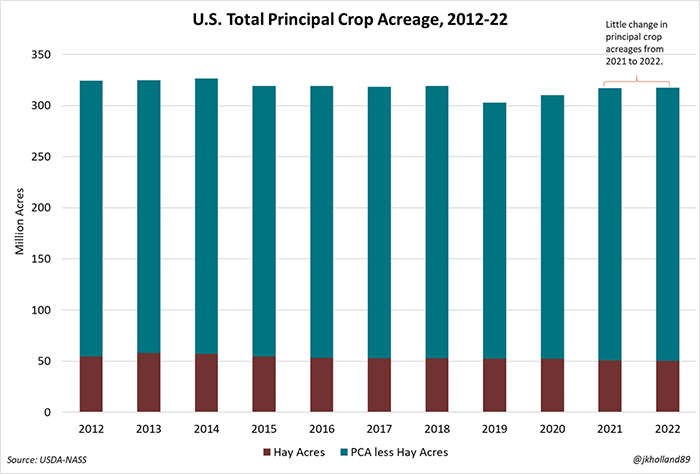

But as USDA’s March 31 Prospective Plantings report found, even with soaring commodity prices this spring farmers resisted a significant acreage expansion in the U.S. this year. Total anticipated 2022 U.S. principal crop area is only expected to rise by a meager 214,000 acres this year (0.07%) to nearly 317.4 million acres. That’s hardly the “acreage expansion” pre-report trade estimates had expected.

Looking further into the March 31 Prospective Plantings report, combined corn and soybean acreage is expected to fall 107,000 acres from last year, going primarily to other crops. Not counting the 2019 prevent plantings year, combined corn and soybean acreage has only varied by about 9.9 million acres over the past decade, suggesting there is little room for additional acreage growth for the U.S.’s top two crops.

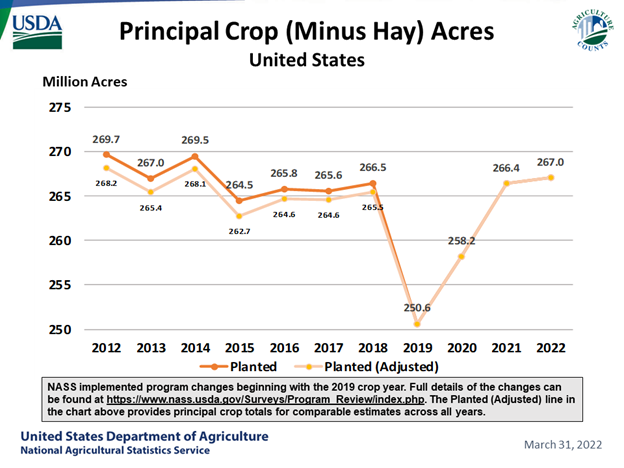

Principal acreage data supports this, as the graph from USDA-NASS Crops Branch Chief Lance Honig shows above. Not counting hay acreage, principal crop acreage has varied by only a few million acres here and there over the past decade. Any seemingly significant acreage shifts are likely to be dependent upon hay acreage, as illustrated below.

But if acres are not expanding in the U.S., they have to be increasing somewhere, right? Right.

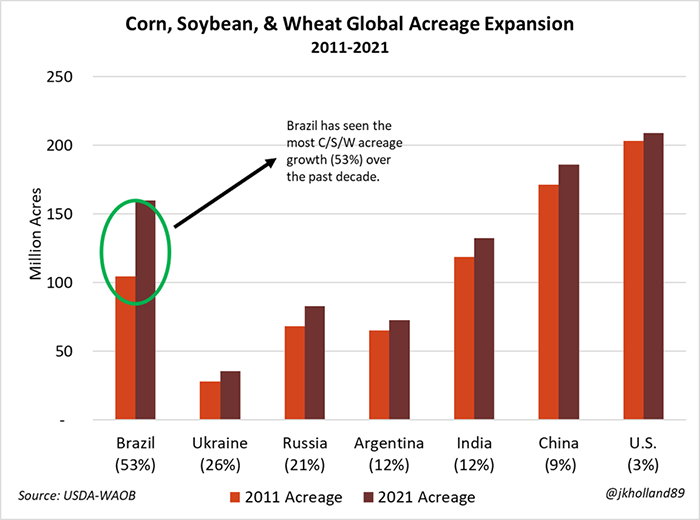

The world added nearly 59.4 million harvested corn, soybean and wheat acres between 2019-2021 – a staggering 4.5% increase. That’s equivalent to all U.S. hay acreage harvested back in the late 2000s over the span of two years. But those increases were not added in the U.S.

Rather, these corn, soybean and wheat expansions over the past decade have been driven by Brazil (53% increase between 2011-21), Ukraine (26%), Russia (21%), Argentina (12%) and India (12%). So the expansion in response to prices is happening but in South America and the Black Sea and not in the U.S.

Brazil’s corn and soybean acreage expansion has culminated in an additional 53.6 million of new global acres harvested over the past decade – just a few million acres shy of expected U.S. hay harvestings this year. Crop expansions in the Black Sea are also a primary driver to the last decade’s acreage expansion, which is proof that high prices do increase production globally, though not in the U.S.

Another acreage option?

Only 20.6 million acres were in CRP in 2021, with enrollment shrinking drastically from its peak of 37 million acres in 2007. About four million CRP acres are expected to expire this year. In 2020, 51% of the 5.4 million expiring CRP acres re-enrolled in the program while only 49% (2.7M ac.) presumably returned to crop or pasture production.

But again – there really wasn’t evidence of CRP acreage helping to boost crop expansion this year in response to high commodity prices. Plus, rising annual rental rates paid by the program offer growers an incentive to keep marginal ground fiscally productive.

CRP acreage is typically ground that produces subpar yields. In the era of high inflation, the cost-benefit payoff of spending high dollars to produce minimal yields is not exactly winning optimization strategy for farmers, especially when they can reap more significant gains from ground with higher yields and lower input costs – and benefit from rising CRP rental rates.

Last week, USDA announced that around 1.7 million acres of CRP land expiring this year would go into crop production following the program’s general sign-up period. However, the smallest volume of new CRP acreage since the program was created in 1985 was added this year (315K acres), signaling that rising rental rates do not offset the opportunity cost earned from commodity production.

“Our conservation programs are voluntary and at the end of the day, producers are making market-based decisions as the program was designed to allow and encourages,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

Sign-up for the Grasslands option of the CRP program, which allows farmers to receive conservation payments while utilizing land as grazing areas, ends this Friday, May 13. With drought persistently battering the Plains for a second straight year, the Grasslands option could help sustain feed sources for livestock in the coming months of what is sure to be another La Niña-induced drought season.

Yield – and planting – focus

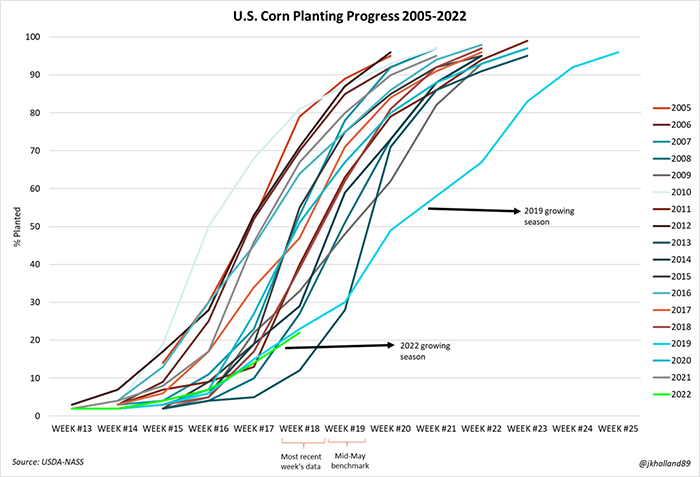

With U.S. acreage likely at its limit, let’s revisit the second option to the original question about high prices curing high prices: yield. In 2022, the answer to that will be more dependent upon yield than acreage in the U.S. With early planting progress largely thwarted at press time in late April, extra acreage is likely out of the question this year for U.S. growers especially as cool and wet weather prevails in the eastern Corn Belt.

But that also means that corn yields could struggle if 68% of anticipated 2022 corn acreage is not planted by May 15. Only 22% of the corn crop was in the ground as of May 8, a staggering 28 points behind the five-year average.

If 68% of the corn crop is not planted at the May 15 benchmark, every percentage point difference in that year’s planting pace and the five-year average translates to a 0.289 bushel per acre change in yield, according to a model outlined in a landmark USDA paper by Paul Wescott and Michael Jewison.

For example, in 2019, by approximately May 15, only 49% of the corn crop had been planted, 33% lower than the five-year average. Factoring in the 0.289 coefficient, the yield loss represents a 9.5-bushel-per-acre reduction (-33 x 0.289 = -9.5) to trendline yields at that time, which were 176.0 bpa. Thus, the model calculated 166.5 bpa for the 2019 yield, which actually came in at 167.5 bpa.

While the timeline for “windows of opportunity” for planting for maximum yields varies across the country, mid-May is largely viewed as the preferred deadline to have corn in the ground to hit optimum yields for the year. Cool and wet weather has largely delayed planting progress this year, though clear and warm weather over the next couple weeks could help to accelerate slow planting paces.

Market watchers are increasingly eager to throw the baby out with the bathwater when it comes to yields correlated with these planting delays. But I encourage farmers to not lose their cool just yet.

There are a multitude of other factors that affect final yield counts throughout the growing season, so remember that it is not solely the planting date that dictates yield, but rather a multitude of compounding factors. “A good share of the variability in yields depends on what happens after planting,” Bob Nielsen, an agronomist at Purdue University, points out.

“The ABSOLUTE yield response to delayed planting is relative to the maximum possible yield in a given year. Consequently, it is possible for early-planted corn in one year to yield more than, less than, or equal to later-planted corn in another year depending on the exact combination of yield influencing factors for each year.”

Possible acreage shifts?

USDA’s June 30 acreage report could still have bullish surprises in store for markets in terms of acreage. With planting delays mounting, there has been early market chatter about some 2022 corn acres – particularly in the Upper Midwest – switching to soybeans as the planting window narrows.

Corn acres did not have a lot of room to give up acreage this year, with USDA only forecasting 89.5 million acres (-4% from 2021) of corn expected to be planted this spring amid high input costs and competitive prices for other crops.

Time will be the ultimate factor in deciding how – and if – acreage shifts impact the soybean market this year. China has cooled its soy export purchases in recent weeks and is expected to see a domestic acreage expansion this spring if all goes according to the government’s plan. Global edible oil supplies are tight, especially in the wake of the Russian war in Ukraine, so any extra soybean acres could easily meet market demand this year, offsetting any potential bearish pressures from higher acreage.

Planting progress – for both corn and soybeans – is looking even more favorable this week than last. While there are some scattered showers on the horizon for this week, next week is looking much warmer and dryer, which should allow for planting progress to accelerate at a rapid clip in the next couple weeks.

But any corn and soybean market expansion hopes in the U.S. lie solely in the hands of yield forecasts this year. And based on how spring weather has shaped up so far, it seems like tight supplies – and subsequent high prices – are likely here to stay for at least another year.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like