One question I’ve been commonly hearing over the past couple weeks is “How soon will the world run out of wheat?” I honestly have not heard a good answer to this one, but there are a few metrics that can provide better insights from Wednesday’s March 2022 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report from USDA into this curiosity.

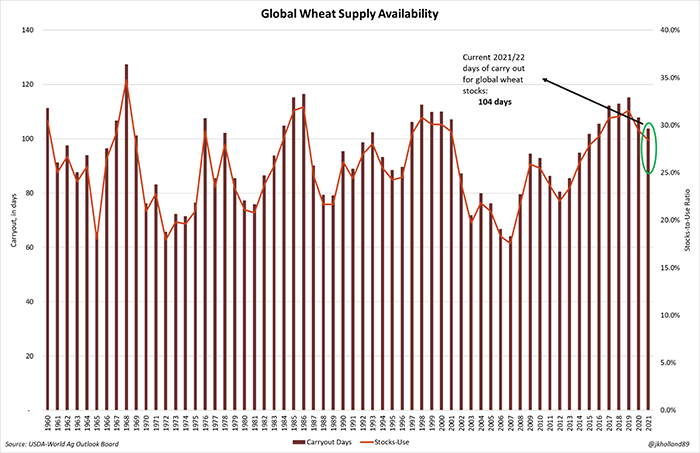

Measuring daily usage rates against ending stocks provides a metric for how many days old crop stock surpluses will last into the new marketing year. This metric, commonly known as carryout, assigns a time value to estimates of how quickly current supplies will last at current consumption levels.

On the global scale, aggregate world wheat supplies currently sit at just about 104 days of carryout. This means that 2021/22 wheat stocks will continue to be used for 104 days after the beginning of the new marketing year when harvest typically begins in the Northern Hemisphere.

That’s just over three months of available wheat supplies when the 2021/22 marketing year ends this summer. The last time it reached similarly low levels was in 2015/16 (102 days). The U.S. typically carries more comfortable wheat supply levels, with the current carry out reaching 123 days. Its previous low was notched in 2013/14 marketing year at 88 days.

If the concept of carry out can be compared to managing financials, carryout is similar to repayment capacity. It is essentially a gauge of the liquidity of available grain supplies and how quickly raw products can be used for human or livestock consumption.

To be sure, the countries that heavily rely on wheat imports from the Black Sea – specifically those in Africa and the Middle East – are likely to be the first to feel the worst pain of high wheat prices and potential shortages.

On Tuesday, we saw some of the ramifications of that pain as Northern African country Tunisia and South Korea rejected all offers on separate international tenders because of high prices. Wednesday’s WASDE report found USDA lowering nearly 56 million bushels (2.4%) of import volumes from Turkey, Egypt, the European Union, Afghanistan, Algeria, Kenya, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Yemen because of Black Sea port closures and fighting.

While northwestern African countries continue to battle a severe drought, their neighbors to the east (Algeria and Tunisia) enjoyed timely showers over the past week that could help to improve yield prospects. Widespread rain and snow across the Middle East last week kept soil moisture levels preferable for winter grain conditions.

Global wheat supplies have been trending tighter over the past three years. During that time, consumption rates have also increased by 7.5%. The global wheat stocks-to-use ratio has dropped 3.1% in that time to a current reading of 28.4%.

High commodity prices will likely deter buyer interest and could trigger famine in countries reliant on high-priced wheat imports, especially after harvest estimates for the 2022/23 Northern Hemisphere crop are gathered.

As production and input costs remain elevated, food prices will also continue to trade at a premium. The U.N.’s FAO warned overnight that global food and feed prices are likely to rise by 20% over the next year on rising input and origination costs, triggering potential famine.

"Worryingly, the resulting global supply gap could push up international food and feed prices by 8 to 22% above their already elevated levels," said the FAO, noting that the global volume of undernourished persons could increase by a staggering 8 million to 13 million people in 2022/23.

That means these top buyers are not going to be desperate for wheat supplies in the short-term, as the forecasts currently stand. The global wheat supply will continue to satiate the world’s craving for the grain, but the current price environment is likely to slow down some of those purchases going forward.

Cooling markets?

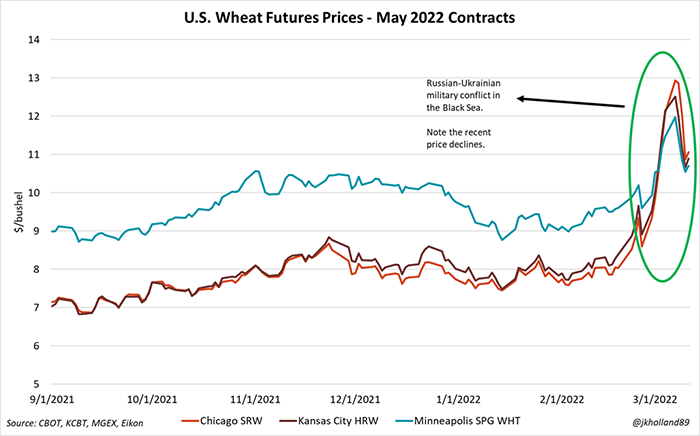

Panic is retreating from wheat markets, as evidenced by this week’s rapid selloff in the U.S. wheat market following last week’s unprecedented rise. The wheat complex is on pace for its biggest weekly decline in 8 years as global trade flows realign and speculative buyers shift their investment capital to equity markets.

"The primary action in the (wheat) market continues to be the rapid erosion of the premium in U.S. basis," Tobin Gorey, director of agricultural strategy at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, told Reuters overnight.

"The scramble for prompt wheat has clearly passed. And the U.S. market is somewhat disappointed that more export sales have not been reported."

While yesterday’s weekly export report showed bullish prospects for U.S. corn and soybean exports, the same did not hold true for wheat. Even with surplus available wheat supplies for export, high prices and freight costs are not likely to make U.S. wheat an attractive alternative for Black Sea buyers.

May 2022 Chicago SRW futures contracts have dropped just over $3/bushel since Tuesday (22%), to $10.60/bushel and change as markets have calmed down following Russia’s unprovoked military invasion into Ukraine a couple weeks ago.

In that timespan, May 2022 Minneapolis futures have shed $1.465/bushel (12%) to land this morning at $10.535/bushel. The May 2022 Kansas City HRW contract has lost $2.215/bushel since Monday (17%), settling around $10.5725/bushel at last glance.

Shifting trade winds

The world is probably not going to run out of grain in the next few months – especially those with readily accessible wheat supplies like the U.S. It may become more expensive, take longer to access supplies when they are demanded, and some high dollar purchases may not go through for less capitalized countries. But the short-term volumes are likely to satisfy food and feed rations for those that can afford it.

The 2022/23 season could be more complicated if Ukraine is not able to sow crops this spring and Russian markets remain inaccessible to global buyers. But this is not a static market and trade flows are already realigning to satisfy demand.

India and Australia have seen demand surges for their wheat over the past couple weeks. India has already snapped up cheap Belarus fertilizers as Western sanctions curbed international interest. China is investing in domestic grain and oilseed production – and likely keeping options open for cheap Russian supplies at the expense (or potential profit) of trading away from the U.S. Dollar.

And high prices will inevitably price buyers out of the market, as we saw with the Tunisian and South Korean wheat tenders earlier this week while prices remained close to 14-year highs. Demand destruction should not be counted out as global buyers increase their worldwide hunt for cheap food and feed alternatives.

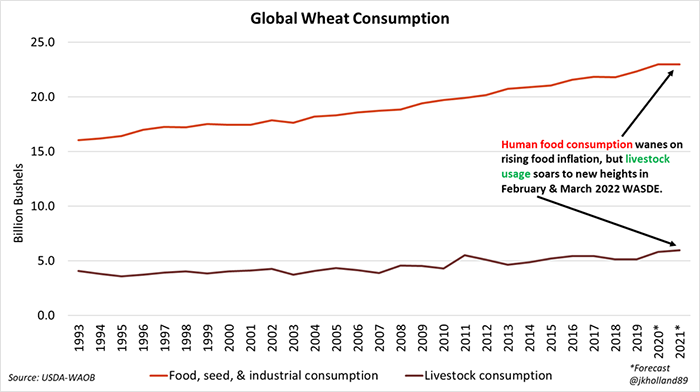

This is already happening for wheat usage for food. The March 2022 WASDE showcased four consecutive months of diminished wheat usage rates for human consumption as prices rose late last year. Since November 2021, USDA has slashed 136.7 million bushels of global wheat consumption for food which continues to stand as a record high of 22.97 billion bushels as global food prices skyrocket.

Marketing strategies going forward

So maybe asking, “When will the world run out of wheat?” is not the most emotionally intelligent question we should be asking as risk managers.

"It's important to point out how a clickbait-driven, attention economy can make this situation even worse. If you take a chaotic situation and throw in more chaos, it tends to generate attention," agricultural economists Brent Gloy and David Widmar write in a recent memo for Agricultural Economics Insights’ Premium Forecast Network.

The most immediate strategy wheat producers can pursue is to continually adjust and analyze on-farm financial outlooks to ensure that your operation has the flexibility it needs to adjust to these rapidly changing markets.

It is not a bad time to lock in high prices by using futures and options contracts. Locking in revenue flows will help to offset high 2022 production costs and can eliminate some price risk. USDA noted in Wednesday’s WASDE report that much of the 2021/22 U.S. wheat crop had already been sold, so it may be time to be aggressive with 2022/23 and even 2023/24 forward sales.

From an operations perspective, wheat growers especially in drought-plagued areas, may need to prepare for future options to supplement revenue, like selling waterway roughage in local livestock markets to ensure cash flows.

As fertilizer prices continue higher, growers will need to plan for input purchases and procurement more strategically to ensure availability and optimal pricing. It’s not too early to start planning for 2023 soil fertility needs. Farmers may need to look to alternative fertilizer methods to withstand the current high-cost environment.

Global wheat supplies are likely to remain adequate for the time being. But as doubts begin to creep in about prospects for the 2022 crop, input costs rise, and re-routed trade flows incur higher shipping bills, expect more market volatility through May, which marks the end of the 2021/22 marketing year.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like