Grain futures don’t always pay close attention to gyrations on Wall Street. But last week’s historic Federal Reserve interest rate hike -- the biggest one-time increase since 1994 -- also pushed the S&P 500 Index into an official bear market. So, should farmers be worried the Fed fallout could derail hopes for moves to record corn and soybean prices this summer?

Yes, and no. Corn and soybean futures do show a positive correlation with the S&P. That is, stocks and grain prices do go hand-in-hand – a little. The connection, though statistically significant, is very small, accounting for less than 10% of the daily changes in those markets.

Still, there’s reason to watch the ticker as closely as the weather forecast. The Fed’s action to raise its benchmark rate by three-quarters of 1% was a mild surprise, not a black swan like the COVID pandemic or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But investors, and not just day traders and speculators, are all to willing to throw the baby out with the bathwater, especially when the broker’s on the phone demanding big margin calls.

More inflation, less growth

Stocks were already on the back foot even before the Fed upped its game to battle inflation – a fight that became more urgent after the Consumer Price Index in May jumped 8.5%, more than expected, with no clear proof prices are peaking. Indeed, forecasts by Fed officials – the so-called dot-plots – called for 2022 inflation to be nearly 1% higher than their last projections, with economic growth slowing even more, to 1.7%.

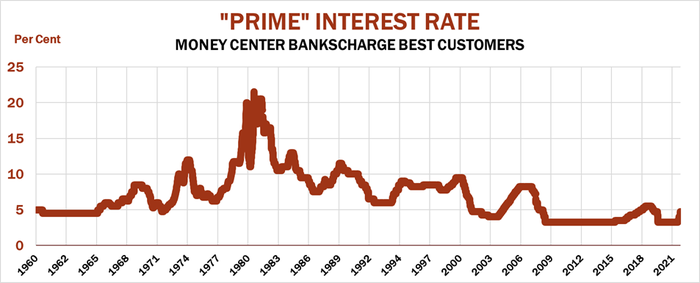

The 75-basis-point hike took the bank’s targeted range for short-term Federal Funds to 1.5% to 1.75%, with the mid-point of forecasts looking for rates to average 3.4% by year-end. With signs inflation is beginning to hit consumer buying power, investors worry squeezed profit margins will pressure corporate earnings, which ultimately dictate where share prices are headed.

The fear took the S&P 20% off its record high close from the first day of trading in January, meeting the official definition of a bear market.

No market goes up forever. Just ask anyone who bought crypto or meme stocks with their stimulus checks from Uncle Sam. But stock market corrections don’t necessarily mean the sky is falling, either. While the S&P witnessed 23 bear markets since 1929, the U.S. suffered only 15 official recessions after that fateful crash nearly a century ago.

How long a downturn?

Indeed, some bear markets touch bottom almost as soon as they begin. That was the case with the severe, one-day plunge in October 1987. While investors back then were also worried about prospects for inflation and recession, the abruptness of the decline may have another source. The market dropped below its 200-day moving average the Friday before the hemorrhage. Investors were just beginning to use personal computers to speed calculation of this technical indicator, and many had their “ah-hah!” moment over the weekend, giving their brokers sell orders that accompanied the rout.

Still, stocks didn’t officially begin the next bull market, gaining 20% off their lows, until March 1988, 20 weeks later.

Sometimes the rebound is far more V-shaped. The March 2020 COVID crash hit bottom just 11 days after the bear market began, and the pain was intense. But after dropping 34% off their pre-pandemic high, stocks in just 27 days rallied back 20% to begin the bull market that just ended.

On average since 1960, the nine bear markets reached bottom in 17 weeks, with 28 weeks between bull markets. If that pace holds this time around, the S&P wouldn’t bottom until October, with a Santa Claus rally at the end of the year kicking off the next bull market.

That 70s Show

The longest bear market, excluding the Great Depression, came in 1973-1974, and took 44 weeks for the market to bottom. The next bull didn’t arrive for another five weeks after that. A recession accompanied this downturn, and it was even longer, lasting until March 1975, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the organization that certifies business cycles.

This was tied with the 1981-1982 decline for the longest post-1930s recession until the housing bubble burst in 2007, the so-called “Great” one that lasted 18 months. Those 1970s and 1980s recessions are of note these days, when many on Wall Street – and perhaps in Washington, too – see stagflation ahead: Poor economic growth coupled with spiraling prices.

While that prospect is the bogeyman for capitalists, the news for farm markets wasn’t all bad in the 1970s. During the 1973-1974 bear market nearby corn and soybean futures rose more than 55%. The opening of export markets highlighted by the “Great Russian Grain Robbery” helped trigger higher crop prices. But by the 1980s, Jimmy Carter’s Grain Embargo and Paul Volcker’s interest rates contributed to corn and soybean futures that dropped 10% to 15%.

Still, it’s hard to discern much of a pattern in how the grain and stock markets dance when bears prowl Wall Street. Corn and soybeans went up four times and down six times during the 10 bear stock markets since 1960. Corn gained around 25% during the up years, losing 13% the others. Soybeans were split, rising 14% over average when they went up and falling 9% when they didn’t.

Long, hot summer?

Traders see more, if smaller, rate increases following Fed meetings July 27 and Sept. 21, and will also watch closely proceedings at the bank’s annual Jackson Hole conference Aug. 25-27. Thin summer trading volume could exacerbate volatility as some investors sit on cash instead of trying to catch a falling knife.

Technicians note the breakaway and measuring gaps created on the S&P chart over the past two weeks, which project a near-term low around 3,500, close to the 50% retracement of the rally off pandemic lows.

Whether that support holds could be important for grain prices. Failure could come in response to another Black Swan, or a return of a familiar one, like Ukraine.

For now, corn and soybeans may focus on weather and upcoming June 30 reports from USDA. Long-term forecasts issued last week by the National Weather Service show warmer and drier than normal conditions spreading from the southwest Plains, with half the Midwest seeing below average rainfall. Forecasts into the end of June are also hot, and in some places dry too, ahead of the key window for corn pollination. And the longer term outlooks hint that soybeans could have some weather headlines later in the summer as well.

USDA’s end of June data dump could also create waves. Slow planting like the rates seen this spring historically are associated with lower final planted acreage in this tally. But the lure of very good profits has some forecasts calling for an increase in corn ground that could offset lower yield potential.

June 1 Grain Stocks, the other report out that day, could also cause waves, as traders wonder if there’s enough bushels to last until combines start rolling through new crop fields.

It all means plenty to watch, and summer doesn’t officially begin until June 21.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like