It’s still early in the spring planting season, but farmers are already behind the 8-ball after a slow start compounded by cool forecasts for May. And growers aren’t the only ones stymied these days. Producers who lived through the 1980s may not have much sympathy for the Federal Reserve, but the central bank’s battle to steer the economy is between a rock and a hard place – and farmers could eventually get crunched if the ship of state runs aground.

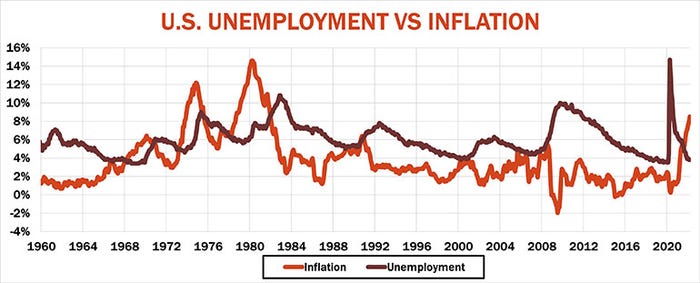

The Fed faces a difficult, perhaps impossible juggling act between its dual mandates for price stability and full employment. To be sure, the jobless rate is near historic lows, forcing businesses to scramble for workers. But the bank’s tools for fighting inflation could derail those gains if credit tightening causes a recession, as it usually does.

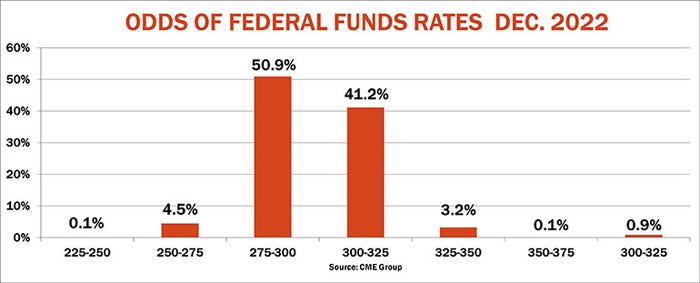

The Fed raised its benchmark short-term lending rate March 16 for the first time since before the pandemic. The move in Federal Funds was modest, just 25 basis points, or one-quarter of 1%, after the target rate held between zero and .25% while the world grappled with COVID.

The bank put its toe in the water last month, and investors expect a complete “everybody in the pool” plunge at the end of its next two-day meeting May 4. A 50-basis-point-hike seems assured, with more following swiftly.

Fed wants “neutral”

The Fed’s long-term goal is to move rates back to normal by removing its monetary policy supports. The latest forecasts from Fed officials put the so-called “neutral” rate around 2.25% to 2.5%. In the short-term, even more aggressive rate hikes may be needed to break the back of inflation readings that pushed the Consumer Price Index up 8.5% last month, the biggest increase in 40 years.

While analysts debate whether we’ve hit “peak inflation,” bets by traders in Federal Funds futures suggest rates could be 2.5% higher by the end of the year, with the benchmark at 3.5% to 3.75% by July 2023.

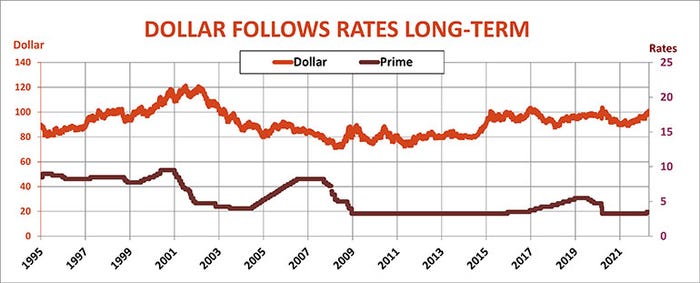

The impact of a rate hike is immediate and obvious. Money center banks follow suit by raising their prime rate charged to best business customers. Prime typically is 3% above the Fed Funds rate. That impacts farm operating loans, with interest on CCC loans rising as well.

Money gets tighter

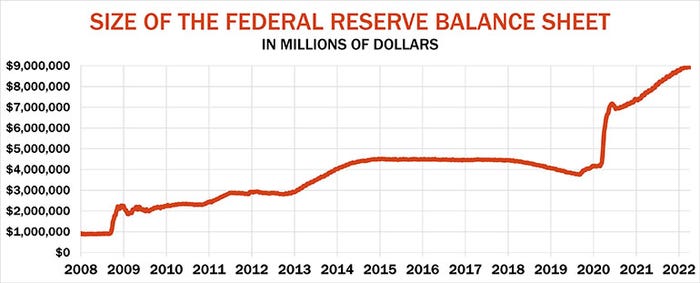

But higher short-term interest rates are only one arrow in the Fed’s quiver. At the March meeting officials also indicated they would begin to transition from QE – quantitative easing – to QT – tightening.

Fallout from QT, which impacts rates on term loans for land and machinery, is harder to predict, but could be equally important.

The Fed controls short-term rates directly by changing its target for Fed Funds. Longer-term rates are set by the market – usually. But during COVID and the 2008-2009 financial crisis the central bank used QE as a lever to keep longer term rates cheap. It did this by buying trillions of dollars’ worth of U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities put out by Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae or Ginnie Mae.

First, the fed injected some $3 trillion into the economy in the darkest days of 2020 to grease the gears of the system with a flood of liquidity. Since then the bank added nearly $2 trillion more to its balance sheet by buying bonds and MBS and by reinvesting interest payments it received along with principal on maturing loans.

All that demand on the buy side raised prices for Treasuries and MBS. Interest rates move in the opposite direction of prices, so higher prices lowered the rates for anyone needing money – and who doesn’t?

Minutes of the Fed’s March meeting show a consensus for reducing the Fed’s holdings by around $95 billion a month. Details of the bank’s plan are expected at the May meeting, though it’s expected to move more rapidly than during the last round of QT in 2017-2019, when the balance sheet shrunk by around $717 billion total.

The Fed is expected to start QT by not reinvesting some interest and principal payments. Still unknown is when and if the Fed might actually start to begin outright selling its holdings. That would accelerate the impact on rates caused by reduced demand and selling by investors who have seen the value of their holdings in public and private debt plummet.

Recession risk rises

Interest rates have a direct impact on farm expenses, of course, but the fallout from the Fed will be felt in myriad other ways as the central bank plays catch-up after first downplaying inflation risk as “transient.”

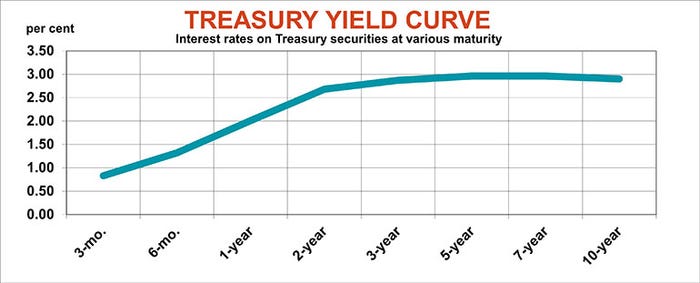

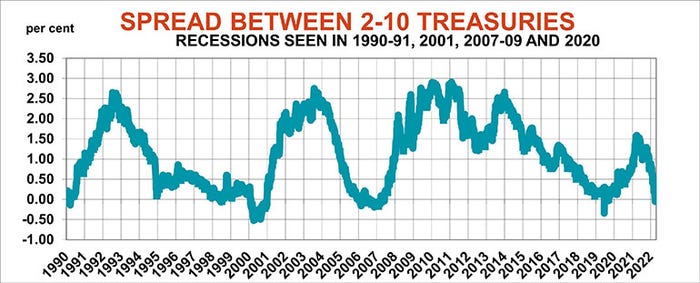

Risk number one is that the cure will be worse than the disease. Odds of recession rise with Fed tightening, and one main indicator watched closely for clues is the yield curve on Treasuries of varying maturities.

The curve “inverted” briefly this month. That is, rates on the 2-Year Treasury Note moved above those on the benchmark 10-Year Note tied to some farm loans. This type of inversion has preceded most of the recessions since World War II, though timing of the downturns varies – usually occurring a year or two after the curve flattens.

King dollar

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added a new twist to the story. Soaring energy costs and sanctions, in addition to fallout from China’s strict COVID lockdown, are expected to lower economic growth around the world. The International Monetary Fund last week slashed its forecasts for world GDP growth through 2023 by a full 1% to 3.6%. Still, while Russia and Ukraine are experiencing sharp recessions, growth elsewhere is forecast to stay positive though at lower levels, with the U.S., Japan and EU falling to 2.3% next year.

Inflation normally is bad for a currency, prompting images of Weimar Germans buying a loaf of bread with a wheelbarrow of Deutch Marks. But with higher prices raging around the world the dollar remains historically strong as the last man standing among major currencies. Not only is the greenback a safe haven, but higher interest rates on U.S. government-guaranteed debt are making Treasuries looking better as an investment for those seeking a risk-free return.

Farmland loses luster

Indeed, “real” interest rates – yields after inflation – ticked above zero last week briefly. More pain for bond holders is still likely but Wall Street traders are beginning to wonder when money managers will flee stocks and other risky assets in masse for the safety of Treasuries.

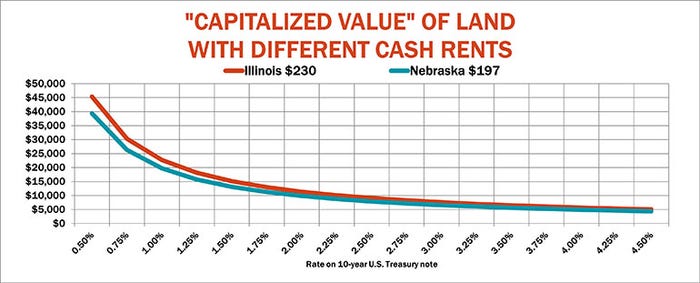

Higher rates also could act as a drag on farmland prices, which so far have been mostly immune to the turmoil of the last few years. Investors value land based on its cash flow from rents compared to yields on the 10-Year Note. Low rates supported land prices even before the 2020 bull market took crop prices to the highest levels in a decade. With rates higher, profits must shoulder more of the burden for supporting land values – profits that are harder to find thanks to near-record costs for fertilizer, fuel, seed and chemicals.

Investors who follow the “capitalized value” of land, of course, are only one class of buyers. Land values haven’t collapsed in part because most land is still purchased by farmers, not pension funds.

Fed prepares for next downturn

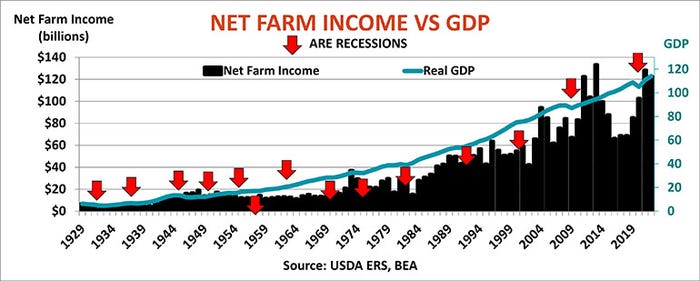

And, while farming sometimes seems immune from what’s happening in the broader economy, recession poses risks for growers too. Since the big crash of 1929 most recessions were accompanied by lower net farm income. That didn’t happen in 2020, but only because of a massive influx of spending by the government that began with the China trade war.

Big subsidies may be harder to put on the table next time, however. With the government hobbled by large debt, fiscal stimulus will be more difficult to finance, and higher interest rates won’t make that any easier. That prospect could put even more focus on the Fed getting back to “normal” – just so it has room to cut interest rates and get the economy going again.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like