August 19, 2020

A previous column I wrote covered the use of red clover to achieve high yields on less-than-ideal drained soils in short rotations.

So, what about the feed quality and management to get that quality crop that’s critical to supporting the greater-than-70% forage diets farmers are switching to? The New York Farm Viability Institute supported our research that looked at this in detail.

Earlier work out of Wisconsin showed that clover maintained high digestibility much later than alfalfa and could be harvested much later for the same quality — at least on paper. Discussing this with a university dairy nutritionist, he stated that a cow’s production drops precipitously when they are fed this later-harvested forage.

With the help of Cornell Cooperative Extension, Pro-Dairy and other Cornell University staff, we established plots in four locations — Delaware, Columbia, Lewis and Essex counties — of identical varieties of alfalfa and red clover. They were planted in replicated strips. At one site, Essex, the alfalfa did not establish, while at the Lewis site the stand was thin and quality samples were valid but not the yield samples.

The second year after planting we harvested samples of the alfalfa and clover twice a week over an eight-week period. Four replications were taken from each crop at each date and immediately frozen. They were maintained in a fresh-frozen state when delivered to Cumberland Valley Analytical Services and analyzed with wet chemistry. The results for each harvest date were entered into Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein Systems model 6.5 by Professor Emeritus Larry Chase of Cornell University.

The target harvest of 40 NDF for alfalfa was used for the red clover. In Columbia County, a warmer location, clover 40 NDF was the same time as the alfalfa — alfalfa on June 5, red clover on June 6. For the cooler, higher-elevation site in Delaware County, the red clover was at 40 NDF on June 16, a week earlier than alfalfa, which did not hit that point until June 24. At the Lewis County site, the alfalfa was only three days earlier than the red clover.

The Lewis and Columbia sites showed that clover is ready at almost the same time as alfalfa. If grown with a grass companion, the harvest date would be much earlier than straight alfalfa. With farmers traditionally harvesting clover or grass well after alfalfa, this would explain why it does not support high milk production — it’s cut too late.

When all sites together were analyzed, the growing degree days to 40 NDF were nearly identical to alfalfa: alfalfa at 901, clover at 923.

I’ve previously written that hairy clover is naturally protected from potato leafhopper. The Columbia research site this year had protected dark green red clover, while the yellow alfalfa was hammered by hoppers. Hairy clover acts as an organic control against potato leafhopper.

Using the common technique of alfalfa height as a predictor of NDF the mean of all the sites was 35 inches tall for alfalfa and 33 inches tall for the red clover. As we passed the 40 NDF date both crops lodged and lost most of their lower leaves.

Analyzing feed quality

The feed quality analysis revealed some key points that are critical for maximizing dry matter intake and milk production. The first is the digestibility. This drives forage intake and milk production. Jerry Cherney, a forage Extension professor at Cornell, has done extensive work with legumes and found that most of the digestion is in the first 12 hours.

When alfalfa and clover were harvested at their respective dates of 40 NDF, the red clover equal or exceeded the alfalfa in digestibility, especially in the higher or cooler elevations. This allows for rapid release of nutrients for sustaining high milk production. Nutritionists still use NDFd30 to compare most forages.

In the warmer and lower elevations when each crop reached its 40 NDF harvest date, the alfalfa had higher digestibility at 30 hours than clover. At the higher, cooler locations, the reverse was true or they were nearly equal.

Sugar, starch, fiber digestibility

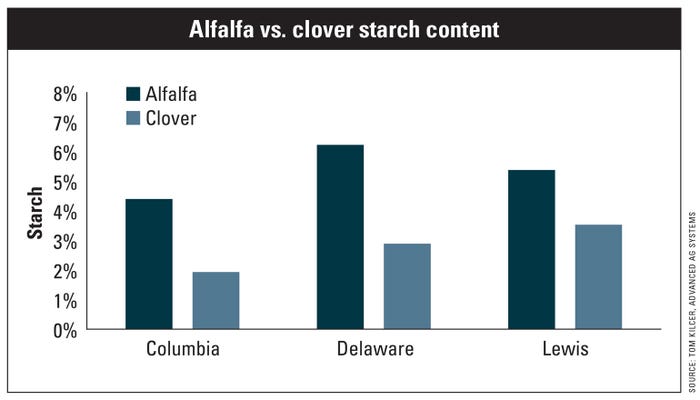

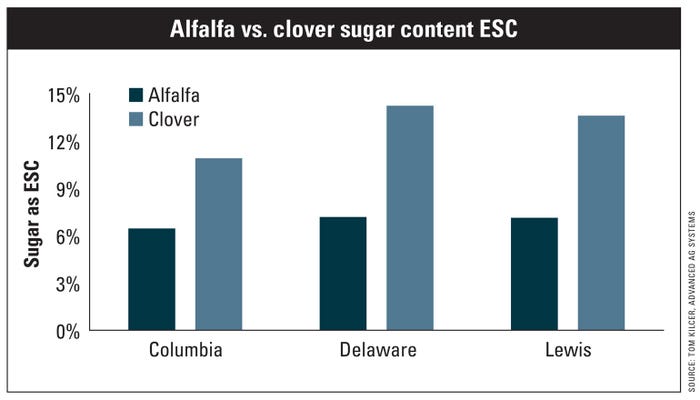

A critical finding was the partitioning of energy produced by photosynthesis. In alfalfa, energy is stored in cellular starch. Starch is composed of 2,000 to 200,000 sugar molecules. Alfalfa had 92% more starch than clover.

Clover, on the other hand, has much higher sugar than alfalfa — 87% more. This has two implications: First, with a proper inoculant, it provides a substrate for very rapid fermentation. Second, it is even more critical to use wide-swath, same-day haylage with clover to preserve that sugar energy to the mouth of the cow.

We hypothesize that the occasional reports of cows not wanting to eat red clover may be due to narrow-row, multiday drying systems that respire most, if not all, the readily available sugar in the plant.

But clover also stores considerable energy in pectin. There is not a direct test for pectin but it shows as nonfiber carbohydrates, or NFC. Clover consistently had higher NFC (13%) than alfalfa.

The uNDF240om was lower for the clover compared to alfalfa across all harvest sites. The alfalfa averaged 20.29 while the clover averaged 17.45. At uNDF30, they were nearly equal.

Clover also has slightly less crude protein — 17.07% — than alfalfa — 19.02%. The total amount, though, is only part of the story. Clover has compounds that inhibit hyper ammonia rumen bacteria from breaking protein to inefficiently utilized ammonia, increasing the metabolizable energy for milk. Clover also has polyphenol oxidase enzymes that inhibit protein breakdown for more bypass protein — 25-35% — than alfalfa — 15-25% — thus enabling lower-cost rations as they have less added, very expensive bypass protein.

Potential milk produced

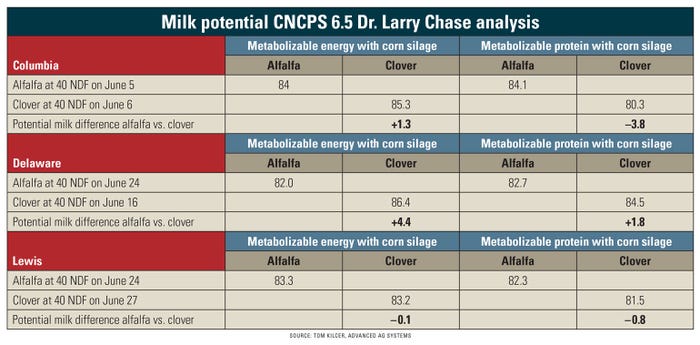

The bottom line is the milk that can be potentially produced. We used the points for each site when clover and alfalfa were harvested at their respective 40 NDF date. Utilizing a diet of 65% forage, of which 60% was corn silage and 40% either red clover or alfalfa, the metabolizable energy (ME) and metabolizable protein (MP) milk supported was determined at each harvest date.

At the warmer Columbia site, there was a 1.3-pound increase in the amount of ME supported by the clover compared to alfalfa. When it came to MP, there was 3.8 pounds of milk reduction when clover was substituted for alfalfa silage. This was expected as clover had 3.4% less crude protein than the alfalfa.

At the cooler Delaware site, the differences shifted significantly in favor of the clover. The ME production was 4.4 pounds higher for the clover than alfalfa when they were substituted for each other. For MP in the corn silage diet, there was a 1.8-pound potential milk increase when clover was substituted for alfalfa in the same diet.

In Lewis County, clover and alfalfa were nearly the same in ME with clover only 0.1 pound less. MP was similar in that the clover was only 0.8 pounds less. Keep in mind that at this site the clover averaged 3.93 tons of dry matter in just the first cut.

Clover can be a superior forage on farms that are affected by the cloudy, cool conditions downwind of the Great Lakes and in higher, cooler elevations, and in less-than-ideal drained soil.

A critical point is to use modern red clover varieties with disease resistance and improved productivity.

Kilcer is a certified crop adviser in Kinderhook, N.Y.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like