The formula for profit on corn or soybeans sounds simple: Yield times price minus cost. But plans made in winter and reality at harvest can result in something completely different.

All three variables in the profit equation are only beginning to come into focus for 2023 crops.

Over the past few weeks USDA provided initial guidance for the coming year in reports from two of its wings that mostly flew under the radar, as traders focused on the here and now. First, The World Agricultural Outlook Board Nov. 7 published its Early-Release Tables from USDA Agricultural Projections to 2032. This so-called baseline about the future is rightly ignored except for one key set of numbers: The first supply and demand forecasts for the coming year, including acreage, yields and prices.

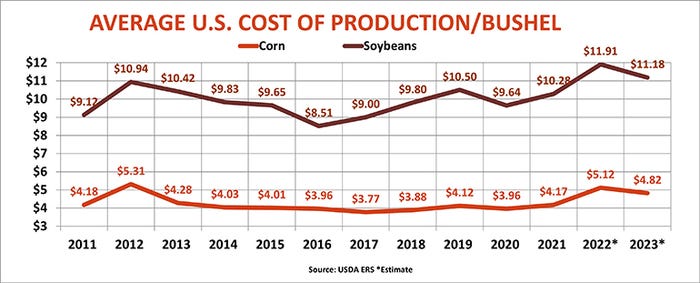

Then on Nov. 15, the Economic Research Service put out updated Cost of Production Forecasts with guidance on what to expect in 2023.

Both of these reports are based on statistical guesses, not surveys of farmers. The baseline forecast used 2022 crop data from USDA’s October World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates as a starting point for 2023, so it’s already a bit out of date. World events – the Ukraine war, tensions with China, a teetering global economy – make any assumptions about prices and costs highly variable. And weather, as always, is difficult to predict six months in advance of a long growing season.

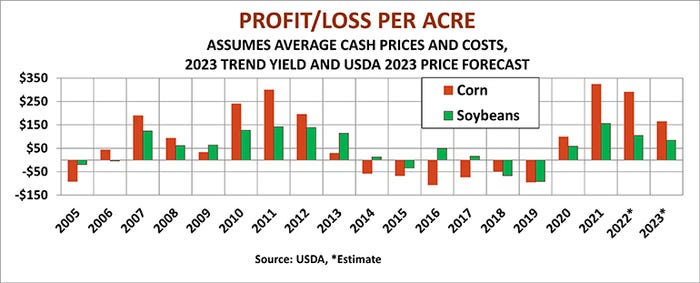

Fine print aside, pushing a pen through your fields looks promising. Both corn and soybeans project profits – if USDA’s projections become reality. Here’s what the new crystal ball says, and what could get better, or worse, about the outlook.

Corn beats soybeans

For corn, the baseline’s 2023 yields of 181.5 bushels per acre and $5.70 average cash price received spells revenues of $1034. Total costs of $870 per acre would generate a profit of $164, down from an estimated $290 this year and a record $323 in 2021.

Soybean yields of 52 bpa and average cash prices of $13 produce revenues of $676, less costs of $591 for a profit of $85, compared to an estimated $100 in 2022 and a record $156 for 2021.

What to make of these early projections?

USDA uses an adjusted trend yield in estimates until its first survey of farmer’s opinions in August. This projects yields over time to account for rising productivity, assuming normal growing season weather. The yields published in November appear to be a rounded average of the statistical and with the weather-adjusted yield. In my own early forecasts I rely on just the projection from the trend over the previous 20 years. For corn this is lower than USDA at 177.6 bpa, for soybeans a little higher at 52.5 bpa. Of course, these trend yields could change a little depending on final 2022 yields reported in January.

Total 2023 supplies combine production and imports with old crop inventories left over at the beginning of marketing year Sept. 1. Old crop carryout likely will change in coming months, but maybe not by enough to be significant, and imports also don’t vary all that much from year to year.

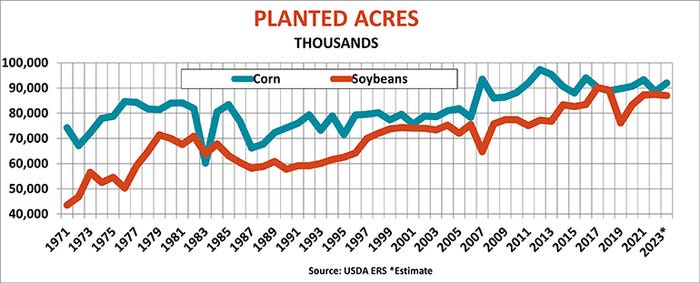

Production is a function of harvested acres times yield. Assuming normal rates of abandonment, USDA put corn seedings at 92 million planted with 84.1 million harvested. Soybean plantings were at 87 million, with harvested acreage at 86.2 million.

Corn acreage surprise?

On the supply side, acreage is where the real debate starts. Projected profit differentials aren’t the only factor affecting farmer planting decisions, but they are important, accounting for 61% of the variance in the ratio of corn to soybean planting intentions reported at the end of March. USDA’s baseline called for 6% more corn acres than soybeans, but the profit differential suggests the corn advantage could be much greater. While soybean acreage could drop, it’s more likely farmers would opt to add corn with profits good to get rotations back in line after cutting corn ground in 2022.

More acres would increase corn supplies if yields hold up, putting additional pressure on demand to keep stocks and prices in line. Early forecasts call for 2023 world acreage and production to recover, limiting our exports, swelling the U.S. surplus, and sending cash prices and futures $1 or more lower.

Rising soybean production in South America could have a similar effect on prices. Of course, it will be months before even 2022-2023 crops are harvested in Brazil and Argentina, where dry conditions are already causing concern – yet another variable that could upset any early calculations about prices.

Other side of the ledger

Costs per bushel vary with yields, but total expenditures could also change from USDA’s recent estimates. Rising interest rates could affect loan payments more than estimated, and energy costs are also subject to the whims of the market. But USDA forecast a drop in costs per acre in 2023 in part due to easing fertilizer bills from the records set this year.

While USDA sees only a modest reduction of 3% in nutrient expenses, actuals could be lower. Farmers buying N, P and K for fall applications paid 10% to 15% less than records this spring set after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Whether prices continue to fall depends significantly on global food prices, with crop acreage and demand also impacting the market. Based on current grain price forecasts, the U.N. Food Price Index could fall 17% from the record set this year – it’s already down 9%.

International fertilizer markets appear to factor in this decline, but those reductions have yet to show up in the farm supply chain. If they ripple through – a big if, considering potential for shipping and other disruptions – costs could fall. Ammonia could trade from $1,065 to $1,130 at the farm level under this scenario. Retailers on parts of the southwest Plains closer to major producing areas are already in that range, so it’s not an impossibility. December ammonia contracts at the Gulf are expected to settle at a substantial discount to the current price of $1,045.

Potash prices could also fall from current farmgate averages around $825, but price declines may depend on what happens to exports out of Russia and Belarus. Russia is pushing to remove roadblocks to deals and could work out a framework with the West similar to its shaky grain agreement to permit Ukraine shipments out of the Black Sea. If trade normalizes, retail potash could dip all the way back to the $615 to $695 level.

Phosphates could also be headed for a fall from recent retail levels above $900 to around $670 to $740 if all goes well. Gulf swaps showed a $50 break into spring last week.

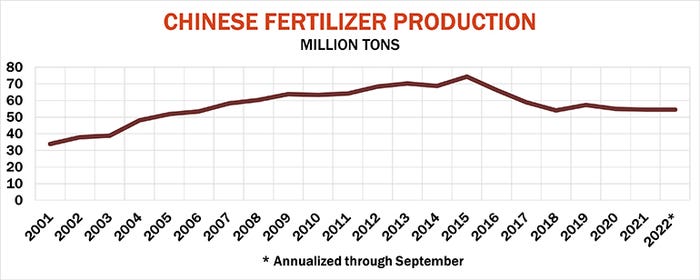

Phosphate compounds, and urea too, could be influenced by whether China returns aggressively to the international market. Chinese fertilizer production has been essentially flat since 2020. First the government pressured manufacturers to limit sales and keep supplies at home as its corn surplus fell. Then COVID lockdowns hit many plants. Overall fertilizer production did pick up in September but year-to-date phosphate exports are down 55%, while urea sales are down 61%.

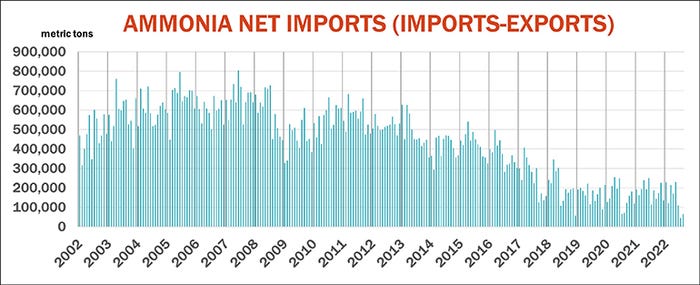

For clues on the international market, watch what happens with U.S. inventories at the Gulf. U.S. nitrogen exports are down 22% so far in 2022 but net ammonia sales picked up 41% in September as prices here were low enough to encourage foreign buyers to take cargoes. For better or worse, fertilizer is an international market. U.S. natural gas prices remain low compared with the rest of the world, which could create headwinds for growers looking for lower costs.

.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like