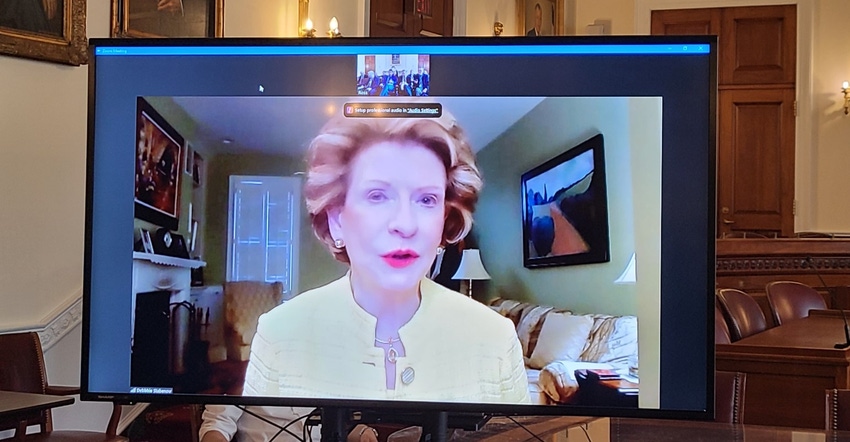

The writing of the last farm bill in 2018 required very few tweaks from the 2014 Farm Bill as prices were stable and few changes were needed, explains Senate Agriculture Committee ranking member John Boozman, R-Ark. But as he and Senate Agriculture Committee Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., look to work on the next farm bill, it’s going to be a very different environment heading into the legislative process.

Big questions ahead relate to permanent disaster assistance, conservation funding and how to address rising input costs while still keeping farmers in business.

“We’ve got these really high input costs. We’ve got high commodity prices, but very, very high inflationary inputs and problems with the supply chain. Hopefully those things will lessen as we get into the middle of next year, but I don’t think so,” warns Boozman.

While speaking to members of the North American Agricultural Journalists on April 25, I asked Boozman how he thought the timeline might play out for the farm bill writing process and how this year may be different than past years. He says members on both sides of the aisle are working on hearing from stakeholders before they start to legislate. His counterpart in the House, Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson, R-Pa., actually criticized the lack of oversight hearings on the last farm bill in preparation for the next one.

Boozman says as you look at labor concerns, inflationary pressures, supply chain shortages and commodity prices, all of those do not look to resolve quickly. “I think these are going to be around for a while.”

Stabenow adds that farmers are faced with a series of new challenges coming out of the pandemic, as she also mentioned the supply chain issues, cost of food, consolidation and lack of competition, the climate crisis hitting growers every single day and now the war in Ukraine.

“We have really important work to do, and how we’re going to assess what have been multiple additional risks in addition to what our farmers usually face,” Stabenow says.

“Unfortunately, the climate crisis is not going away, but increasing in intensity,” Stabenow adds. She’s been trying to get additional money approved in some legislative vehicles that would boost the conservation spending, and also the overall farm bill baseline. She plans to continue to support farmers and ranchers for doing more comprehensive conservation efforts that are directly related to the amount of carbon going into the atmosphere and how to address the carbon prices and also create a voluntary carbon market that will reward farmers who do the right things to help with all of these challenges.

Related: Senate kicks off farm bill discussion in Michigan

Meanwhile, Thompson touted the role of conservation programs and the over-subscribed programs such as the Environmental Quality Incentive Program or EQIP. He introduced a bill – the SUSTAINS Act – which actually allows for additional conservation funding be paid to farmers through private partnerships.

“We hear about carbon banks because big corporations want to be able to show their climate credentials. I appreciate that, but I’ve got a better way for it,” Thompson says. “We’re hoping we can make this bipartisan where the SUSTAIN Act creates a public-private partnership that large organizations and corporations can make a contribution to.”

Thompson explains the beauty of it is that local Mom and Pop feed stores or grocery stores can make a smaller contribution and would get the same climate credentials as the larger corporations. All the money would go to USDA to help pay for additional conservation programs or help fund those programs that are oversubscribed.

Fertilizer and rising input costs continue to be top-of-mind for farmers, but how to balance those within a safety net or other government program continues to be challenging.

Chandler Goule, CEO of the National Association of Wheat Growers, says many stakeholder organizations are looking for creative ideas for limiting the impacts of rising input costs. For instance, to help with fuel costs, some individual states are looking at offering a gas tax holiday, taking the fuel tax off for agricultural use, or lowering the agricultural use fuel tax from the current level.

Boozman says he plans to know more in the months to come on the impacts of the higher inputs and whether it impacts what crops to plant such as less corn acreage and more soybeans. He says then he can more closely examine the current farm bill safety net of crop insurance and the Average Revenue Coverage and Price Loss Coverage to see what needs to be changed to keep an adequate safety net in light of rising inputs.

Another important issue is how to handle disaster programs. Boozman says USDA currently provides an effective response to catastrophes, but sometimes it can be two years before producers receive disaster payments. Thompson says whatever is done on a permanent disaster program, it “shouldn’t impede crop insurance.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like