You know how any discussion about competition between the U.S. and Brazil involves lack of infrastructure in South America? How all those South American dirt roads couldn’t compete with our highway, train and waterway pipelines?

That’s about to change.

The Brazilians may not have sent you a Valentine’s Day card this year, but they were likely thinking of you on Feb. 14. That’s when Brazil President Jair Bolsonaro flew up to Para state to celebrate the completion of a paving job that could change the competitive field for grain markets. Brazilians finished paving a road that until now, was more of a mud trap that swallowed trucks on their way from soybean-producing Mato Grosso state to ports on the Tapajos River, an Amazon tributary.

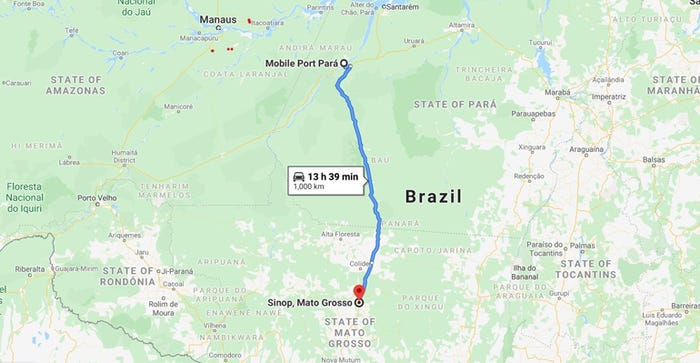

Highway BR-163 will provide cheaper transport costs between soybean-producing Sinop, Mato Grosso, and the exporting port of Itaituba.

You may have seen the famous photos of grain trucks being swallowed in axle-deep mud as they struggle to go north from production areas to rivers along the federal highway known as BR-163. Stranded trucks racked up thousands in losses for grain traders (see story here).

Some producers put up with it because ports on the Tapajos are only about 600 miles north of say, Sinop, Mato Grosso, a major soybean-producing area. But it’s more than twice that far to the big southern port of Santos, just outside São Paulo.

A pickup truck drives near construction of the Trans-Amazonian highway (BR230) near Ruropolis, Para state, Brazil. - The BR230 and BR163 are major transport routes in Brazil.

Much of the pavement of BR-163 had already taken place over the nearly 60 years since the dirt road from Cuiaba, Mato Grosso to ports on the Tapajos River began. But there’s been this nagging 30-mile stretch that’s been the holdout. And with good reason, some say.

They would point out it’s bad enough that the old dirt BR-163 cut through national parkland and skirted awfully close to Indian reservations. But those against paving the rest of the federal highway fear development would not stop there. With increased truck traffic would likely come tire repair services, truck stops, motels, and so forth to this pristine area.

But the current administration, uninterested in such things, finished that last stretch of BR-163 by mobilizing a couple of engineer corps from the Brazilian Army to get things done.

Brazilian engineer battalions celebrate the completion of paving operations of highway BR-163. The finished roadway could cut transport costs 15% to 20% and double corn/soy exports from Mato Grosso within 5 years.

Lower costs, more beans and corn

Brazil’s oilseed crushers association estimates completion of that last 30-mile stretch of dirt road between the capital of Mato Grosso to the port at Itaituba will double corn and bean exports from Mato Grosso to the Tapajos River ports within 5 years -- and it’ll do so because highway transportation costs should drop by 20% due to quicker transit times, fewer delays and so on.

According to the crushers, that would mean BR-163 will go from handling about 10 million tonnes of corn and beans to about 20 million tonnes by 2025.

Your ‘competitive advantage’ is about to shrink.

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like