In 2015 poultry producers in Iowa and Minnesota were caught off-guard when the avian flu outbreak swept through poultry operations. When it subsides, some 48 million birds were dead, and feathers were ruffled amongst some producers, industry people, regulatory people and the public alike.

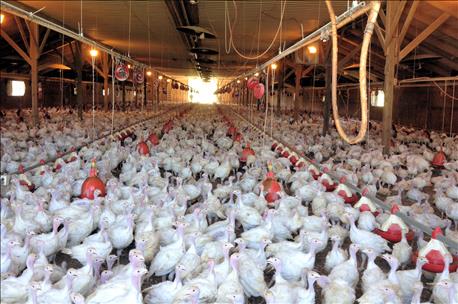

FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN: Some workers last summer refused to return to barns where birds were infected. There was a need for education, and Denise Derrer says education became part of Indiana’s response plan. (Photo courtesy of Minnesota Turkey Growers Association)

While no one wants to benefit from someone’s bad fortune, only someone with their head in the sand doesn’t study what happened and learn from what transpired. It appears that the Indiana Board of Animal Health not only paid attention, they held meetings and discussions, and prepared emergency plans based on what went right and what went wrong in those other states. Last year Indiana’s risk was limited to one backyard poultry flock. The state reacted by banning poultry exhibitions and sales of poultry at auctions and flea markets. The action seemed prudent at the time. A step-back view from the distance of time and education has led to a different path. Exhibitions won’t be banned, according to Denise Derrer, communications director for BOAH, but more recordkeeping on those types of sales and projects will be required so that birds could be traced if necessary.

Here ae just three incidents from the outbreak in 2015 that left an impression on regulators, and prompted planning to avoid those situations here if disaster struck, and it struck!

1. The flat duck phenomenon

Emotions often ran high in communities affected last year, Derrer says. Many dead birds were transported to landfills. In one instance someone spotted a dead bird on the road, assumed it had fallen off a truck carrying euthanized birds to the landfill, and caused a raucous since people thought the effort was sloppy, and dead, possibly diseases carcasses weren’t being handles correctly.

As it turns out, when someone looked closer, the bird in the road was a dead duck, flattened by a car or truck, and had nothing to do with the ongoing crisis. But the damage had been done. Education in advance is important to calm fears, Derrer says.

2. My husband isn’t going back in that barn crisis

Due to reports floating on the Internet and social media, wives of workers at some of the large farms were home worrying while their husbands were working, or vice-versa. Someone got a report that said avian flu could transmit to humans. At one point, a sizable number of workers at some farm refused to go back into the barns to finish clean up because their spouse and families feared for their health.

“The truth is that there is very little risk of humans catching it, and it has been confirmed by medical authorities,” Derrer says. “But even with protective equipment offered, it took a long time to convince workers it was safe to work in the barns.

3. “I’m from the government and I’m here to help”

Some states don’t have strong leadership like we’re blessed with here in Indiana, Derrer notes. Brett Marsh, state veterinarian, is the longest-serving state vet in the country. In other places USDA takes over to fill a void.

“We’ve been appreciative of their help, but Marsh was adamant we would stay in control of the situation,” she says. “When the ordeal is over, USDA packs up and goes home. We are left to work with the people and put the pieces together. Good relationships with producers are important to us.”

Based on everything we’ve heard so far, congratulations to BOAH and other homeland security partners for getting a firm grip on what could have quickly become an out-of-control trainwreck. It‘s still a major setback and tragedy for producers. But hopefully it’s one they can survive.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like