Shock. Chaos. Scramble. These three words describe the farming community’s reaction after a ruling by the U.S. 9th District Court of Appeals vacated three EPA dicamba product labels in early June.

Bayer’s XtendiMax, BASF’s FeXapan and Corteva’s Engenia are three products used as part of the Xtend system for growing soybeans and cotton. According to Bayer, the company expected Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans to be planted on 50 million acres this year, and XtendFlex cotton to be planted on 10 million acres nationwide.

By June 3, many soybean and cotton growers already had their dicamba-tolerant seed in the ground. Some of these acres were sprayed under these approved EPA labels, while others were not. But on that day, it became illegal to spray any more acres.

It took the EPA five days to come up with an alternate plant that allowed farmers and agriculture retailers to spray products until July 31. But what happened during those five days and the days after still linger in the minds of farmers, retailers and weed scientists across the country.

Hurt by dicamba

“It was shock,” Pam Rowland says of when she first heard the news of the court ruling to ban a product that damaged her crops and business starting four years ago.

“For one, because I didn’t think that it was right that they did this right in the middle of the growing season because farmers already had dicamba-tolerant beans planted,” she explains. “They bought the chemical, so that was hard.” But she is also pleased.

“I’m kind of glad it’s going to be gone,” Rowland adds. “I know the dicamba technology is effective in weed control for many crops and farmers will be upset when it is off the market, but I couldn’t believe they finally did something about this.”

Rowland’s family farm and business were directly affected by the introduction of dicamba-tolerant crops and the subsequent dicamba herbicide products.

At that time, she and her husband, Gene, were partners with their daughter and son-in-law on the farm in Stoddard County. They raised and sold conventional or non-GMO beans. “It is not that we are anti-GMO,” she explains. “It’s just those were good yielding University of Missouri developed varieties, and there was a market for them.”

The couple also has a seed-cleaning business for wheat and soybeans. Customers would save soybean seed, bring them in, and the Rowlands would get them ready to plant next year. It was a good business. “We used to have a whole warehouse this time of year full of soybean seed that farmers save,” she says. That was before dicamba-tolerant crops came on the scene in 2017.

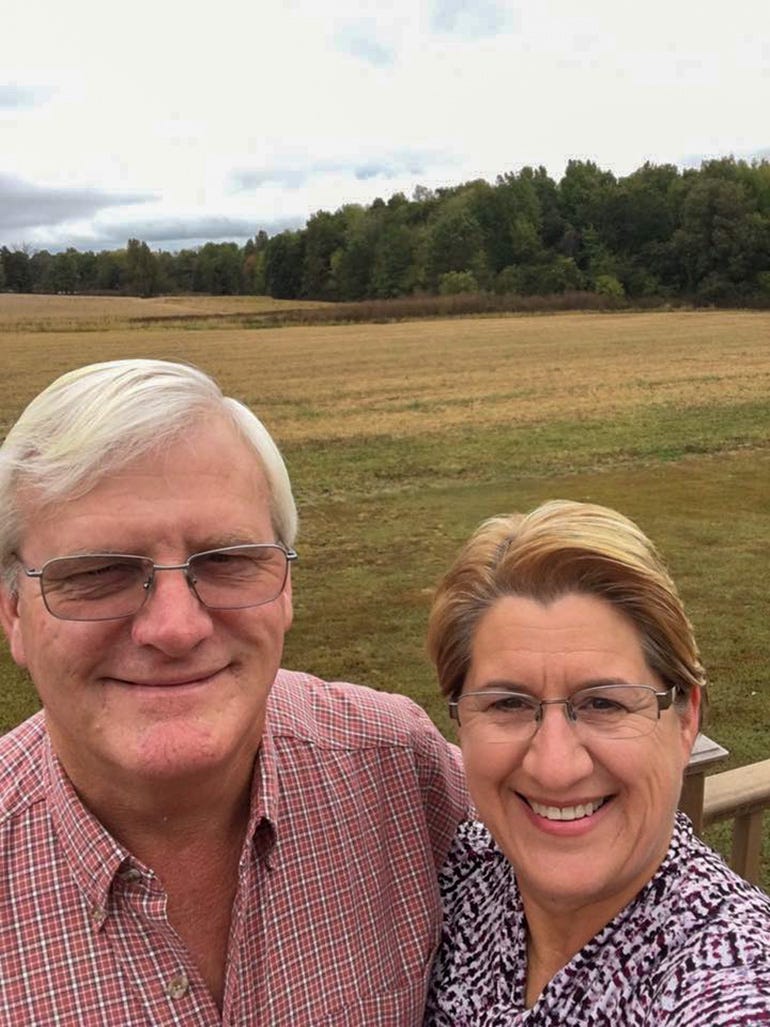

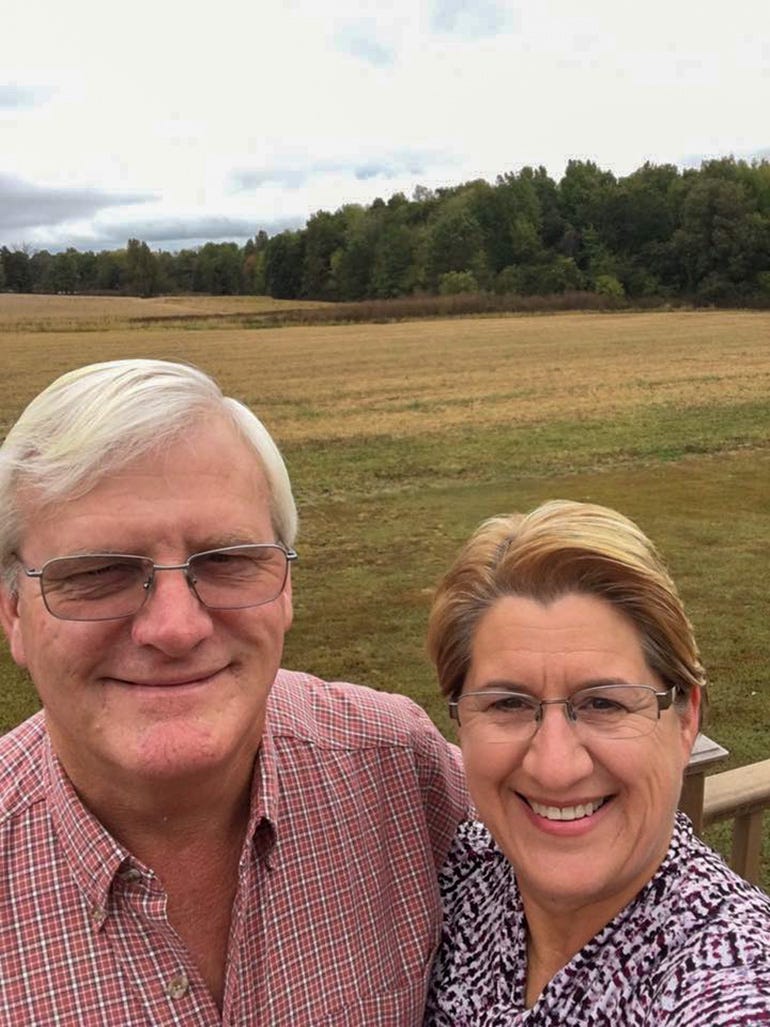

MIXED EMOTIONS: Gene and Pam Rowland own a seed-cleaning business and help raise conventional soybeans on the family farm in Stoddard County. Drift from current technology hurt both parts of the operation. While Pam is pleased the products are banned, she did not approve of how it affected farmers over the past three years.

The market for nonconventional beans has pretty much dried up, Rowland says. “Everybody around here has gone, with the exception of a handful of them, to planting dicamba beans just to avoid getting damaged,” she says. The seed-cleaning business suffered as farmers were no longer holding back conventional soybeans.

Dicamba volatilization in 2017 hurt farmers such as the Rowlands. During that year, farmers who planted either dicamba-tolerant soybeans or cotton made over-the-top applications of old dicamba formulations. It was off label. The impact was widespread, with damage to neighboring fields not planted to dicamba-tolerant crops.

Then came the approval of new, legal dicamba technology — XtendiMax, Engenia, FeXapan and Tavium. Still, Rowland says damage to crops continued, and it wasn’t just soybeans. She saw farmers and even city dwellers face production losses in gardens, fruit trees and ornamentals.

Her farm suffered. Her business suffered. Still Rowland is not anti-farmer, ag business or ag technology. When it comes to these registrations and their potential renewal, she says, “My hope is they can get a formulation that doesn’t volatilize and just stays put, where you put it.”

Ultimately, Rowland holds the same view she did four years ago when these products came to the market. There is room for everyone in agriculture, however, she says, “I just think what I do on my farm should not negatively impact you on your farm.”

Products on hand

Agriculture retailers had XtendiMax, Engenia and FeXapan ready to apply to fields across the Midwest. When the San Francisco court ruled to stop allowing application and sales of these three herbicides, Steve Taylor, Missouri Agribusiness Association executive director, says it brought “chaos” to his members.

Taylor says he has never seen a court make such a ruling, bypassing the EPA’s registration process in an attempt to pull a label in the middle of a spray season, and adding that businesses rely on following the label, and when it is vacated midseason, it is hard to manage.

Almost immediately, Taylor received phone calls, emails and texts. “Ag retailers were confused,” he says. “Our farmer customers, rightly so, were confused and frustrated.”

He says, like farmers, not all ag retailers agree on the products. “Everyone has their own opinion,” he notes. “People can question the label, but you shouldn’t be allowed to pull it in the middle of the season. That is not the way to do it.” To him, the court was actually “invoking chaos into the system.”

He cites their own ruling that states, “We are aware of the practical effects of our decision. Among other things, we are aware of the adverse impact on growers who have already purchased DT soybean and cotton seeds and dicamba products for this year’s growing season, relying on the availability of the herbicides for postemergent use.”

“They knew it was going to harm farmers,” Taylor adds, “and they did it anyway. It really left our ag retailers and farmers hanging.”

He was relieved when the EPA came out with its interpretation of the ruling and allowed for product sold by June 3 to be applied through July 31. Still, he says something needs to be done to make sure this won’t happen again.

“This year it is dicamba,” Taylor says. “What product is going to be next? It will be hard for ag retailers and farmers to trust a label again. We have to have a process we can count on for an entire growing season.”

Future of dicamba technology

There is a deadline looming in December. At that time, the registrations — XtendiMax, Engenia, FeXapan and Syngenta’s Tavium — will expire.

The recent court ruling does not leave University of Missouri weed scientist Kevin Bradley hopeful for the product labels and current formulations to pass EPA registration.

“I think anybody looking at it would have to say it will have an impact,” he says. “[The court ruling] has got to be in the mind of regulators. It could affect the overall registration.”

However, Bradley says that while it likely will affect some aspects of the product labels, there is a chance for the products to be approved. He says all players in the crop sector are “hoping the EPA makes a decision well before the December deadline so that farmers can plan accordingly for purchases.”

Still, it is uncertain when the EPA will act, and given the latest court ruling, much uncertainty remains. Bradley says that is causing companies to “scramble.”

Companies are trying to place as much of the current dicamba products on as many acres as possible before the July 31 deadline. It also is causing farmers to scramble to find products beyond 2020 if they choose to plant dicamba-tolerant crops. Bradley warns of outlier chemical companies promoting dicamba “alternatives.”

“There are only four products farmers can apply legally over the top of dicamba-tolerant crops,” he says. “Anybody coming to you saying anything else or trying to get some other kind of dicamba product on your crops is outright illegal and disingenuous.”

Bradley says there was a reason for dicamba products such as XtendiMax, FeXapan, Engenia and Tavium; they were brought to market to control resistant weeds such as waterhemp and Palmer amaranth. Turning to products such as Cobra or Blazer will only exacerbate the weed resistance problem that already exists in these species. “They are not going to be as effective,” he adds.

The discussion over the future of dicamba technology remains fluid.

On June 12, Corteva filed a motion to intervene in the U.S. Court of Appeals. According to the company, it was not a party to the lawsuit, and until June 3, the case appeared to involve only the XtendiMax registration.

However, the court vacated Corteva’s registration for DuPont’s FeXapan with VaporGrip technology. The company is attempting to “intervene to preserve our rights and to support the rights of customers to use the impacted dicamba weed control technologies.”

In the meantime, this ruling has put the Xtend cropping system in flux. Bradley says it has other seed companies scrambling to get their product in fields for 2021. “There are other options out there,” he notes.

But as Rowland points out, farmers are dealing with tight margins. “We have enough challenges as it is,” she says. “We need to be able to plant a seed, a system and use a product that works and does not harm others in the process.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like