December 1, 2011

The final subtle nod and the rap of the gavel that signify the winning auction bid are the same as they’ve been for decades, but today’s farmland prices are anything but ordinary.

“We have set all kinds of records,” says Bruce Brock of Brock Auction Company, Le Mars, Iowa. “In the past six months, farmland has taken a good jump.”

Continued record-breaking sales — including two in Iowa this fall that topped $16,000/acre — have heads shaking, tongues wagging and Federal Reserve officials warning of a price bubble ahead. That warning has ag economists, farm lenders and land brokers on the defensive as they explain the economics supporting today’s hot market and the risks that lie ahead.

“This is not a bubble,” says Murray Wise, a longtime farmland broker and auction company owner. “The economics of this [market] are pretty rock solid.”

But the possibility of a speculative bubble is a “nagging concern,” says Purdue University ag economist Craig Dobbins. “Is there potential for a bubble? Yes. Has it started? It’s hard to know. Bubbles are easier to discern after the fact. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be bubbles.”

Double-digit price hikes

Talk of a farmland price bubble has grown as record-breaking sales have accumulated over the past two years. After Midwest farmland prices stalled out between 2008 and 2009, prices began climbing at an escalating rate, culminating in a two-year increase approaching 50% in some areas.

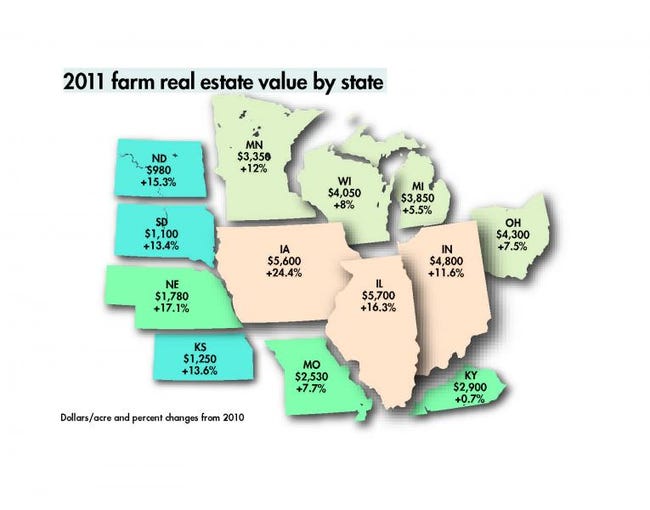

Iowa farmland values, now pegged at $5,600/acre on average, led the pace with a 24.4% increase over the past year. That’s on top of a 16.9% increase from 2009 to 2010, a two-year price hike of 45%, according to a USDA report on farmland values released in August.

Irrigated Nebraska cropland has been up a similar amount over the two-year period. Irrigated cropland was up 23.8% to $3,900/acre from 2010 to 2011, on top of a 16.6% increase the previous year.

Price increases in other Corn Belt states have been lower, but still up double digits over the past year in many cases. These include Illinois, up 16.3% to $5,700; Indiana, up 11.6% to $4,800; and Minnesota, up 12% to $3,350, according to USDA. Farmland value increases have been more moderate in Michigan, Ohio, Missouri and Wisconsin, where they were up by 5.5 to 8%, to $3,850, $4,300, $2,530 and $4,050, respectively.

The double-digit trend extended into the western Corn Belt, where in addition to Nebraska, Kansas farmland was up 13.6% to $1,250; South Dakota, up 13.4% to $1,100; and North Dakota, up 15.3% to $980.

As in recent years, operating farmers continue to be the major buyers of farmland. Outside investors are showing strong buying interest, too, but are largely being outbid by farmers, Wise notes.

“We are in an area where there are a lot of established farmers who are expanding their operations,” Brock adds. “It’s the same old story; you need more land to stay efficient.”

Puncturing bubble worries

Federal banking regulators began warning of a farmland price bubble early in 2011.

Thomas Hoenig, then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, testified in February before the U.S. Senate Agriculture Committee that distortions in capital markets, including historically low interest rates, could lead to a farmland price bubble that could damage the U.S. economy when it collapses.

He warned that farmland prices could drop as much as a third if interest rates return to historic averages.

Since then, the Farm Credit Administration, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Kansas City Fed all have hosted sessions addressing a potential farmland price bubble. Federal Reserve regional bank examiners and the FDIC are focusing more on lending standards and risk-management practices at rural banks.

Ag economists who follow farmland price trends acknowledge there is reason for concern if farmland prices continue to heat up, but they argue that current price levels aren’t in bubble territory.

“There is a bubble somewhere, but it is not farmland,” says Gary Schnitkey, an ag economist at the University of Illinois. “I can see why they are concerned about asset prices going up, but they have picked the wrong market.”

Schnitkey says that current Illinois farmland values are roughly in line with capitalization values, which are calculated by dividing average land rent by long-term interest rates.

Rabo Agrifinance reached the same conclusion in a July report that evaluated farmland values across the U.S. It said that recent land price increases are not linked to speculation or other factors that traditionally lead to a bubble and that strong crop prices and low interest rates support recent price gains.

“Our definition of a bubble is an asset that is not supported by a fundamental value,” says Sterling Liddell, vice president for food and agribusiness research for Rabo Agrifinance.” With the dramatic increase in commodity prices, land values are supported by fundamental values.

“What we are saying from an asset value perspective is not that there is no risk,” Liddell says. “There clearly is risk. But we do not see this as a classic bubble.”

However, if the hot land market continues into 2012, prices could reach speculative heights, Schnitkey says. “If we have another year of 20% increases, you are getting into the speculative area,” he acknowledges.

A drop ahead?

There’s a good chance that farmland values could drop at least modestly in the coming years if interest rates go up or commodity prices fall below trend-line projections of $4.50/bu. for corn and $10.50/bu. for soybeans, as some experts expect.

“We anticipate land prices to fall over the next three to seven years,” says Liddell of Rabo Agrifinance. “Our most clear and present danger is interest rates.”

Schnitkey sees little reason for concern in the short term. “Farmland values could drop, but I don’t see that happening in the near term,” he says. “Commodity prices are hanging in there and interest rates are low. Something pretty dramatic would have to happen to see a 30% drop in land values.”

If interest rates rise after the Federal Reserve’s plan to hold interest at today’s historically low levels expires in 2013, interest-rate bugaboos could come into play.

“If interest rates would go up two percentage points, that would conceptually mean a 30% fall in land prices,” Schnitkey says.

The strength of commodity prices is another critical factor that will determine the rise or fall of farmland values. There’s considerable downside potential as recent high prices attract more resources and higher production, says Dobbins of Purdue.

“If you were a pessimistic person, you could put together a pretty dire scenario of what could happen to crop prices and thus to land values,” he says. “I am absolutely convinced that these high crop prices will result in a worldwide response to increase corn and soybean production. It is fairly likely that supply will overshoot demand.”

Learning from the 1980s

Today’s go-go land market reminds many people of the farm crisis of the 1980s, which was spurred by high commodity prices and rapidly increasing farmland prices beginning in the mid-1970s.

But lessons learned in the ’80s, combined with the strong balance sheets of most farmers, weigh against a similar calamity in the near term, observers say.

“In the 1980s, farmers’ balance sheets had become very laden with debt,” Liddell says. “Today, farmers have historically low debt-to-equity levels.”

Lenders also are wary of a repeat of the '80s. “A number of lenders who are now in management were just getting started in the ’80s,” Liddell says. “They remember what it was like. That is why lending standards have remained relatively conservative.”

“There is no way you can’t remember those times,” says Joel Larson, a loan officer for AgStar Financial Services, a Farm Credit affiliate serving Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin. “It left a mark on many of us. I think it has made us cautious about how we approach financing in this market.”

To reduce loan risks as land values have heated up, AgStar has begun basing loan amounts on the ability of a typical rental rate for a parcel to cover the payment. A number of farm financial ratios also are evaluated in developing a final loan package, which typically is amortized for more rapid payoff as the amount of debt increases, Larson says.

With many farm purchases now being made with hefty down payments, there’s generally far less financial risk from a drop in land values compared to the 1980s, says Brock, the Iowa land auctioneer.

“There are a lot of people leveraging 50% or less for these farms, or even paying cash,” he says. “If there was a 30% drop, it wouldn’t affect most farmers all that much.”

A University of Illinois stress test on the impact of a 30% farmland price drop concurs. It shows that the average Illinois farmer’s debt-to-asset ratio would increase only modestly from 0.24 to 0.27 with a 30% land price decrease. However, younger, more leveraged farmers would be at more risk, with debt-to-asset ratios likely to increase from 0.30 to 0.45.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like