Obtaining a loan often requires collateral such as real estate or equipment. That’s tough for beginning farmers who don’t own enough assets to leverage and often rent most of their crop acres. Bill York says there is still a way for this next generation to obtain funds to farm.

“Our security is the crop itself. We don't take security in the real estate or the equipment. It's focused entirely on the crop,” says York, FarmOp Capital executive chairman. “Our loan is based on the farmers’ ability to produce the crop, crop insurance and a marketing plan.”

In its fourth year, FarmOp Capital uses a production-based lending approach — focusing on farmers who are growing significantly, rent a significant part of their land or are just starting out. York says the problem for borrowers who fall into any of these categories is the owned real estate to operator real estate often does not meet traditional metrics. “But that is also the farmer that is growing in the largest segment right now in terms of row crops,” he says.

FarmOp Capital offers a structured loan product that allows each crop year to stand on its own. The company looks at the farmer’s marketing plan, crop plan and crop insurance to determine the overall crop value resulting in the final loan amount.

New way of lending

York says farmers can benefit from this type of nontraditional farm loan in these ways:

Early approval. York says FarmOp Capital approved 2022 growing season loans as early as October 2021. Just last year, 63% of existing customers renewed their operating loans in that time frame. “The advantage is the farmer had certainty in terms of its funding source and was able, especially this year, to lock in inputs, lock in rent and be able to manage his operation more effectively,” he says.

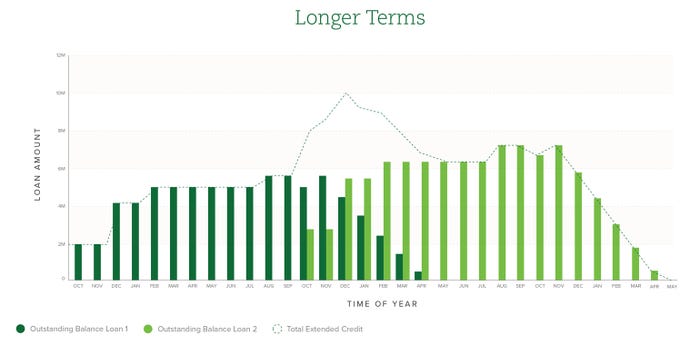

Length of loan. A FarmOp Capital loan can stretch up to 24 months. Traditionally, these types of operating loans stop around 16 months. “That allows the farmer to go through a natural marketing cycle,” York says. With revolving loans, farmers generally need to sell the crop to buy inputs for the next crop. FarmOp Capital loans can even overlap.

CONSTANT COVERAGE: FarmOp Capital offers loans that can run through 24 months, often allowing farmers to have constant coverage from planting to marketing of a crop as depicted in this chart.

Expansion opportunity. Since FarmOp Capital lends on the crop itself, as the value of the crop changes, loan amounts can expand. York calls it the “accordion feature.” For instance, this year while crop prices increased, so did input costs. This feature, coupled with the fact that FarmOp Capital loans up to 100% of input costs for the crop, gives farmers the option to pay cash for inputs. “It also allowed them to negotiate the best rents, because they can pay earlier,” York says.

This also allows flexibility for established farmers who find another 200 acres of land to rent, and they need more money for additional inputs. “We could immediately adjust to cover that,” York adds.

Fixed rate. Loans rates are locked in for the life of the loan. That is key as interest rates continue to climb, York says. “We have farmers with loan rates that have been locked in since last October, and they will run up to 24 months. That’s a huge advantage to reducing the overall finance costs of that operation.”

The results

FarmOp Capital is available in 21 states, appealing to both seasoned and young farmers.

In just the past four growing seasons, York says farmers borrowing with FarmOp Capital grew their operations about 6% in acreage over the previous year. He’s excited by the increased interest by the next generation of farmers.

“They want to start their own operation,” he notes. “They don’t want to be tied to their parents signing for them or providing additional collateral. We can lend to them, and we don’t need those guarantees. That is an important part of moving agriculture forward.”

Read more about:

Next GenerationAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like