August 24, 2022

A settlement barn, circa 1830, sits on a unique farm in Preble County, Ohio. Besides the tillable farmland, the farm also encompasses a limestone quarry — operational until the early 1920s.

Foundation stones for the barn, house, spring house, flagstones and sidewalks were quarried from this outcrop of limestone. The remains of two lime kilns found on the property were used in the production of agricultural lime.

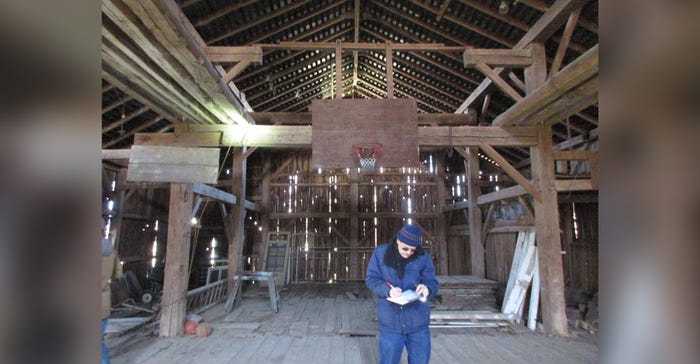

The 1830 barn is a raised-bank barn with double forebays. It is not unusual to see cantilevered forebays on the front of barns to protect stable walls, but to have a forebay on the back, or driveway side of the barn, is unusual. The back forebay protects the foundation from the freezing and thawing of the earthen ramp, and sometimes is used for housing hogs or sheep.

Massive posts and beams in the timber frame display a high quality of hewing — very smooth. The braces are up-and-down sawn by a water-powered sash saw, one of the indications the barn was built before the Civil War.

Evidence of “snap” is present. When a slow water-powered saw finishes sawing a board, it stops within an inch or so from the end of the log. The log and board are returned back to the starting point, at which time the sawyer pulls on the board and snaps it off. The log is then moved over and set for the next board.

The peak of the roof has a wooden hay track for unloading long hay from the wagon to the top of the haystack. This barn was built long before the hay track was invented. When it was discovered, it was difficult to get the loaded hayfork over the crosstie.

The farmer’s answer was to cut out the crosstie without realizing how badly he was weakening the structure of the barn. In this case, the scaffold tie was left in place, doing the duty of the missing crosstie.

A hay hole in the bay to the right of the threshing floor is unique. It is a one-of-a-kind, hand-riven cage from high in the mow to a hole in the mow floor to enable gravity feeding of livestock in the basement from the top of the haystack.

The board-on-board threshing floor is 22 feet wide. While threshing on the threshing floor, the large driveway doors at one end of the threshing floor and an opposite set of wind doors on the other end are set to create a wind tunnel, providing just enough breeze to blow away the chaff and let heavier grain fall to the floor.

The double flooring prevents the grain from being wasted by falling through the cracks. Likewise, waste walls along each side of the threshing floor, and thresholds at doors, protect against the loss of grain.

All the posts have raising holes either on the front or on the sides. During the raising of the barn, very long raising poles are spiked into the raising holes. As the bent is raised, the raising poles drag along the ground. If the bent begins to fall, the raising poles act as braces or brakes to keep the bent from falling and injuring the workers.

Larry Snyder’s great-grandfather, Mahlon Snyder, purchased the 94-acre farm in 1899, and it remains in the Snyder family today. It is a Century Farm. Sometime between the purchase of the property and 1923, he added the straw shed to the barn. He then built the double corncrib that stands nearby.

When the interstate highway went through in the 1950s, a portion of farmland was taken for its construction. Now, the 66-acre farm produces corn and soybeans.

This barn has had a long and distinguished past, and thanks to the stewardship of the Snyder family, it will stand and serve for years to come.

Gray is the Lady Barn Consultant. Contact her for barn consultations or to purchase the book “Ohio Barns Inside and Out, with the Barn Consultant.” Email her at [email protected] or call 740-263-1369.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like