June 2, 2014

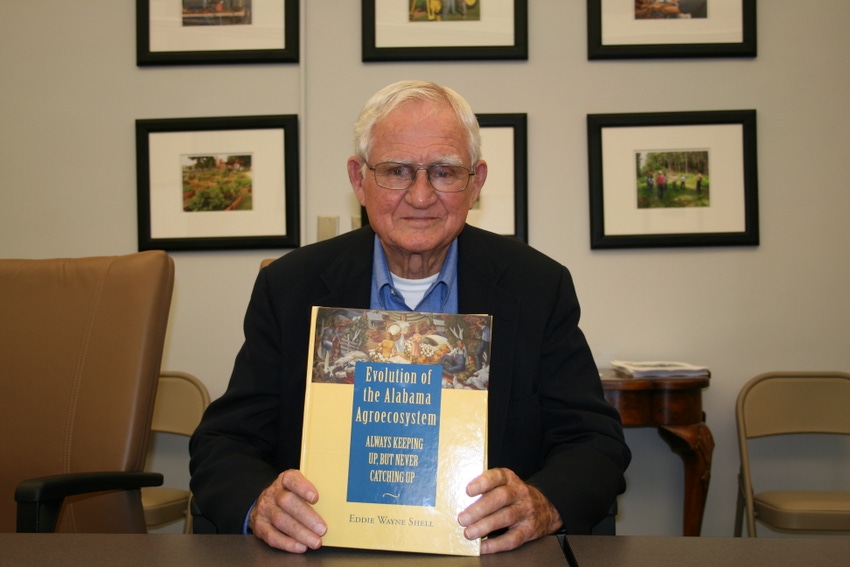

It’s always difficult to turn a critical eye towards something we love, but Wayne Shell – a retired Auburn University professor who once chaired the school’s Department of Fisheries and Allied Agriculture – has done just that in a revealing new book, “Evolution of the Alabama Agroecosystem: Always Keeping Up, Never Catching Up.”

The book is the culmination of 20 years of studying Alabama agriculture, and it’s far from being this year’s “feel-good” read for the state’s farming interests, nor was it intended to be. Try as it might, Alabama agriculture has never caught up, and there are some tragic and intractable reasons why, Shell argues in his book.

Some 30 years ago, Shell and other Auburn University faculty members were enlisted by the College of Agriculture and the Alabama Cooperative Extension System to guide Alabama farmers through one of the bleakest farm crises on record in the mid-1980s. Their job was to help as many financially stressed farmers as possible transition to alternative forms of agriculture — Christmas tree farming, fish farming, leased hunting —anything other than conventional farming.

“It was obvious U.S. agriculture was in serious trouble, but the situation in Alabama was even worse,” he recalls.

Shell, a professor emeritus who capped his 35-year Auburn career chairing the Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures, began to investigate the reasons why Alabama agriculture was so adversely affected by the economic downturn.

What he learned shocked him. Alabama agriculture was not only uncompetitive with the rest of the nation but has been from the beginning of its history — and even in the areas long considered to be the state’s strengths: annual corn and soybean yields, dairy output and cropland rents.

Unable for several reasons to investigate these concerns at the time, he vowed to himself that he would pick up the trail after retirement.

He was true to his word. Last year, New South Books published his findings, the culmination of almost 20 years of intensive, multidisciplinary study that leaves no stone unturned. Shell started with the more obvious factors — history, physiography, soils, geography and climate — but in time, his studies led him to investigate more subtle factors, such as politics and even ethnic influences.

For example, Alabama’s unusually warm and moist climate strike most people as an unqualified plus, but it’s highly erratic.

“We are prone to one to three weeks of unusually dry weather during the middle of the growing season, and that wouldn’t be as much of a problem except for the state’s poor soils,” he contends.

Another limiting factor stems from the fact that virtually all of the principal crops produced in Alabama — cotton, soybean, corn and livestock — evolved in other parts of the world. In fact, the only two Alabama commodities that originated in the state are loblolly pines and catfish, Shell stresses.

Even political factors figure into these challenges, he maintains. At the top of the list are what Shell describes as the “Southern Band of Brothers”—a tightly bonded multigenerational coalition of Southern congressmen and senators who have fought fiercely to safeguard Southern agricultural interests.

This coalition was instrumental in ram-rodding through Congress the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which provided permanent protection for what Shell describes as the five “Southern belles”: cotton, peanuts, tobacco, rice and sugarcane. He contends that this legislation worked to fuse Alabama’s economic destiny permanently with agriculture at a time when the state would have been better off pursuing another destiny, namely industrialization.

Alabama’s historic economic struggles

Having demonstrated to his satisfaction that Alabama agriculture was poorly competitive, Shell turned to an even more disturbing possibility: that the state’s poorly competitive agriculture had contributed to the evolution of a poorly competitive general economy. Data published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis showed that on a per-capita basis, the state’s gross state product (GSP) was among the lowest in the nation and had been from the time such data was first collected.

Shell attributes this poor economic performance to limited capital accumulation that had occurred with the early stages of Alabama agriculture. “It seemed to me that Alabama farmers had spent too long in the human and animal power stage of agriculture before entering the mechanization stage and ultimately the industrial and post-industrial stages,” he says.

Shell also points to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, which reveal that at the beginning of the 21st century more than 90 percent of Alabama farm household income came from off-farm sources, a significant amount of which was derived from federal subsidies.

Alabama’s ethnicity has also played a role in this tragic saga, Shell contends. Like so many Alabamians, much of Shell’s heritage traces back to the frigid, craggy hills of the Scottish highlands. “They were cattle people — much of their income came from grazing cattle, which they supplemented by raising oats,” he says. This represented the barest form of subsistence agriculture.

Ten of thousands of these hardscrabble Scottish farmers were driven off their farms by the English after the Battle of Culloden in mid-1700s. Many, if not most, of these displaced farmers eventually found their way into the Southern Back Country, weaving their preference for personal freedom, subsistence farming and resistance to change into the cultural fabric of Southern agriculture, only complicating an already intractable geophysical situation.

“We have little choice but to play the hand that we were dealt, namely the state’s physiography, climate and soils that have partly placed us at such a disadvantage,” Shell contends.

Shell says there is no prosperous economic future that does not pass through the agricultural stage, the industrial stage and, finally, into the post-industrial stage of socio-cultural evolution.

“This doesn’t mean that there is no place for agriculture,” he stresses. “But it must mean an agriculture that carries its own weight and that contributes its fair share to the state’s social and economic progress.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like