October 13, 2014

Editor's note: This article has been updated as of 10/14/14 to reflect an attribution change on the chart shown below. The research was conducted by USDA.

Many people have wondered if harvesting corn stover as a cellulosic ethanol feedstock can be sustainable. Now that cellulosic ethanol producers like DuPont Industrial Biosciences and POET-DSM have several years of testing under their belts, it appears that not only is partial harvest sustainable, it also contributes to a better seedbed and yields the following year.

POET-DSM perspective

This summer, POET-DSM announced that five years’ worth of soil nutrient data gathered at its Project LIBERTY site in Emmetsburg, Iowa, showed biomass harvesting is consistent with proper farm management. POET-DSM is scheduled to begin producing cellulosic ethanol from corn stover on a commercial scale this fall, gradually climbing to a production capacity of 25 million gallons per year. The soil research study was conducted by Douglas Karlen, USDA Agricultural Research Service; Stuart Birrell, Iowa State University BioSystems and Agricultural Engineering Department; and Adam Wirt, POET-DSM.

The researchers studied soil quality under different biomass harvest scenarios at the site. Their data have been aggregated with 500+ years of additional soil data from four separate sites. The researchers found that stover harvest can be sustainable on fields with slopes of less than 3% with consistent grain yields of at least 175 bushels per acre. Nitrogen and phosphorus applications should not need to change when harvesting stover at one ton per acre, but the researchers did recommend that farmers monitor potassium.

Jim Wirtz, his two brothers and his son farm 3,000 acres about 12 miles east of Project LIBERTY. They also raise hogs and own a commercial feed mill. The Wirtz family has been involved in the stover harvesting project with POET-DSM since its inception. They did so at the suggestion of Jim Wirtz’s other son, Adam, who tragically lost his life in a farming accident last year.

With increasingly high planting populations (the Wirtzes plant corn at an average of 38,000 plants per acre in a corn-on-corn rotation) and stacked trait hybrids producing increasing amounts of biomass, corn residue was becoming a bigger hindrance to tillage. Soil in the spring also took much longer to warm up with heavy residue. So, when POET-DSM was looking for farmers to supply corn leaves and husks, Adam suggested that the Wirtzes look into harvesting stover.

Jim’s nephew had a Vermeer round baler and began harvesting, removing about 25% of the residue. “We leave the stalks in the field,” Jim says, adding that his nephew can bale 150 bales per day on average. He also harvests stover for two other farmers supplying feedstock to Project LIBERTY. The Wirtzes have an accumulator that can pick up about 80 bales per hour which they take to the edge of the fields to be loaded on to their drop deck trailer. The lower profile of this trailer facilitates loading, Jim says. He stores the bales for March delivery to the ethanol facility. The trailer can transport 36 bales at a time. Once bales are picked up, the Wirtzes go into the field with a disk ripper.

Financial incentive

In addition to farming, Jim Wirtz is an ag lender. With corn currently averaging $3.50 per bushel, earning another $40 per acre for stover can mean better margins. When corn was at $7.00 per bushel, the incentive to bale was not as appealing. “I think stover will play a bigger role now at these lower corn prices,” Wirtz says. Area farmers selling stover to POET-DSM currently receive $72-$77 per bone dry ton.

“We’ve seen better emergence after removing some residue. We’ve also seen the most benefit on acres where we’re growing some organic corn,” Wirtz says. This is because rotary hoes or harrows used for managing weeds in organic production work more easily in fields with less residue. It also should be pointed out that manure from the hog operation supplies a good share of the fertilizer for the entire crop operation. Wirtz started out slowly with the project and has since increased the amount of biomass harvested. If the market continues to expand, he would recommend that other growers at least take a look at harvesting biomass if their soils have good fertility and if they are in close proximity to a cellulosic ethanol plant. More biofuel producers could be licensing the cellulosic ethanol technology.

Many of the growers supplying biomass to POET-DSM use the EZ Bale system which removes less of the cornstalk than conventional stover collection. The bales are made by disengaging the residue chopper/shredder on the grain combine. The material that comes out of the back of the combine is formed into windrows. By laying windrows, the operator does not have to rake or chop the biomass. After a couple of days, windrowed material can be baled, explains Adam Wirt, director of biomass, POET-DSM. Many growers use round balers because of their lower capital investment compared to square bales, he says.

About 75% of the growers supplying biomass bale it themselves while the other 25% hire custom balers, Wirt says. Some growers have the extra labor available to do this in addition to their other fall farming operations and some growers have bought balers together. “There is a $2-$5 per ton price advantage for growers to do the baling themselves,” Wirt says. Many of these farmers also have flatbed trucks and make their own deliveries.

DuPont Industry Biosciences Project

DuPont Industrial Biosciences also worked with Iowa State University, studying eight fields in 2012 and six fields in 2013, all within a 30-mile radius of the DuPont biorefinery in Nevada, Iowa. The facility is expected to begin cellulosic ethanol production later this year. DuPont and Iowa State determined that partial (about 50%) corn stover removal improved corn yields by about 5.2 bushels per acre in more than 90% of the fields studied.

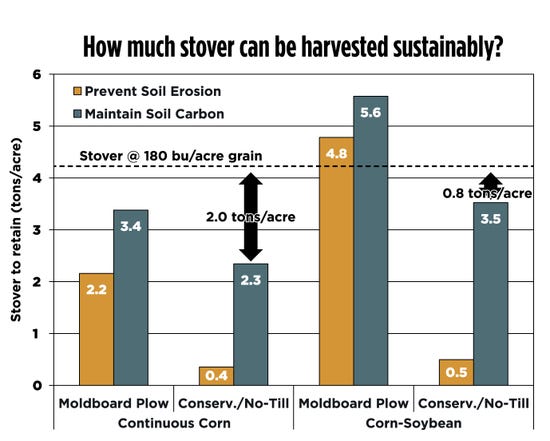

Source: USDA

Several growers in north central Iowa will supply stover to the DuPont facility, which will have a nameplate capacity of 30 million gallons per year when construction is completed.

DuPont will annually collect 375,000 tons of stover from approximately 190,000 acres. John Maxwell, a grower who has supplied stover to the project since 2012, says there are several benefits of partial stover removal: reducing tillage (and associated labor and fuel costs), warming the soil for spring planting, reducing the number of overwintering insects and improving corn yield. Maxwell applies hog manure on the corn to improve organic matter levels.

In a webinar hosted by Biofuels Digest and in an article featured here in July, Andy Hegenstaller, agronomic research manager, DuPont Pioneer, showed chart you find with this story that illustrates how much stover should be retained in fields to prevent soil erosion from exceeding tolerable levels. Developed from several years of USDA studies, the chart shows that tillage practices and crop rotation both have significant effects on how much stover can be harvested sustainably. A two-ton per acre harvest would be sustainable for continuous corn production. In a corn-soybean rotation, Hegenstaller said that the frequency of stover harvest should be reduced.

Hegenstaller pointed out that fields averaging 170 bushels of corn per acre would produce about four tons of stover per acre. Fields averaging 210 bushels per acre would produce about five tons per acre, and fields producing as high as 295 bushels of corn per acre would translate to about seven tons per acre.

Tim Fevold, accredited farm manager, Hertz Farm Management, Nevada, Iowa, oversees the management of approximately 70 farms in north central Iowa, a dozen of which have been involved in the DuPont project. All are row crop farms with no livestock, although hog manure is spread on a couple of the operations. Most are in a corn-soybean rotation on Clarion-Nicollet-Webster soil. The stover is collected from relatively flat fields.

“I would encourage anyone who has the right soils, topography and fertility to take a look at harvesting stover,” Fevold says. Never more than 50% of the residue is taken off these fields which have an average yield of 175 bushels per acre and up.

DuPont contracts with third parties to do stover harvesting while POET-DSM contracts with third parties or farmers themselves. Fevold says that he would prefer a third party to handle the work. “Farmers have a lot of other tasks, like fertilizing and tillage, in the fall and may not want to invest in the equipment needed to do stover harvesting.”

Harvesters offer perspective

Two farmers talk about their experience working on the DuPont biomass project.

Brad Plunkett, Plunkett Farms, a custom harvester from Maxwell, Iowa, has worked with the DuPont program since 2012. He has harvested stover on 35 participating farms, and his crew will harvest approximately 7,500 acres this fall. Plunkett has farmed for 25 years and established his custom harvesting business in 2012 as a result of the DuPont program. “Custom harvesting has enabled me to continue farming,” Plunkett says, noting that diversifying also has enabled his son to join him in the farming business.

DuPont has supplied the equipment for the project. Plunkett’s crew has had experience with AGCO, Krone and New Holland balers; several main brand tractors; and Hiniker windrowers and stalk shredders. The crew also has used a stacker developed by Morris Industries’ ProAg that can stack 12 bales at a time. This 16K Plus Auto Align® Bale Runner enables bales to be oriented in any position and allows one person to stack 80-120 bales per hour.

A healthy field of biocellulose ready to head to the ethanol plant for production will be a more common site in the future as farmers seek more profit opportunities. Photo by Poet-DSM

The bales are then driven to a central location at the edge of roadsides to facilitate pick up by semi-trailer trucks. These trucks, which also operate under separate contracts with DuPont, transport the bales to the biorefinery. Each semi hauls 36-39 bales per load. To reduce transportation costs, Plunkett creates dense 3 x 4x 8-foot bales weighing between 1,300-1,500 pounds. They yield about 1,000 pounds dry matter.

The main challenge that the custom harvester faced was during the first year of the project. “When we tried to make bales denser, the twine broke and had to be cleaned up after the crew went through the field,” Plunkett explains. This has since been remedied with higher quality twine.

Piling up bales

Andy Moser, Nevada, Iowa, has provided custom harvesting for silage customers for about 15 years, and also started harvesting stover for the DuPont project in 2012. Wet fall weather can be challenging, particularly as crews have just about 15 days to bale stover after grain has been combined, he says. “A rain event can reduce that time to as little as five days.”

Moser has worked with Hiniker windrower shredders (putting two 20-foot units together) and Hesston and Challenger big balers to produce high density 3 x 4 x8-foot bales that will yield 1,000 pounds of dry matter. Last year, Moser paid a bonus for producing 500 bales in a 24-hour period. “The record is 750 bales from one operator, one baler,” he says, adding “My whole crew can do 2,500 bales in one day.” Moser also uses the ProAg stacker. Each stover harvest crew is made up of two windrowers, two balers and one stacker.

Moser has observed agronomic benefits of partial harvest, noting that reducing stover helps reduce nitrogen tie-up. “Seed comes up more quickly because the seedbed is warmer. Farmers love the benefits of stover removal in the spring,” he says.

Some of the farmers on whose fields Plunkett has worked have tested stover removal. “You can tell right to the row the following spring where stover was not removed. Not harvesting some of that stover had a negative impact on emergence,” he says.

Kevin Gerlach, a corn grower from Nevada, Iowa, has been working on the stover project since its inception. Like many of the area farmers, he has a corn–soybean rotation and farms on Clarion-Nicollet-Webster soil. He advises raising the shredder if there is concern about taking off too much residue. “Farmers should look at the science-based data, not just rely on their intuition. Over time, you’re not losing organic matter if you are only taking off one to two tons per acre. Each operation is different, give it a try,” he says.

Farmers working with DuPont can earn an average of $9 per bale (higher or lower depending on incentives, including early sign up, commitment to a minimum number of acres, early harvest, etc.).

Gerlach says, “I hope the [cellulosic ethanol] industry takes off. It benefits farmers and their local communities. It brought a lot more industry to Nevada.”

Supplying stover for the cellulosic ethanol market is a great opportunity for corn growers, custom harvesters, truckers and equipment dealers to name a few, Plunkett says. However, he acknowledges that the industry’s future still depends a great deal on decisions regarding the biofuel volume requirements in the Renewable Fuel Standard. This said, Plunkett believes that the corn stover market will continue to provide good opportunities in central Iowa, where ethanol production is big business.

Hertz Farm Management’s Fevold agrees that the future of the RFS is a concern. “If they repeal it, this could derail cellulosic ethanol. It needs a fair opportunity in the market. I’m frustrated that the public thinks that the RFS is a subsidy for biofuels. It’s not,” he says.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Farm Industry News Now e-newsletter to get the latest news and more straight to your inbox twice weekly.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like