If we were playing by the rules of supply and demand, consumers would not be paying $9 or more per pound for hamburger. But we are in a COVID-19 world, where beef producers are ready to deliver animals, but all those cattle cannot be slaughtered.

Wesley Tucker, University of Missouri Extension agriculture business field specialist, says that consumers need to realize that while there is no shortage of beef, there is a shortage of meat.

“A lot of people are talking about if you go to restaurants or grocery stores, there are certain beef items you can purchase or certain ones you can’t,” he says. “And that is why we are starting to see $9, $10 a pound on hamburger.”

Related: Complete coronavirus coverage

Buildup of beef

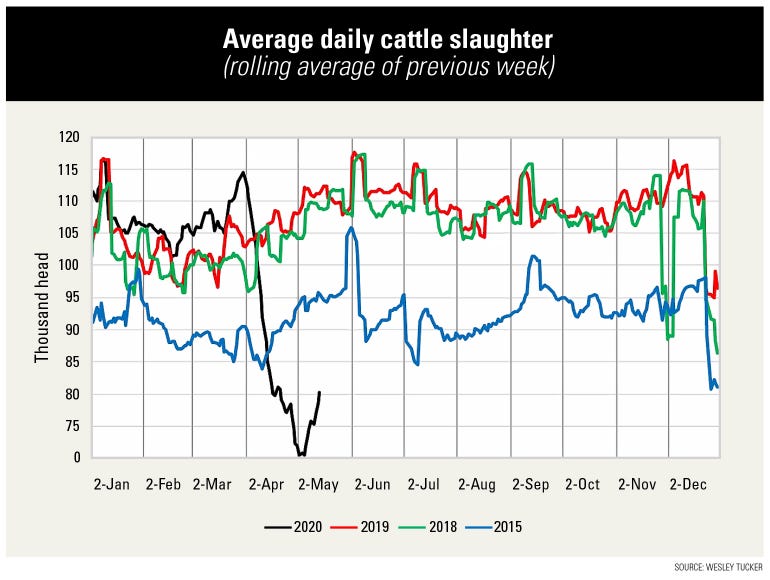

There is plenty of beef supply in America. When the coronavirus first came to light in late March, cattle slaughter remained at capacity. Tucker says that they were harvesting 115,000 head per day, trending above the averages of the past two years.

At that time, the agriculture industry was deemed “essential,” and meatpacking plants continued to harvest animals to keep food flowing to Americans.

“I think plants really saw what was coming as COVID started to spread from the coast inward, and they really tried to ramp those packing plants up just as hard as they could,” Tucker explains. “They were getting up to 675,000 head a week, pushing those plants for all they were worth.”

Then COVID-19 moved into the Midwest. Processing plants workers started get sick. Some could not come to work; others did not show up to work because of fear of catching the virus. And in one month, slaughter dropped to 70,000 head per day on average.

“You can just see how that black line just dropped like it’d fallen through the ice on a frozen pond,” Tucker says.

Now, the problem is there is a huge supply of cattle ready to go to the packing houses but cannot. “If we could turn this right back to full capacity today, we still be about 600,000 head behind,” Tucker says.

While the average daily cattle slaughter recently rebounded a bit, he warns that if packing plants keep on their current progression, there still is “easily 1 million head of finished cattle backlog.”

A glut of cattle across the country are in a holding pattern, so the beef supply is strong. Still, the early shuttering of packing plants coupled with the slow recovery is resulting in fewer animals slaughtered. That is causing a meat shortage.

Hold the meat supply

Consumers may wonder why cattle producers cannot just ship less cattle or produce less calves, effectively reducing the supply of beef.

Typically, cows in the U.S. calve either in the fall or spring months, and some beef farm operations have both. When the coronavirus hit, fall calves already were being fed in feedyards or pastures, and some cows were on the verge of giving birth.

While a few producers feed out their own cattle, others deliver them to a feedyard to grow them out. With packing plants shut down or at reduced harvest capacity, these feedyards had to keep the fed cattle, or those ready for harvest, in their pens — which in turn meant they were not buying any additional feeder cattle from farmers.

Placements for feeder cattle in feedyards was at an all-time low in March, down by 23% from last year, Tucker says. He adds that April numbers will be down as well — maybe not quite as much — but they will be down.

“We have a lot of cattle here in May that are coming off warm-season pasture that are having to find a home,” he explains. “They're having to compete with all of this backlog of finished cattle that aren't leaving yet. So, that is kind of creating a problem.”

Now beef farmers are trying to find a place to market fall-born calves, and some are trying to figure out what to do with spring-born calves that will be weaning in a few months.

Tucker says as the industry starts to see packing plants back up and running, there still is uncertainty as to what levels they will return — full or partial capacity. If at less capacity, it is likely calves will remain on the farm. More cattle supply without a place to slaughter results in more beef, less meat and higher prices for consumers at the grocery store.

Farm price expectations

Tucker saw some “optimism” in the markets during mid-May. “Prices have improved at our larger auction markets,” he says. However, the real question is what happens long term.

Even if processing plants can work through the beef backlog, Tucker says beef producers should be realistic about prices. “Prices are probably going to go down for finished cattle going forward," he says.

A good scenario for Tucker is one where people get back to work, and there is a surge of people wanting to get back to their daily lives, eating a lot of meat and prices rebound. In that case, he says, beef producers will do really well on the price side.

On the other side is the possibility that COVID-19 returns in the fall, and peoples' jobs shut down again, or restaurants are shut down, and beef demand is lost.

“There’s some chance the [beef cattle] prices could go down,” Tucker says. “I hope they don’t, but there is a scenario out there where prices in 2020 don’t get back to where they were prior to COVID-19.”

He says that beef producers should make a plan for the worst-case scenario. “Make sure you’re watching your costs, and make sure you’re planning with your herd,” Tucker warns. “And then don't just hold out to hoping these prices get back to where they were prior to COVID.”

Read more about:

Covid 19About the Author(s)

You May Also Like