It’s been two months since highly pathogenic avian influenza was reported on a commercial turkey operation in Indiana.

Since then, the virus has spread to commercial poultry operations in 13 other states throughout the Upper Midwest, mid-Atlantic and North Carolina, with most cases reported on turkey operations. More than 100 cases have been reported on commercial operations, and millions of birds have been eradicated because of the HPAI outbreak.

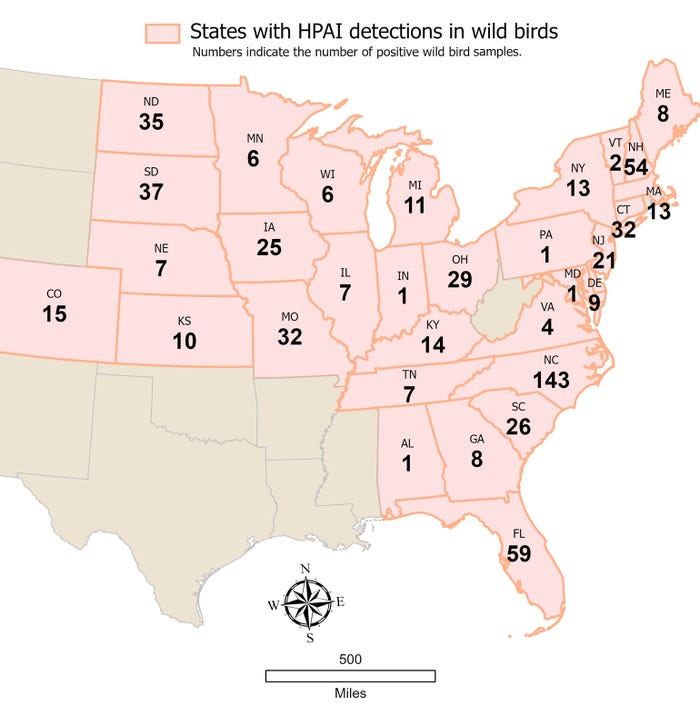

Andy Bowman, a doctor of veterinary medicine at the Ohio State Animal Influenza Ecology and Epidemiology Research Program, says he is alarmed at the geographic spread of the current H5 strain, particularly in wild birds. According to USDA data, the strain has been reported up and down the East Coast, and as far west as Colorado.

“In the U.S., we've kind of interestingly not had the situation where high-path is being maintained in the wild birds for this long,” Bowman says. “If we look at 2014-15, yes, there were wild bird detections initially, but ... it kind of died out in the wild birds, and then once it died out in the wild birds we were able to control local spread within the poultry operations. We were able to get it out of the U.S. poultry flock.

“I think from that standpoint, it's going to be a major issue to see how it behaves in the wild birds, and I think how it goes in the wild birds will end up having a major influence on how it ends up going in the poultry sector.”

So what makes this virus unique, where did it come from and has the poultry industry responded well enough? Here’s what Bowman had to say:

Where are we with this virus at this point? We're certainly at a point of significant concern based on the number of detections we're finding and the geographic spread of those detections. It's kind of remarkable how many states are involved at this point, and the variety of production systems we're seeing in those detections. And I think that's distinctly different from what we've seen in many of the other HPAI introductions where we've seen … not much geographic spread in a particular area, or we find it in a particular production system.

This seems to be from small backyard holdings all the way up to large commercial production systems. We've seen all bird production types involved, so layers, broilers and turkeys. It's a rather interesting situation that we're seeing such a wide net being cast on this one.

Where did the virus come from? Certainly we have strong evidence that we've seen intercontinental movement of the virus from Europe and Asia to North America. And so, probably wild birds are certainly playing a large role in it. But at some point, it becomes difficult to tease out some of those whether it's regional spread or we've had an introduction somewhere within a production system, those sorts of things. So, I think it's certainly been driven via the wild bird route, but certainly humans have contributed to some at least local spread.

Is there something uniquely different about this virus and its ability to spread? That's a very valid question we're going to have to get our hands on. I don't think we have a valid answer to that at this point in time, and there is a lot of genetic diversity in Type A influenza viruses, and it's harder to find out root causes of why a virus does what it does. There are almost 10,000 species of birds, and the virus doesn't behave the same in each, so there are a lot of a factors that would have to be studied to really figure out what exactly is going on.

Are these types of viruses seasonal? It's hard to predict what this virus is going to do, whether that's in the wild bird population or as we look at introductions into domestic poultry. Certainly there are seasonal differences when we look at low-path avian influenza viruses in wild waterfowl.

Now whether HPAI will follow that same pattern or not, it's really hard to say. In general, we seem to have fairly high prevalence in low-path in wild waterfowl in late summer as we have juvenile, newly onto-the-scene birds that haven't been exposed to flu viruses, and they seem to kind of become exposed, become infected, so we see high prevalence then.

And then it diminishes through the winter and spring. Clearly, that's not the situation we're seeing right now, but we also don't have an exact time of when this virus was introduced into North American waterfowl.

How do you think the poultry industry has responded to the situation? I think they have responded as best they can given the situation. I think given our previous introductions, whether it's 2014-15, really has given the industry a chance to prepare and lots of those plans have been written and have been tested. Here were seeing a lot of those plans implemented. And so the fact that they've had plans that have been tested, I think speaks a lot to the preparation the industry has had, so I think the response has been pretty much what to expect given our previous experiences and plans that have been drafted.

What we don't know is that if it's spreading in wild birds, will it run out of susceptible hosts or will it become endemic within the wild bird population? It's a new virus to North American waterfowl, and so we really don't know how it's going to behave, what's going to happen.

Once it's under some immunologic pressure, will it change? It's really hard to know what's going to happen.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like