October 12, 2016

In the Upper Midwest, winter is a fact of life. It is common to see severe cold temperatures, dangerous windchills and abundant snow. Good winter management practices contribute to healthy and productive cattle, reasonable feed costs, and humane care.

Energy needs jump

Beef cattle adapt to colder temperatures during gradual changes in the season by growing longer hair, changing their metabolism and hormone secretion, and depositing insulating subcutaneous fat if the energy level in the ration allows.

Beef cattle increase body heat production as a response to severe cold by increasing their metabolic rate, and as a result, they need more energy and nutrients during cold weather to meet maintenance requirements.

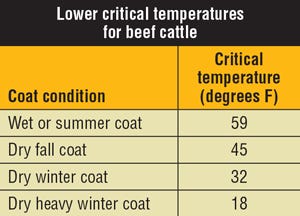

Just exactly when does a cow begin to feel cold stress? The point of cold stress, or lower critical temperature, depends in large part on the amount of insulation provided by the hair coat. As shown in the table below, the insulation value changes depending on the thickness of the hair coat and whether it is dry or wet.

The lower critical temperature is the temperature at which maintenance requirements increase to the point where animal performance is affected negatively. A general rule is that for every degree the effective temperature is below the lower critical temperature, the cow’s energy needs increase by 1%. For instance, if the effective temperature is 17 degrees F, the energy needs of a cow with a dry winter coat are about 15% higher than they would be under more moderate conditions. That energy requirement jumps up to about 40% higher under those conditions if the hair coat is completely wet or matted down with mud.

Lower critical temperature for beef cattle

There are some management considerations to keep in mind regarding changes in feed intake in response to cold stress and the cow’s need for more energy.

• Make sure that water is available. If water availability is restricted, feed intake will be reduced.

• If feed availability is limited either by snow cover or inaccessibility to hay feeders, the cattle may not have the opportunity to eat as much as their appetite would dictate.

• The ration has to be of the quality level that the cow is able to eat enough to meet nutritional needs.

• Be careful providing larger amounts of high-concentrate feeds. Rapid diet changes could cause significant digestive upsets.

Protection from wind

A clean, dry hair coat and protection from the wind help cattle tolerate cold temperatures.

Wind and moisture make the effective temperature (the temperature felt by the body) lower than the temperature on the thermometer. Windchill must be included when calculating the amount of degrees below a cow's critical temperature point. For example, a 10-mph wind at 20 degrees has the same effect as a temperature of 9 degrees with no wind. If the temperature drops to zero (or the equivalent of zero, with windchill), the cow’s energy requirement increases between 20% and 30% — about 1% for each degree of coldness below her critical temperature.

Mud can also reduce the insulating ability of the hair coat. The relationship between mud and its effect on energy requirements is not as well-defined. Depending upon the depth of the mud and how much matting of the hair coat it causes, energy requirements could increase 7% to 30% over dry conditions. In addition, research suggests mud may be associated with decreased feed intake.

Using adequate bedding to keep cattle dry and clean, in addition to providing them with shelter from the wind and a place to stay dry, will help the cattle cope with adverse weather. Make sure whatever shelter you have is correctly ventilated to minimize the risk of respiratory problems from bad air quality.

Remember that cattle can adapt to short-term weather changes relatively well without a significant impact on performance. A cow can deal with a few cold, miserable days without suffering long-term effects. However, ignoring the energy costs of long-term cold stress greatly increases the risk of problems down the road during calving and subsequent rebreeding performance. Any steps that can lower cold stress, such as providing wind and weather protection, help the cow reduce her maintenance requirements.

More information is at the Wisconsin Beef Information Center.

Halfman is the Monroe County Extension agriculture agent.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like