Open-mouth breathing and restlessness. These may seem like symptoms of a common summer cold in humans, but add in a little drooling, and for cattle it is a sign of heat stress.

As summer temperatures tick higher on the thermometer, University of Missouri beef specialist Eric Bailey said cattle producers need to pay attention to the signs of heat stress in their operations. And too often they are overlooked, resulting in cattle losing weight, cows unable to breed or worse — death.

The problem for cattle is with their anatomy. Cattle are similar to dogs, Bailey said, in that they do not dissipate body heat through sweating. Instead, they pant. It affects cattle in two different ways, causing either acute or chronic heat stress.

When they become too hot and cannot get cool, cattle are at risk of acute heat stress, which can result in death. Chronic heat stress, or prolonged heat stress, affects a cow’s ability to breed or stocker cattle’s ability to gain weight, Bailey explained during a recent MU Forage and Livestock Town Hall.

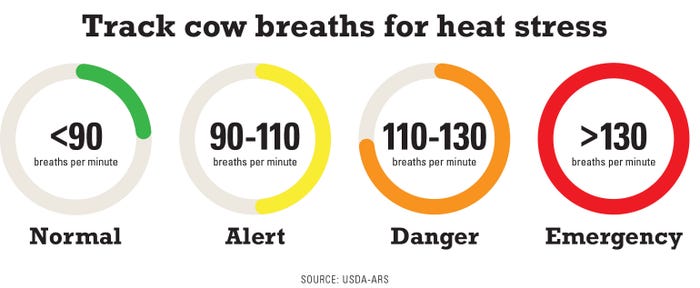

To recognize heat stress, cattle producers should watch their livestock breathe. “Cattle’s normal breathing rate is less than 90 breaths per minute, or a breath and a half per second,” Bailey said. “An animal that is breathing over 2.1 breaths per second is an animal that is likely in an emergency heat stress event.”

Risk factors of heat stress

It is not just the heat that adds to cow stress. Bailey is from New Mexico where it is common to have temperatures reach over 100 degrees F for an extended time. However, that state has nighttime cooling and low humidity levels, so livestock cool off and dissipate heat that builds during hot days.

Unfortunately, many Midwestern states have additional circumstances that exacerbate the issue. Here are some common problems:

Nighttime temperature. What concerns Bailey is when overnight temperatures remain above 70 degrees, because by nature, cattle contribute to their own heat stress.

“A mature cow has a 55-gallon fermentation batch strapped to the middle of her abdomen,” Bailey said, “and when cattle have that rumen fermentation that occurs when the microbes are breaking down the feedstuffs, that process produces heat.” The result is a reduction in feed intake.

Flies. Hot days often come with annoying flies. When cattle bunch up to reduce the amount of skin exposed to biting flies, they limit air movement around them. “Animals that are in the middle of the group receive restricted airflow and are subject to greater-than-average heat stress,” Bailey said.

High humidity. Producers should also keep humidity in mind when making decisions. Because of Missouri’s high humidity, heat stress can occur when temperatures reach the 80s.

“The thermometer does not have to scream ‘uncle’ at you before we have a severe heat stress event,” Bailey said. Cattle can adjust to elevated temperatures and humidity, but abrupt shifts in temperature and even seasonal changes can bring on heat stress.

It takes six hours for cattle to cool down after a heat stress event, he said. Cattle body temperatures peak two hours after peak daytime temperatures.

Less obvious reasons for heat stress occurring include changes in watering source or location, Bailey said.

Reducing heat stress

Here are five ways to alleviate heat stress in cattle herds:

1. Water. Allow 2-3 inches of linear head space for water for a confinement feeding operation. Bunk space for water is critical to preventing heat stress. Check water pressure to make sure tanks can keep full. Cattle drink more than 2 gallons per 100 pounds of body weight during a heat stress event.

2. Sprinklers. Use sprinklers to gently wet down animals. Avoid cold water shock. Do not mist the air to cool the animal; the mist will not get through the coat to reach the skin.

3. Water source. Make sure the cattle are familiar with the type and location of the water source. Provide adequate water and space for cattle to drink.

4. Shade. Bailey suggests looking online for shade structures to buy or build yourself. You also can move animals to natural shade areas. He recommends 20 to 40 square feet of shade per head. Shade cloth should be at least 8 feet off the ground for sufficient airflow. Orient shade either east-west or north-south. With an east-west orientation, the ground stays cooler but becomes muddy. North-south structures let shade move across the ground throughout the day.

5. Cattle handling. Don’t work cattle during high temperatures. Work in the early morning. Don’t let them stand more than 30 minutes in processing areas. Cattle in confined areas face more stress.

If there is one tip Bailey stressed, it is that a key component of reducing heat stress in cattle is water access. “I would have plans to add extra tanks or get extra water to animals if I was concerned about heat stress,” he said.

University of Missouri Extension contributed to this article.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like