Everything has its place, and when an element is misplaced, it loses its value.

For instance, healthy soil is the foundation of any crop operation. But if that soil ends up where it shouldn’t be, such as in a road’s ditch or on your house’s carpet, it becomes dirt. Likewise, a healthy plant in a row crop or pasture will provide a farmer a rich harvest or food for livestock. However, if a plant grows where it shouldn’t, it merely becomes a weed.

Same goes for hogs. Pigs raised in barns or open lots are valuable commodities for pig farmers across the country. However, herds of pigs not contained or raised for production purposes are increasing. These feral hogs are on an entirely different level than the mere nuisance of dirt on a rug or velvetleaf in a soybean field.

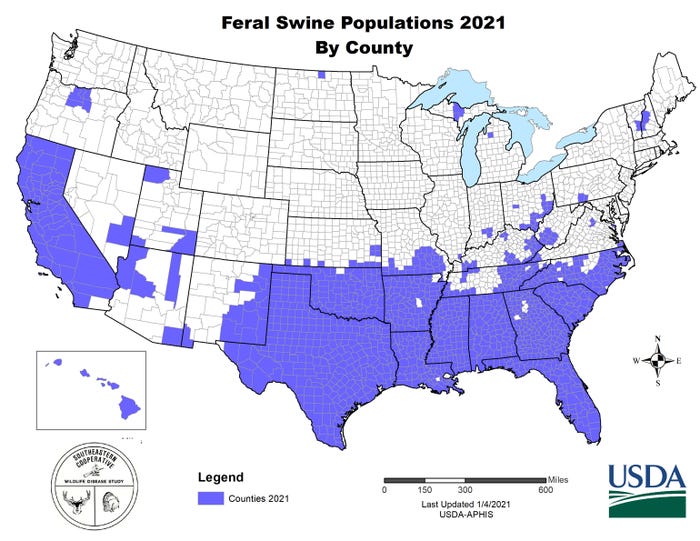

According to USDA, about 6 million feral swine roam at least 35 states. The number of feral swine is increasing, along with the damage they inflict on farm crops, estimated at $2.5 billion to U.S. agriculture annually. That’s not to mention the damage they do to private property and natural resources.

The physical damage caused by feral swine is daunting, but the harm they could do to their domestic brethren could turn the entire hog industry and the U.S. economy on its ear.

ASF risk

Various vectors are responsible for the spread of African swine fever, and among them are feral swine, or wild boars, present in the European and Asian countries where ASF is present.

ASF has yet to reach the U.S. swine herd, and we want to keep it that way. We also want to keep the feral swine population under control, if not lessened.

An Iowa State University study estimates that an ASF outbreak would costs the U.S. swine industry as much as $50 billion over 10 years. If ASF is found in the country, pork exports would come to a halt. The sooner an outbreak would be contained, the sooner the U.S. pork industry would be able to get back to business as usual. The presence of wild boars makes containment that much harder.

Having feral swine does not equate to having ASF. But should ASF reach the United States and infect a feral swine herd, the highly lethal infectious hog disease could more easily spread from the wild herd to domestic production herds.

It’s important to remember that ASF, though lethal for pigs, is not harmful to humans.

Boar hunting is big sport in some parts of the country, and it makes sense that those areas are where the feral swine population exists. Boar hunters, do your job and the U.S. hog industry will owe you a debt of gratitude.

In addition to hunters, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service created a collaborative, national feral swine damage management program in 2014 with assistance from Congress. This was before ASF started ravaging the Asian swine herd and spreading across Europe, so the importance of such a program only increases as ASF spreads.

As with any livestock disease, prevention and containment are critical. That same approach goes for the U.S. feral swine herd, which must be contained or decreased to reduce its geographic reach and potential to spread an industry-crippling disease such as ASF.

Schulz, a Farm Progress senior staff writer, grew up on the family hog farm in southern Minnesota, before a career in ag journalism, including National Hog Farmer.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like