When Bob Nielsen scouts trials in farmer fields, he uses an unmanned aerial vehicle to get a better view of what’s happening. He foresees the day when aerial scouting will deliver lots of information as data. It could even lead to new crop scouting tools that use machine learning to identify specific diseases or nutrient deficiencies.

“The biggest application today for farmers is using affordable UAVs to learn things which they can’t see from the ground,” says Nielsen, a Purdue University Extension corn specialist. “They may do it themselves or have a retailer or crops consultant do it.

“Once you find a spot in the field which doesn’t appear normal, you can use UAV imagery and GPS on your smartphone or tablet to walk to that spot and ground-truth the problem.”

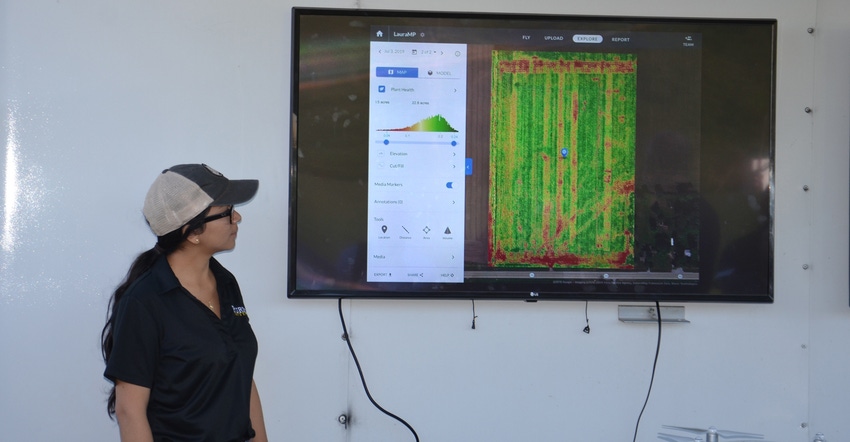

To get more information from his images, Nielsen uses DroneDeploy, a computer-based service that produces quality stitched images. He also tried Panoramic View, a new service offered by DroneDeploy in 2019.

“You program the UAV for a three-minute flight, and it goes to the center of the field,” Nielsen explains. “The camera snaps 26 images from various angles as the lens rotates into various positions.

“Once the image is stitched and I’m looking at it on my desktop, it’s almost like a 3D view. I’ve found it useful if I want a quick feel for how a field is doing.”

Future possibilities

That’s what aerial scouting can do for you today. Nielsen; Jim Camberato, Purdue Extension soil fertility specialist; and Ana Morales, a graduate student, are getting a taste of where it may be leading down the road. They occasionally scout with a more sophisticated drone with a multispectral camera. Nielsen says it can pick up five wavelengths of light. Besides red, green and blue reflectance captured by a typical camera, it also detects infrared and red-edge wavelengths.

“There are hundreds of wavelengths of light out there,” Nielsen explains. “Working with five wavelengths, we’re also getting data points rather than just pictures.”

Think of it as you would yield mapping, Nielsen suggests. “You get pretty maps, but you intuitively know there are data points with numbers behind those colors. The yield monitor collects data as numbers and turns it into colored maps. It’s similar with aerial maps. There are numbers behind the various colors which appear.”

Some researchers at the Purdue Agronomy Center for Research and Education use more intricate sensors and cameras that can detect many more wavelengths of reflected light on the higher end of the spectrum, Nielsen says. They use what’s known as hyperspectral cameras.

What turning aerial images into data and capturing many more wavelengths of light could lead to someday are sensors in cameras that could use machine learning, often called artificial intelligence, to identify specific diseases or nutrient deficiencies.

“Suppose researchers learn that gray leaf spot reflects light in a very narrow range of a specific wavelength,” Nielsen explains. “Once that’s identified, someone could likely photograph it from hundreds or thousands of positions and train a sensor to recognize it as gray leaf spot.

“We’re talking far out in the future, but that’s where aerial imaging seems to be headed,” he concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like