There’s plenty of green growing in Mike Reskovac’s wheat fields.

“I don’t grow much of this stuff, but it sure looks good,” he posted on Facebook last week.

Many farmers probably feel the same way. A mild winter and plenty of rain have been good for the region’s barley and winter wheat acres.

The most recent Crop Progress Report from USDA shows most of Pennsylvania’s barley and wheat rated either “good” or “excellent.” More than 250,000 winter wheat acres are being grown in the Keystone State.

In Ohio, where winter wheat acres tumbled 30% from last year, the crop is 51% jointed, well ahead of the five-year average of 19%. More than 420,000 acres of winter wheat are being grown.

About 11% of Michigan’s 530,000 acres of winter wheat have reached jointing, which is about average.

“Winter wheat continued to green up and was looking good across the state,” wrote Marlo D. Johnson, director of the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service Great Lakes Regional Office, in the most recent Crop Progress Report.

Maryland’s winter wheat is rated 72% “good” or “excellent.” Ratings are a little lower in Delaware, where 53% of the crop is in “fair” condition.

Reskovac grows only 10 acres of wheat. “I’m not much of a small-grain producer, but I am growing the wheat so we have some seed for planting cover crops and also straw,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean he skimps on management. The wheat was seeded last October in 15-inch rows using a Kinze bean planter. “It is knee-high on most of the field and about as deep green as it can be,” Reskovac says.

He applied a first pass of 28% nitrogen three weeks ago and applied a second pass of 28% nitrogen last week, along with 2, 4-D to control broadleaf weeds. He is also planning a fungicide pass to help control head scab.

Prepare for head scab

Speaking of head scab, also known as fusarium head blight (FHB), timing, wet weather, high humidity and higher temperatures will increase the threat of infection as the season moves along.

Scab is the most serious disease of wheat and barley, and severe cases can cause near 50% yield loss, and DON rejection or docking. Thankfully, producers have many tools, including scab-resistant varieties in wheat, that can lessen the effects of an outbreak.

Flowering, which happens three to five days after wheat starts heading, is prime time for the fusarium fungus to develop. You also need at least 85% humidity, and temperatures between 68 and 75 degrees F.

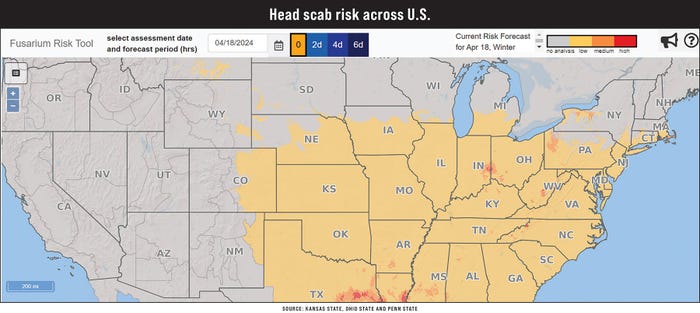

One of the best ways to assess your location’s risk for head scab is using the head scab risk assessment tool developed by researchers at Kansas State, Ohio State and Penn State. The tool uses weather and crop information to predict head scab risk up to six days out.

Currently, the risk for head scab across much of the region is low, but in areas where wheat and barley will soon be heading, and if the weather conditions are ideal, the risk will be higher.

Alyssa Collins, associate professor of plant pathology with Penn State Extension, wrote on the Fusarium Risk Tool website that barley was starting to emerge from boot in some areas of the state.

“Keep a watchful eye on your crop, and if you plan to spray for head scab, target a fungicide application for six days after the barley stems in the field have fully headed. Prosaro, Sphaerex and Miravis Ace give good control of most leaf and head diseases, in addition to suppressing scab,” she writes. “Spray nozzles should be angled at 30 degrees down from horizontal, toward the grain heads, using forward- and backward-mounted nozzles, or nozzles with a two-directional spray, such as twinjet nozzles.”

Nidhi Rawat, a small grains pathologist with University of Maryland Extension, wrote that barley is particularly susceptible to a disease outbreak because of the lack of scab-resistant varieties.

“So, if you have planted barley, keep monitoring closely for the FHB risk over the next couple of weeks,” she writes. “Remember, the best stage for applying FHB fungicides on barley is when the heads are completely out of the boots. The FHB fungicides are triazole-containing products. Do not apply strobilurin-containing fungicides.”

Rawat said some barley growers have reported stunting, yellowing and death of barley plants in their fields. The most probable cause, she writes, is freeze injury. Sudden dips in temperature after the plants caught up after winter may have led to the issue. The same issue has also been reported in neighboring states by plant pathologists.

“They also think it to be a result of cold injury,” she writes.

Here’s some more tips from Penn State Extension:

Spray timing. If you intend to protect your barley from scab using a foliar fungicide, work done by researchers in North Carolina found that the best spray timing for protecting winter barley from scab is application six days after 100% heading.

Once the crop starts heading, there is a five- to six-day window to apply a fungicide. Current labels state that the last stage of application is midflowering, and then there is a 30-day harvest restriction.

Spray products. Do not use any of the strobilurins (Quadris or Headline) or strobilurin/triazole (Twinline, Quilt or Stratego) combination products at flowering or later. There is evidence that they may cause an increase in mycotoxin production. The Miravis Ace label allows for earlier application than Caramba or Prosaro, but best results are still achieved when application is timed at heading in barley.

The Crop Protection Network, run by Cooperative Extensions around the country, has a “Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Wheat Diseases” guide. Updated last year, the guide is handy because it lists several fungicides and their efficacy against the most common barley and wheat diseases.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like