Each year, the annual Kansas Agriculture Research and Technology Association holds a winter convention to allow farmers to share what they’ve learned in on-farm research from grants supplied by the organization, and to get updates on the latest technology news from vendors and suppliers.

The annual meeting is never disappointing for those who want to stretch their imagination about what may one day be possible, and to be just a little astounded at what is already out there.

This year, at the annual meeting in Junction City from Jan. 18-19, attendees were treated to a presentation from a relatively new technology company called Blue River Technologies — a start-up acquired just months ago by John Deere.

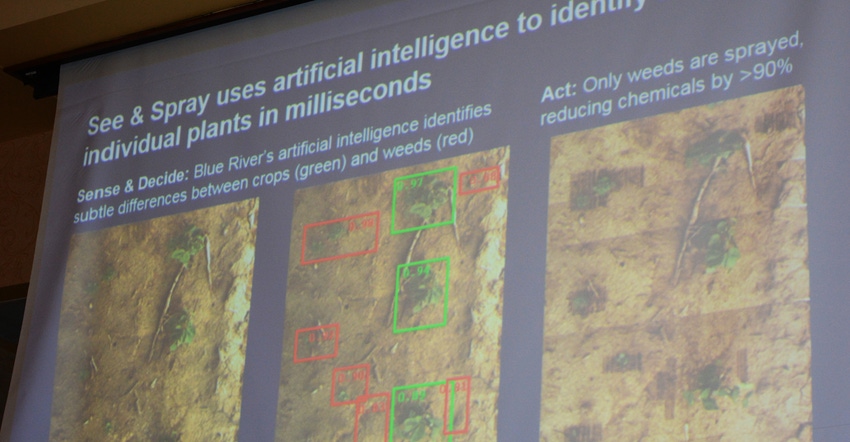

Their product is called the “See and Spray.” It’s a “smart” machine which uses artificial intelligence to handle a repetitive task in a new and novel way.

The “See and Spray” is taught — largely by repeated exposure to a variety of images — to “know” the difference between a weed, such as pigweed, and a desirable plant, such as cotton. Once the machine has this understanding, it can drive across a field at 6 mph to 8 mph, pick out the weeds and shoot them with a precision shot of herbicide.

Its biggest advantages are the huge savings in the cost of herbicide — 90% to 95% — and its advantage of not needing a herbicide tolerant crop, another huge savings in the cost of seed.

Eric Ehn, the sales person who introduced “See and Spray” at KARTA, said there have been challenges in “teaching” the machine how to accurately recognize crops and weeds in all instances. For example, he said, the machine had difficulty in a field of cotton in Texas that had sustained heavy hail damage. And, he said, it had some trouble identifying plants that were off-color or affected by disease or insect pressure and damaged.

“It essentially meant showing the machines a lot more images to get it to know sick or damaged cotton plants and correctly identify them as crop,” Ehn said. “But it was a matter of more work, not that the machine couldn’t learn the new knowledge.”

Blue River Technologies, which has a team of about 70 employees, has mostly technologists who came from the “self-driving” cars realm of artificial intelligence research. The company’s goal in AI weed control is based on a desire to drastically reduce herbicide use — lowering the amount that farmers need to spend on chemicals while at the same time cutting down the amount of herbicide that is added to the environment, Ehn said.

He added that there is potential to teach the machine to identify the seed row and zap everything not growing in the row — a technology that would allow for zapping volunteer corn or soybeans in a field of “new crop.” But, he said, it can also learn to identify in-row phenotypes and zap in-row weeds with an accuracy of as little as a quarter-inch of spacing.

“One of the things we especially have been working on is speed,” Ehn told the KARTA group. “We got up to 4 to 6 mph last year in cotton fields. Our goal is 10 mph, because that is about the speed of a typical spray rig right now. That means a farmer could precision zap just weeds in the same amount of time he now spends spraying a field. But he could do it with 10% of the amount of herbicide.”

Another advantage of the “See and Spray” system is that the nozzles of the spray rig are calibrated to shoot straight down with big droplets — no fines and, subsequently, no drift.

“Our squirt of herbicide is very local and very precise,” Ehn said. “So far, we have used a hood on the spray rig for a couple of reasons — one is to put a really precise spray shield around the application and the other is to diffuse the light on the plants and allow our cameras and sensors to get a more consistent picture of the vegetation in the row. But this year, we were able to spray Dicamba on cotton and have no damage to adjacent rows of sunflowers.”

He said that the company hopes future development will allow more “mainstream” applications of the technology to traditional spray rigs, which will also allow speeding up the process.

Ehn said that “See and Spray” isn’t really that much different than the basic artificial intelligence already out there on farm machinery. “You already have machines that sense how much down pressure is needed for a planter,” he said. “We’re advancing to look at a plant and evaluate what it is and what it needs — a desirable plant that needs a fungicide or a shot of fertilizer or micronutrients, or a weed that needs a good stiff shot of herbicide.”

Attendees at the KARTA conference were intrigued by the possibilities offered by the Blue River approach.

“It’s definitely one of the more interesting things I’ve seen lately,” said Scandia farmer Deitrich Kastens. “I want to know more.”

2017 Master Farmer Clif Heiniger said the technology cost seems likely to be offset by savings on herbicides. “I think this bears taking a closer look,” he said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like